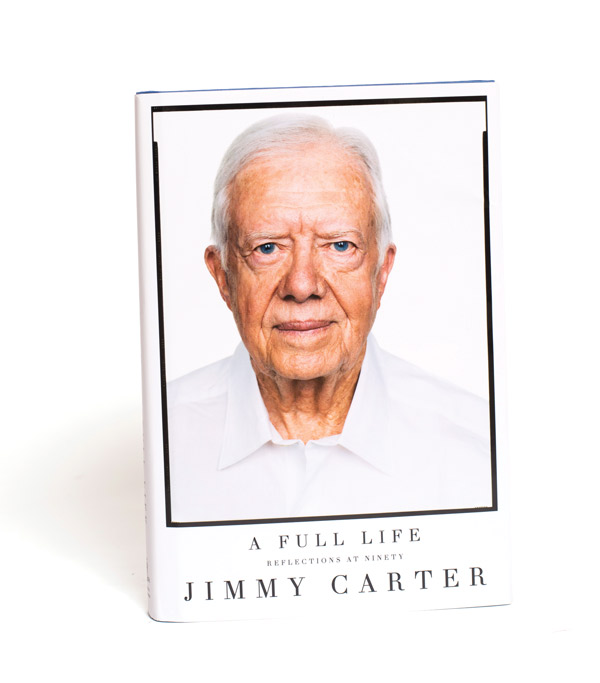

Photograph courtesy of Simon & Schuster

Although my father had served in the state legislature and our family members were loyal Democrats and publicly supported local and state candidates, I had never had any interest in seeking public office and took no part in politics except to join my mother—and most Georgians—in supporting Adlai Stevenson and John Kennedy. I decided to run for office in 1962, after the Supreme Court ruled in Baker v. Carr that all votes had to be weighted as equally as possible. This resulted in the termination of Georgia’s “county unit” system, where some rural votes equaled 100 votes in urban areas. As part of the state’s response, seats in the Georgia Senate that had rotated every two years were replaced by permanent ones, with much more power and prestige. I decided, somewhat quixotically, to help save the state’s public school system—threatened with closure if it was racially integrated—by becoming a Senate candidate. I was changing from my khaki work clothes into a coat and tie when Rosalynn asked if I was going to a funeral. It seems inconceivable to me now, but I had not consulted her about my plans, and replied that I was going to the courthouse to qualify as a senatorial candidate and to place an announcement in the local newspaper. Rosalynn was pleased and excited by my decision, which she did not question.

The general presumption was that candidates elected under the old system would be chosen, so only 10 days were allowed for campaigning before the special election. Our new Senate district comprised seven counties, with a total population of about 75,000. I had some posters and calling cards printed and began to go from one county seat to another, visiting the newspaper offices and radio stations in the area and speaking to any civic club that would accept my request. It was during a slack time of year for farming, and Rosalynn and my brother, Billy, ran the office while I was away.

We were having a one-week revival at our church, and the visiting pastor was staying with my mother. When I stopped by to tell her of my plans, the preacher asked, “Why in the world would you want to become involved in the dirty game of politics?” After thinking for a few moments, I responded, “How would you like to be pastor of a church with 75,000 members?”

My opponent was Homer Moore, a warehouseman and peanut buyer from my mother’s hometown whom I knew and respected as an honest business competitor. Each of us had a natural advantage in our home community, and I already knew a lot of farmers and Lions Club members. Another key factor that helped me overcome my late decision was that members of our square dancing group came from most of the same area that the senatorial district covered, and they gave me strong support.

On Election Day I was rushing from one polling place to another when I called in to Rosalynn and she informed me that a cousin of hers had reported a serious problem in Georgetown, the county seat of Quitman County, one of the smallest in Georgia. We asked John Pope, a friend of ours, to go to the courthouse to represent me. When he arrived he was dismayed to see the local political boss, Joe Hurst, ostentatiously helping my opponent. He was requiring all voters to mark their ballots on a table in front of him and telling them to vote for Homer Moore. The ballots were then dropped through a large hole in a pasteboard box, and John watched Hurst reach into the box several times, remove some ballots, and discard them.

I called the newspaper in Columbus, Georgia, the largest city in Southwest Georgia, and told their political reporter what was happening. His name was Luke Teasley, and he had interviewed me after I became a candidate. I drove to Georgetown. Hurst did not seem disturbed that he was being observed, even when I demanded that he cease his illegal tampering with the election. He responded only that this was his county, he was chairman of the Quitman County Democratic Party, and this was the way elections were always conducted. As the candidate, I was free to talk to his friend the sheriff if I had a legal complaint to register. After Hurst discounted my complaints, Teasley arrived in Georgetown, and his attitude was primarily amusement that “Old Joe” was still up to his normal tricks. John Pope stayed there and recorded what was happening during the day, and I left to visit the other counties.

I was ahead by 75 votes when the returns were received from the other six counties, but in Quitman County the vote was 360 to 136 for my opponent, although only 333 people had voted. Homer Moore was declared to be elected by the news media. The state Democratic Convention was meeting in Macon that same week, and I went there to register my complaint, which was ignored. Even some of my closest friends thought I was just a sore loser and advised me to drop the issue and decide if I wanted to run in two years. I heard my mother say to my sister, “Jimmy is so naive, so naive.” If I had understood the strange election laws, I may have withdrawn, but I was angry. I had envisioned the recent Supreme Court rulings to be opening a new era in Georgia, based on the value of individual votes instead of votes by county, and perhaps involving a new group of legislators who could ease the way toward racial conciliation.

I went to the law office of Warren Fortson, the county attorney, and he and I examined the statutes relating to contested elections. They were almost exclusively devoted to a mathematical recount of ballots and not to fraud. In such a rare case, the appeal should be made within five days to the county Democratic Committee, of which Joe Hurst was chairman and had handpicked all the members. Our only recourse was to present the necessary appeal and then file for a recount, which would be conducted by a regional trial judge. We had a meeting in the home of my first cousin Hugh Carter, and he suggested we call his older brother, Don, who had been city editor of the Atlanta Journal. The newspaper soon assigned a skeptical reporter, John Pennington, to the story, and he came by to see me, then went to Georgetown, where he had a highly publicized confrontation with Joe Hurst. A series of vivid front-page articles swept the state.

Pennington learned that 117 voters had allegedly lined up in exact alphabetical order to cast their ballots. Many were dead, in prison, or living in distant places. Cartoons in the Journal showed graveyard voting precincts with caskets open while their inhabitants exercised their rights as citizens. We found many Quitman County residents willing to confront Hurst, and we worked day and night to accumulate a stack of sworn affidavits confirming our case. The county courthouse was packed when we appeared before the Democratic Executive Committee, but the first order of business was a motion made by my opponent’s attorney that the charges be rejected, and Hurst and his committee voted unanimously to agree with the motion. No evidence was accepted. This left us with the possibility of a simple recount of ballots that were cast, and a conservative judge, Carl Crow, was designated to preside.

Since Fortson was known to be my personal friend and was quite liberal on the racial issue, he decided not to represent me at this hearing. Instead, he introduced me to Charles Kirbo, originally from South Georgia but now practicing in the large Atlanta firm of King & Spalding, and he agreed to take my case. All we knew in advance was that a total of 496 votes had been reported (360–136) but only 333 people had cast a ballot when the polls closed. Even Joe Hurst had stated that there were no absentee ballots. Those who had conducted the election all stated that no voters had been influenced during the day, everything had been done properly, and all the ballots, stubs, and voters’ lists were in the box. The big question was, Where was the box and what was in it?

When the cardboard container was finally found (under the bed of Joe Hurst’s daughter) and placed on the table, it was seen that the flaps were unsealed and that no documents were there—only a pile of ballots. More than 100 were rolled up together on top and encircled by a rubber band. In a lengthy statement, speaking slowly and with long pauses, Kirbo described what had been revealed and compared the situation to an account of a chicken thief who dragged a broom behind him to conceal his tracks from the sheriff. With no ballot stubs or voters’ lists, Hurst had left no way to determine how many ballots should be in the box. The opposing attorneys decided not to respond, and Judge Crow adjourned the session without comment, except that he would announce his decision the next Friday, November 2, in Albany. The Columbus newspaper reported on page 13 that “Jerry Carter from Plains, who lost to Homer Moore,” would lose a recount petition.

On Friday, Judge Crow described the disparity in votes cast in Georgetown, stated that there had been no voting booths and no secret ballot, and that there was no way to determine the result of the election. All the Georgetown ballots were nullified, and the three small county precincts had voted 43 for Moore and 33 for me. This made the district total 2,811 to 2,746, in my favor. If implemented, his decision meant that I was the nominee of the Democratic Party, with no Republican opposition! We all pledged to drink only Old Crow whiskey in the future.

The state party and secretary of state ruled that my name should be on the general election ballot the following Tuesday, but Homer Moore appealed to our local superior court judge, Tom Marshall, and he ruled late Monday night that names should be stricken from all the ballots and that the election be decided solely by new votes to be cast throughout the district the following day—beginning in about six hours. I hadn’t been to bed for several days and had lost 11 pounds, but I continued to campaign during election day as much as possible. Two county ordinaries did not remove all names as directed, and in most counties the result was similar to the first one. In Quitman County, however, the voters felt for the first time in many years that they were free from oppression, and there were 448 to 23 votes in my favor. The overall tally in the district was 3,013 to 2,182.

Homer decided to appeal directly to the members of the Georgia Senate, whose presiding officer was Lieutenant Governor Peter Zack Geer, a close friend of Homer and Joe Hurst who had always carried Quitman County by 10-to-1 margins. There was another contested election in Savannah, Georgia, and the lieutenant governor refused to discuss either one before the legislature convened. We knew that he had absolute control over the Senate and would be assigning the newly elected members to committees and other posts. In effect, Peter Zack would decide between Homer and me. The issue was still very much in doubt.

I notified my fellow school board members that I would resign as chairman if elected, and would concentrate on educational matters as a senator. After sleeping for a full day, I began studying the Senate rules and procedures and other issues of importance in the district. I went to Atlanta in late November to meet the lieutenant governor, and Peter Zack received me politely. He said he couldn’t discuss any possible contest, noted that I was about the last one to come to see him, and asked for my committee preference. Homer Moore had already made his requests. I said my only preference was the education committee, and he was surprised that I didn’t ask for rules, appropriations, judiciary, or industry and trade. He said there should be no problem. The top positions were filled, but if I liked to write, he might make me secretary. I accepted and started to leave, then asked if there was a subcommittee on the university system. There was not, and I asked if one could be formed. He called the upcoming committee chairman, who had no objection to my being head of the new subcommittee on higher education—if I should be a senator.

It is the custom in Georgia to have a wild hog supper the night before the legislature convenes, and Rosalynn and I went to the affair in the old Biltmore Hotel in Atlanta. As we approached Peter Zack’s suite, we met Homer Moore and his attorneys leaving, with broad smiles on their faces. We hoped that the lieutenant governor had just told a joke. The next day we were nervous and discouraged when the Senate was called to order, but I was sworn in without question. I was also on the agriculture committee and, after a few weeks, on appropriations. I worked hard, read all the bills, and enjoyed the few weeks each year when we were in session. I wrote a book later called Turning Point to describe this entire event, which was my introduction to politics. I had learned a lot in just a few weeks.

My two personal legislative goals were to improve election procedures and to secure a four-year college in Southwest Georgia. Now, having a lot of experience on the voting issue, I worked with a small group of lawyers from the judiciary committee to draft a comprehensive reform package that incorporated effects of recent Supreme Court decisions and clarified procedures to be followed in cases of fraud. I remember that one floor amendment was proposed by a senator from Enigma (I envied his hometown’s name) that would “prohibit any citizen from casting a ballot in a primary or general election who has been dead more than three years.” A good-spirited debate included claims that wives or children could decide fairly accurately how their deceased loved one would still vote after such a brief time. The reforms were overwhelmingly approved, without the proposed amendment.

The other issue was much more important in my district, because the nearest senior college was Auburn University in Alabama, where our students had to pay out-of-state fees. The two junior colleges eligible for promotion were Georgia Southwestern in Americus (my county seat) and a larger institution in Columbus. The elected governor, Carl Sanders, had promised the people of Americus that he would support their request but had backed down under pressure from Columbus. Their supporter, Bo Callaway, was our district representative on the Board of Regents. He was wealthy, politically influential, and chairman of the committee that decided on the academic status of all colleges. I was at a great disadvantage, except that I was chairman of the subcommittee that would have to approve any funding for the university system. The governor wanted a new dental school in his hometown, and I had the proposed legislation in my pocket. Following some quiet but intense negotiations between me and the governor, he used his influence among the regents, the dental school was funded, and Georgia Southwestern became a senior college. Primarily because of this achievement, I was reelected in 1964 without opposition for another two-year term. But it left some bad feelings between me and Callaway.

From the book A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety by Jimmy Carter. Copyright © 2015 by Jimmy Carter. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster.

This article originally appeared in our August 2015 issue.