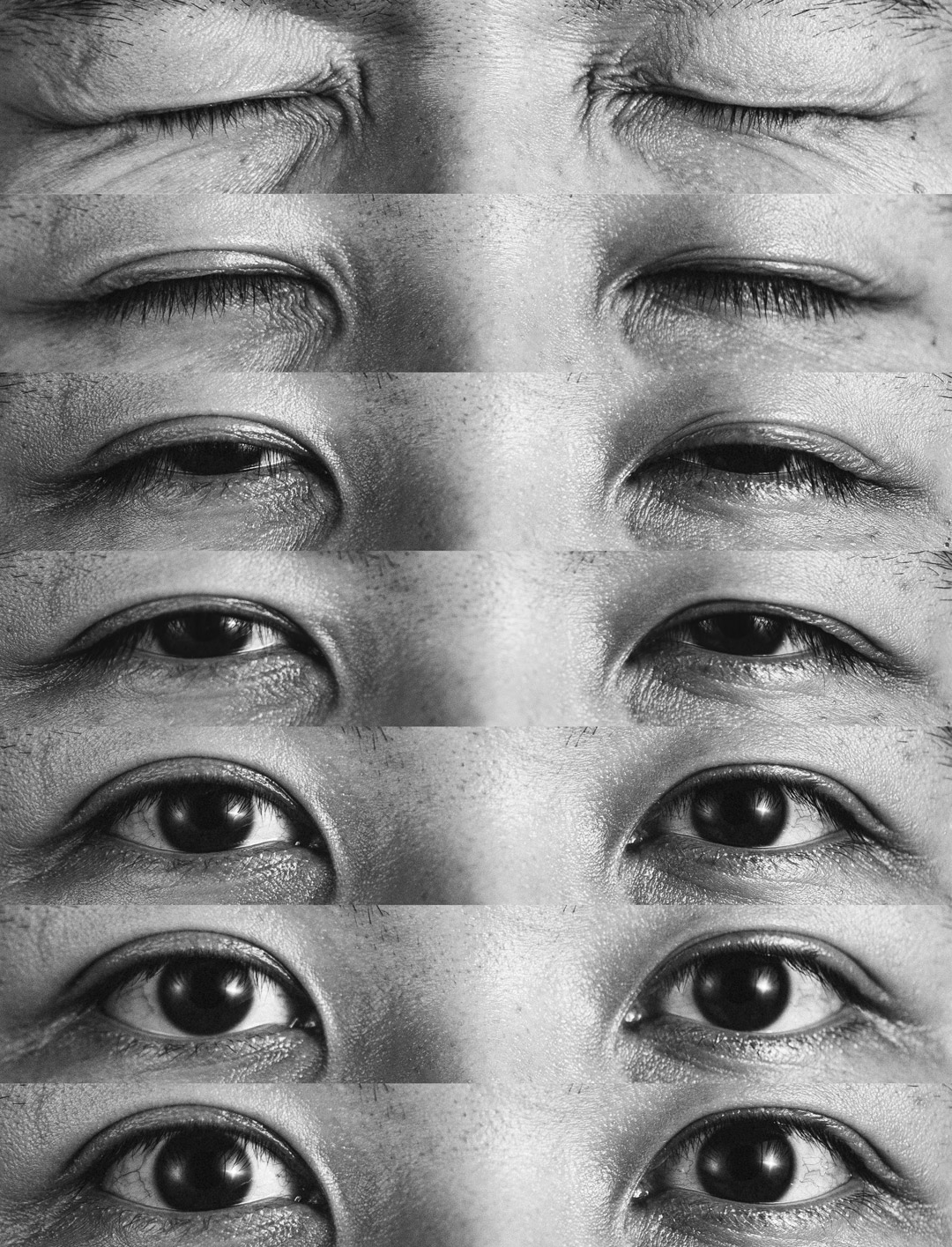

Photograph by Audra Melton

Early one Sunday morning, as Midtown’s bartenders announce last call, Son Tran listens closely to his scanner. The 27-year-old officer has just finished filing a police report—a Washington Redskins player visiting Atlanta totaled his green Corvette. Before a 911 dispatcher sends another call his way, Tran hustles into the 24-hour Chevron station on Ponce de Leon Avenue and grabs the tallest sugar-free energy drink he can find.

A Vietnamese immigrant with boyish cheeks and wire-rimmed glasses, Tran first got assigned to the Morning Watch—a rite of passage for rookie officers—in 2018. Five days a week, he clocks into APD’s CNN Center precinct just before 11 p.m. For the next eight hours, he patrols downtown and Midtown streets, doing everything from catching drunk drivers to hauling people to the Atlanta jail for disorderly conduct, public urination, or other city code violations. (Plus, untold hours of paperwork.) As months have passed, Tran has settled into a steady rhythm on the overnight shift. Except for one thing: sleep. He once slept a solid eight hours a night, back at his last job as an archive assistant. Now, he’s lucky to get five.

Photograph by Audra Melton

“The one thing I hate? That I rely so much on energy drinks,” Tran told me, sipping his Monster before speeding off to a criminal trespass call a few blocks away from Piedmont Park.

By the time we arrive, it’s three o’clock, a time at which only 3 percent of America’s workforce is, in fact, working. In Atlanta, this relatively small army of night owls—firefighters and factory workers, security guards and gas-station clerks, doctors and truck drivers—keeps the city running smoothly. Once the sun rises and the rest of us head to work, thousands of weary workers head home—or, in some cases, to yet another job. For night workers like Tran, though, that simple reversal of a work schedule can come with great sacrifice to health and lifestyle.

“We’re not designed to physically work overnight. There’s no real, ideal night-shift schedule.”

“The first few weeks, I didn’t think I could make it,” says Bill West, a 55-year-old overnight trucker. At 6 p.m., three days a week, he pulls his 18-wheeler onto Moreland Avenue, the start of a 10-hour trek to Little Rock, Arkansas. Wary of stimulants, he began by blasting AC/DC or calling other truckers on the road. As dawn approached, however, he struggled to stay alert. Over time, things got better. If he started yawning, he’d pull over for a brief nap. After his route, he embraced blackout curtains to block the sun. “I’ve never felt fully rested,” West says. “You can learn to live with it, but it’s unnatural.”

Working the night shift can feel like constant jet lag. H. Elliott Albers, director of Georgia State’s Center for Behavioral Neuroscience, says switching to nights can disrupt a tiny part of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus that controls the body’s circadian clock. In the short term, workers become disoriented or lose cognitive abilities. Chronic sleep deprivation, left untreated, can increase the risk of hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. People who work overnights can even develop Shift Work Sleep Disorder, a chronic condition recognized by the National Sleep Foundation that is linked to cancer, depression, and even premature death.

Once an overnight nurse, Ann E. Rogers has spent her career researching the effects of insufficient sleep in the workplace. She says night-shift workers are more prone to occupational injuries—from drivers falling asleep at the wheel to nurses sticking themselves with needles. “We’re not designed to physically work overnight,” says Rogers, now a nursing professor at Emory University. “There’s no real, ideal night-shift schedule.”

“I’ve never felt fully rested. You can learn to live with it, but it’s unnatural.”

While some employers have found workarounds—medical providers in Perth, Australia, 12 hours ahead of Atlanta, now see some Emory ICU patients via teleconferencing software and equipment—cities can’t function without the night shift. It’s that very shift that allows places like Atlanta, that strive to be 24/7 cities, to never sleep. Talk to night-shift workers, and you’ll hear a wide range of tactics for both staying up on shift and getting to sleep afterward. Rogers, for her part, suggests midshift naps. Tran’s secret: a $4,000 mattress that has 10,000 microsprings.

“Melatonin can get you back on track,” says Dr. Michael Lacey, a medical director of the Atlanta School of Sleep Medicine. “We also use light boxes”—patients sit next to a lightbulb-filled rectangular fixture at home after they wake up, which he says stimulates an area deep in the brain to trigger dopamine—“to lessen the shock of night shifts on the body.”

The best way to adapt to the night shift? Stick to the schedule, even on off-days, according to Albers. That’s easier said than done. Three years ago, when I worked as an overnight news writer for CNN, my work week started Saturdays at 10:30 p.m. and ended Thursdays at 6:30 a.m. I tried shifting my sleep schedule to call my parents, run errands, and maintain a social life. I tried everything from a sleeping mask to earplugs to melatonin. But none of that could offset my erratic sleeping pattern. Soon, I grew unhappy, ate poorly, and felt fatigued. I quit after five months.

Photograph by Audra Melton

Not everyone can do the same. That’s the case for Tran, who’ll work nights for the foreseeable future. Later that Sunday, not long after the sun rises, Tran heads from the CNN Center to his home in Morrow. He chats with his wife about his shift and decompresses by watching funny YouTube videos. An hour later, he closes the blinds, dons his sleeping mask, and shuts his eyes on his dream mattress. Another Morning Watch is fast approaching.

This article appears in our September 2019 issue.