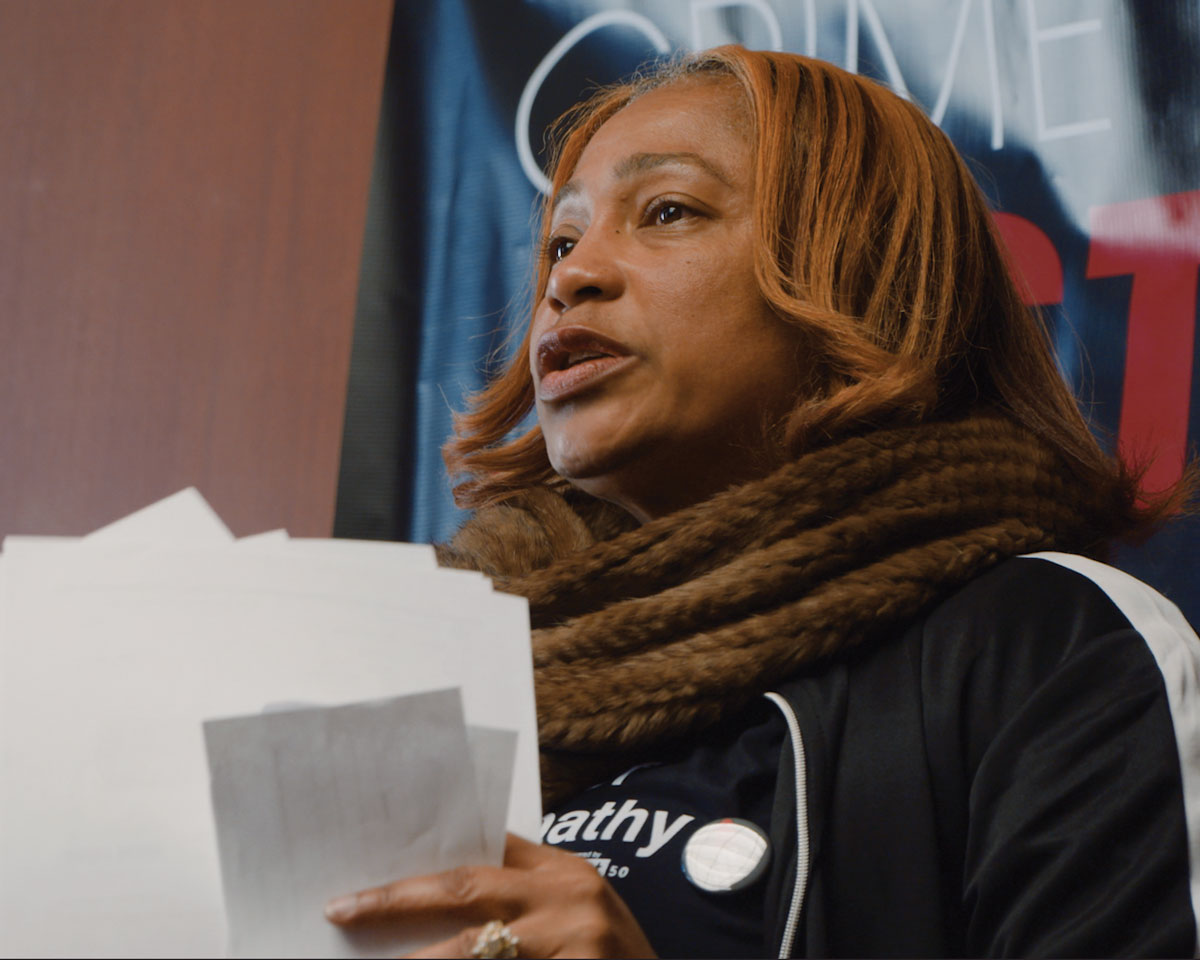

Photograph by Joseph East, Brave Voices Media

In 2017, Pamela Winn was at a drug policy–reform conference in Atlanta, preparing to help lead a discussion about the war on drugs. A budding activist for criminal-justice reform, Winn had put together a speech about her mother’s experience with substance abuse and how it affected her. Still, among the lawyers and academics, she felt uncomfortable. “I remember saying, Why do they have me on this panel?” said Winn, a mother of two and former registered nurse. “I’m not an attorney. I don’t do research.”

Then, she heard a statistic that caught her attention: Private prisons, a panelist noted, make billions of dollars each year managing the detention of incarcerated people in the United States. (In 2015, two years before Winn’s conference, the two largest private-prison companies in the country reported combined revenues around $3.5 billion.) The sentencing boom created by the war on drugs fueled the growth of for-profit detention facilities, which have been plagued by reports of neglect and abuse. Winn, though, had firsthand knowledge of the problem: Less than a decade earlier, she miscarried while in custody in a privately run facility in Georgia. “All I could think of is, these people make that kind of money, and they couldn’t do anything for me,” Winn recalled.

“I just remember getting really flushed and hot on the inside,” she said. She ditched her prepared speech and told her own story instead. It wasn’t drug-policy reform, but it painted a startling, intimate picture from inside the U.S.’s incarceration crisis. That vulnerable moment helped accelerate a growing movement, and it raised Winn’s profile as an advocate for prison reform. Her standing ovation was just the beginning.

A decade before, Winn’s life looked very different. An Atlanta native and a Grady baby, she was born to a mother who struggled with substance issues. Winn went on to earn her degree and become an OB-GYN nurse, but, in 2008, she was arrested and indicted on 20 counts of healthcare and bank fraud. During intake, she discovered she was six weeks pregnant.

Still, Winn was shackled during transport to and from court dates. “It was one thing to cuff me; it was another thing to wrap that big chain around my belly,” Winn says. “I made a mental note that I was gonna say something to the medical [staff].” She never got the chance. Climbing into a prison van that afternoon, she fell; a few days later, she started bleeding. Winn ended up miscarrying inside the detention facility, having never received—as she would later allege, in testimony before the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights—“any formal or proper prenatal care.”

After her release in 2013, Winn joined advocacy groups and connected with other formerly incarcerated women to support prison-reform bills and advocate for antishackling legislation at a national level. In 2017, following her impromptu speech, she started a petition asking Congress to pass the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act, which would prohibit shackling and solitary confinement for pregnant or postpartum incarcerated women. In just a month, the petition gained 100,000 signatures, and Winn’s efforts caught the attention of Senator Cory Booker, who invited her to Washington to participate in a roundtable. The bill didn’t pass, though some of its provisions—including a ban on shackling pregnant people in detention—were enacted as part of a separate criminal justice–reform bill signed into law in 2018. Still, the ban only covered people incarcerated in federal facilities—not the vast majority of women held in state prisons and local jails.

Winn shifted her focus to the state level—starting in Georgia, where she helped spearhead the successful bipartisan 2019 bill that prohibited the shackling of pregnant women in prisons and jails. Versions of it have since been adopted in 19 states.

She also founded RestoreHER, a policy-advocacy and reentry organization that offers comprehensive wellness, rehabilitation, and leadership programs to formerly incarcerated women. In addition to advocating for prison reform, the organization supports women who are struggling to reenter society and rebuild their lives under the burden of a criminal record. RestoreHER offers training on self-care, anger management, and restoring personal relationships; helps women find union and nontraditional jobs where their background is less important than their skill set; hosts classes with realtors who can guide women toward homeownership; provides financial literacy and investment workshops; and offers advocacy workshops that prepare women to jump into the political ring alongside Winn.

“We teach them about how a bill becomes a law, voting, how to become a legislator or lobbyist,” Winn said. “So, if they want to make change about things that they care about in their communities, they are knowledgeable of how to do those things.”

Today, Winn’s goal is to end prison birth completely. For the last two legislative sessions, she and State Representative Sharon Cooper have introduced the Georgia Women’s CARE (Childcare Alternatives, Resources, and Education) Act, which would require pregnancy testing for all arrested women within 72 hours of their detention and allow them to immediately bond out if the test is positive; it also mandates that pregnant women who are convicted and sentenced to serve time be allowed to defer their prison sentence until at least six weeks postpartum.

Progress has been steady but slow, perhaps in part because, according to Winn, people don’t readily empathize with incarcerated women. But Winn, who practiced in women’s healthcare for more than 10 years, says her advocacy is not only for the mothers: “Regardless of what you think about women, what you think about incarcerated folks, or what you think about people of color, when it comes to babies, we all agree we want safe, healthy babies.”

Learn more: Incarcerated and invisible: What happens to pregnant people in Georgia’s county jails? Read Gray Chapman’s story here.

This article appears in our March 2022 issue.