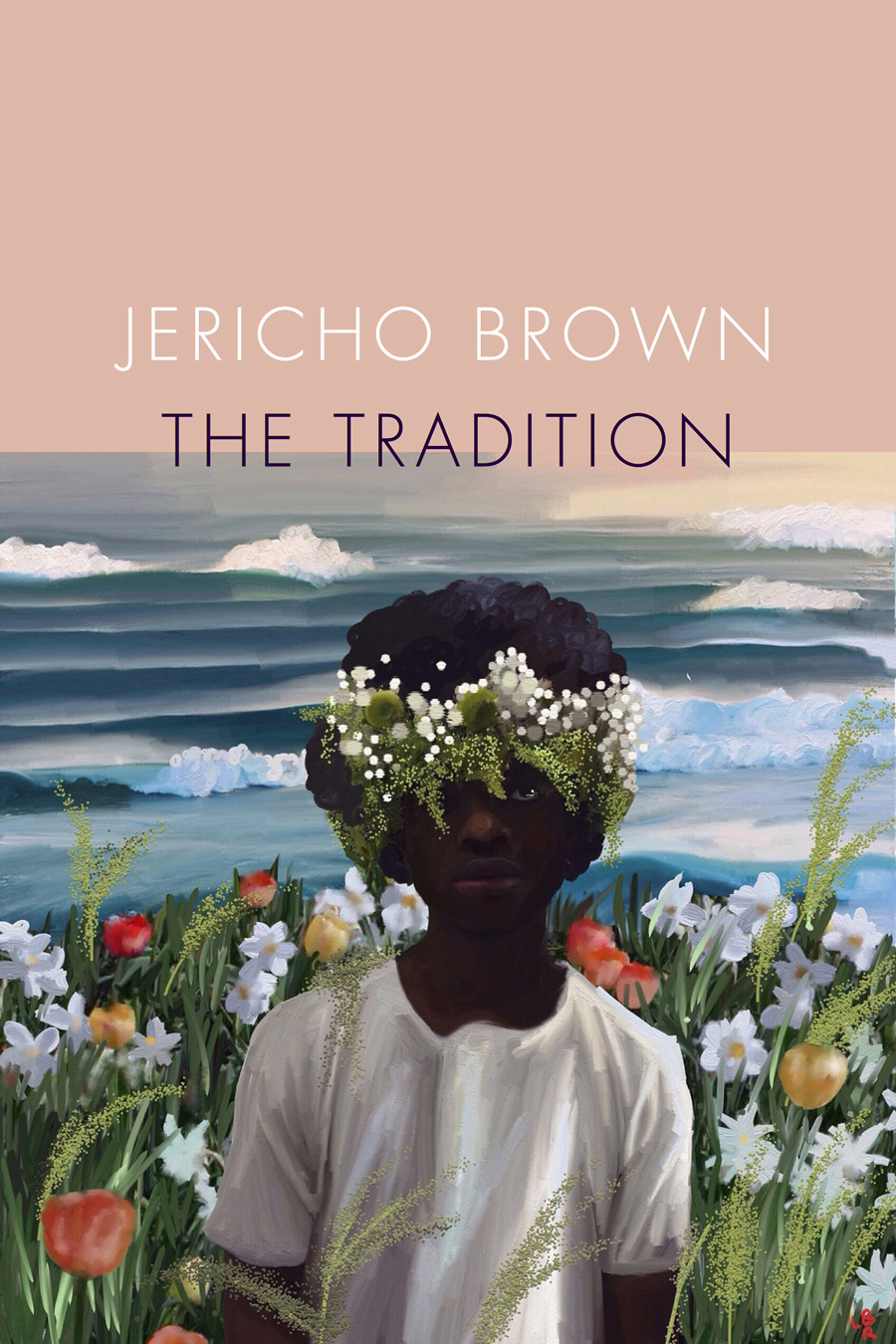

Photograph courtesy of Copper Canyon Books

In Jericho Brown’s stirring poem “The Virus,” he writes:

I want you

To heed that I’m still here

Just beneath your skin and in

Each organ

The way anger dwells in a man

Who studies the history of his nation.

If I can’t leave you

Dead, I’ll have

You vexed.

The title and sentiment feel especially poignant as the world faces a pandemic and Georgia is making national headlines for the killing of an unarmed black man, Ahmaud Arbery. This collision of beauty and disaster while grappling with racism is exemplary of the poems in Brown’s book, The Tradition. Released in April 2019, The Tradition is divided into three parts: The first part utilizes Greek mythology to reflect on nature and race; the second part on labor and race; and the third on the entanglement of violence, race, and love. It’s the third book by the Louisiana native, who directs the Creative Writing program at Emory University. The resonance of “The Virus” and other pieces in the book, is just what he intended—a reflection on the ills that have been committed by and against America.

Photograph courtesy of Copper Canyon Press

On Monday, Brown was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for The Tradition, and he has been moving nonstop ever since. When we spoke on the phone, he had just woken up from a much-needed nap and was still processing what it meant to see a dream he’s had since he was eight-years-old come true.

You weren’t born Jericho Brown. Why did you decide to change your name?

I was born Nelson Demery III, and it was an exciting name to have when I was a kid because it felt kind of grand. As I got older, it was a name that meant that I was walking around in other people’s shoes, and I wanted to walk around in my own shoes, especially after I started getting poems published. I love my dad so much, but we always had this really contentious relationship when I was growing up. I remember looking at a poem the first time it came out and looking at the name Nelson Demery III, and thinking ‘wow, I don’t even get this to be mine.’ I changed my name because I wanted to put my own stamp on my own work.

I used to put mustard on my sandwiches until I was in my 20s because my dad put mustard on his sandwiches, and I don’t even like mustard. One of the things I wanted to do in this book to see how many things we take for granted and act as if are normal and they’re not okay. If you don’t like mustard, you can take it off your sandwich, but there are other things that are much larger and much more serious, that we claim not to like, but they’re still a part of our lives.

What inspired you to write The Tradition?

There are three answers to that question. When I first moved into my house, I was working on a flower bed in front of my porch. My neighbors did this thing I had never experienced where they would come and say hi and bring food. I was working on a flower bed, and one of my neighbors rang the doorbell and said she was looking for the man or the woman of the house. I announced that it was me, and I realized that she could imagine me doing the work to take care of these flowers, but couldn’t imagine that they were my flowers.

At the same time, we were seeing these images of unarmed black people being murdered by police for no reason. I was brokenhearted about all of them, but especially Tamir Rice. I don’t know what made me watch that video over and over, but that’s the one that sent me to the page. Everybody in this country knows we have a problem with policing or that relates to race. But that knowledge doesn’t reconcile us to one another.

Another thing I was writing about is assault. I am always writing about Greek myths, [which contain] a lot of rape. The titles are often called “The rape of . . .” or “The assault of . . .” and these stories are handed to us as if it’s the normal trouble. We say someone got raped as if there was no agency. It’s not something that I wanted to write about, but once I got started, I realized that it’s something that needed to be a part of the book.

In the poem “The Tradition,” you compare black men slain by police to perennials. You mentioned Tamir Rice earlier. Does each instance of hearing about black men killed by police feel like the end of a world for you?

Some of our earliest images of this have to do with postcards that were made during lynchings. In a more contemporary sense, we have Rodney King’s beating, which black people had to watch on television with a knowledge of just how regularly something like that could happen. It’s not that it feels apocalyptic to me. It puts me in a position where I cringe to think that the apocalyptic world is worse than that.

Tell me what are you working on now? What’s next for you?

I’m working on essays about my life, poetry, and about our culture, our society. I have a lot of essays that have been published in different magazines and I’m compiling them into a book that will be part memoir and part criticism.

Who are your favorite poets and writers?

Today, I am feeling most inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks, Yusef Komunyakaa, Natasha Trethewey, Tracy K. Smith, Gregory Pardlo, Tyehimba Jess, and Rita Dove. This is the 70th anniversary of Brooks’ win of the Pulitzer Prize, which means it’s the 70th anniversary of the first time a black person won. It’s hard for me to say without getting emotional. I feel like she’s with me and that I’m walking in her footsteps. All the poets I named are all the black poets who’ve ever won the Pulitzer Prize. There are eight of us now in the 103-year history of the prize, and I’m just happy to be part of that number.