Long before a mouse named Mickey showed up in central Florida, the South was dotted with roadside attractions and family-owned amusements. Rock formations, natural springs, botanical gardens, and menageries of animals were the mainstays of vacation fun. And while some of these beloved spots live on only in memory, many continue to welcome visitors—and have even experienced a recent surge in interest and attendance. So come along as we pay a visit to some of the region’s most legendary and long-standing attractions.

Photograph courtesy of Rock City

Rock City

Lookout Mountain, Georgia

Real estate developer Garnet Carter hit it big as the creator of the nation’s first miniature golf course in 1928. Set atop Lookout Mountain, Georgia, it was part of his planned community, Fairyland—the name a nod to his wife Frieda’s love of European folklore. The game caught on, and he franchised the concept nationwide as Tom Thumb Golf. But as the Depression spread gloom across the country, the venture foundered, and Carter began casting about for a new business opportunity. He didn’t have to look far: Frieda had begun planting a rock garden to end all rock gardens on a portion of their development known as Rock City. At this natural collection of massive boulders, the stones are set in such a way as to create streets and alleys in between them.

Photograph courtesy of Rock City

Using string, Frieda had marked a trail that wound through the rock formations and ended at an outcropping known as Lover’s Leap, which offered stunning views of the countryside and glimpses of seven states. She’d planted wildflowers and other plants along the path and populated it with German statues of gnomes and other fairytale characters. In May 1932, the Carters opened Rock City Gardens to the paying public.

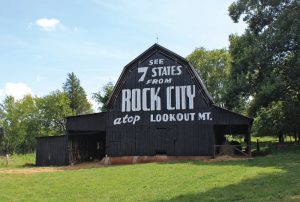

But the anticipated crowds failed to appear. Trouble was, unlike the popular roadside attractions of the day, Rock City’s mountaintop location failed to catch the attention of travelers. So Carter hatched a plan to get the word out. In 1936, he hired a young artist, Clark Byers, to travel the nation and paint three words—See Rock City—on the barns of willing farmers. (In exchange, he painted the rest of the barn for free.) The idea worked, and vacationers began ascending Lookout Mountain in droves.

Photograph courtesy of Rock City

In 1947, with the Baby Boom underway, the Carters looked to add some child-friendly appeal. They put a roof over one of the rock crevices and filled the resulting cave with glowing sculptures of Little Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Fairyland Caverns was such a hit, Rock City opened a similar fairytale-themed attraction, Mother Goose Village, in 1964.

In the ensuing decades, shops and restaurants were added to the park, but few changes were made to Frieda’s path. In fact, to this day, Rock City’s original layout remains almost entirely intact. From Fat Man’s Squeeze, a narrow fissure along the trail through which guests hold their breath and pass, to the colorful gnomes one encounters along the way, the elements that first wowed guests more than eight decades ago continue to delight those who heed the call to see Rock City. —K.B.

Photograph courtesy of Fountain of Youth

The Fountain of Youth

St. Augustine, Florida

A woman turns to her friend after taking a swig of water from what looks like an oversized shot glass. “Do I look younger?” she asks. Both women laugh. The drink might not have done the trick, but their smiles do.

Welcome to Ponce de Leon’s Fountain of Youth Archeological Park, which promises eternal youth—or at least the dream of it. Today’s drinkers are the latest in a long string of hopefuls, supposedly starting with Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon. Legend holds that he was searching for the Fountain of Youth when he arrived in present-day St. Augustine in 1513, lured by rumors of a nearby spring with waters that erased the effects of aging.

Photograph courtesy of Fountain of Youth

Visitors to the park can see purported evidence of Ponce de Leon’s visit to the area, including a coquina cross fifteen stones high and thirteen stones across on display next to the fountain. A small silver container, also on display, is a replica of one that held an affidavit stating that Ponce de Leon made the cross to commemorate the year of his arrival, 1513.

(Quick side note: The historical accuracy of Ponce de Leon’s search for the Fountain of Youth has eroded over the years. There is, in fact, little evidence to suggest he set out to find such a mythical fount. No matter. The legend lives on, as does the spring.)

In the late nineteenth century, the Fountain of Youth became a bona fide attraction. In fact, its guest books date to 1868, making it Florida’s oldest tourist destination. In 1900, owner Henry H. Williams sold it to Luella Day McConnell, aka Diamond Lil, who aggressively promoted “Ponce’s Famous Spring!” After she passed in 1927, the park was sold to state senator Walter B. Fraser and has remained in his family ever since.

Photograph courtesy of Fountain of Youth

Over the decades, the Frasers have worked to turn the property into a manicured waterfront park filled with peacocks and plenty of exhibits on Florida’s early history. Visitors can explore a recreation of a Timucuan village, which shows what Native American life was like here before the arrival of the Spanish. They can also see a statue of Pedro Menendez, who established the first successful European settlement in North America at St. Augustine, exactly where the park is now. There’s a replica of a mission church, a blacksmith shop, and a Spanish watchtower. There’s even a planetarium that explains how explorers used the stars to navigate the sea. But the main attraction at the Fountain of Youth is—and will likely always be—the spring and its supposedly miraculous water. (Small cups are provided, but you may bring your own containers, too, if you suspect it might take more than a sip to do the trick.) True, it might not help us live forever, but it’s a good reminder to make the most of the time we have left. —D.F.

Photograph courtesy of Chimney Rock

Chimney Rock

Western North Carolina

Before May 1949, the trek to the top of granite monolith Chimney Rock was a calf-burning pilgrimage. After following a staircase up 1,965 feet, visitors would have to climb a system of stairs and ladders 315 feet higher to reach the peak of an outcropping. If the day was clear, they’d be rewarded with panoramic views of the western North Carolina countryside and Hickory Nut Gorge. Then came the modern era. In 1947, eight tons of dynamite and eighteen months of hard labor bore an elevator shaft into a nearby cliff, thereby transforming the Chimney into one of the South’s most accessible sky-high destinations.

Photograph courtesy of Chimney Rock

If the elevator’s twenty-six-story ascent transcends the vision of Chimney Rock’s early proprietors, then it isn’t by much—all puns aside, farsightedness has always been a driver of the Chimney’s success. The first stairs to the peak were built by owner Jerome Freeman, who’d bought the Chimney and its surrounding acres from a speculation company in the 1890s; however, Freeman’s successor, Dr. Lucius Morse, was the attraction’s true visionary. A former physician, Morse had moved to the mountains after being diagnosed with tuberculosis. To take in the area’s healthful climate, he often rode on horseback through the valley, admiring the Chimney from below. Morse eventually paid a man twenty-five cents to take him by donkey to the peak. There, atop the “Land of the Sky,” he conceived the idea for a sprawling park, a dam and lake, and a year-round resort town. In 1902, with help from his brothers, he bought the sixty-four-acre Chimney Rock Mountain for $5,000.

In the years that followed, the Morse family would continue to shepherd the park’s growth, expanding its footprint to 1,000 acres and adding paved roads and trails. The town of Lake Lure, which was named by Morse’s wife, was incorporated in 1927.

Photograph courtesy of visitnc.com

The ensuing decades brought more visitors and acclaim to the bustling valley. Beyond the Chimney itself, park-goers sought attractions like the 404-foot-tall Hickory Nut Falls (featured in the 1992 film The Last of the Mohicans), impressive views from the park’s aptly named Opera Box overlook, and abundant hiking. In the midst of stock car racing’s early heyday, there was even a two-mile road race that slung drivers around the mountain’s hairpin turns. The Chimney Rock Hillclimb, as it was called, was a beloved local tradition for almost forty years.

What kept people coming back year after year, though, was the view from the top of the 535-million-year-old granite landmark. When the historic elevator closed in 2012 for renovations, floods of visitors still braved the attraction’s 499 steps to share in one of the South’s natural wonders.

Photograph courtesy of Chimney Rock

Today Chimney Rock, a state park since 2007, spans 5,700 acres and has six trails, including the park’s newest addition, the Skyline Trail, which opened in September 2017 and leads to the upper cascades of Hickory Nut Falls. Rock climbers, stair-running fitness fanatics, leaf peepers, even newlyweds—yes, you can get married on top of Chimney Rock—make up the 250,000 visitors the park sees each year.

As for the elevator? It reopened in 2018 and lifts visitors to the peak in just thirty-two seconds. Although it’s not the same one from the 1940s, it’s still a straight shot to the heavens. —B.C.

Photograph courtesy of Weeki Wachee Springs

Weeki Wachee Springs

West central Florida

Alongside U.S. 19 in west central Florida, about an hour north of Tampa, visitors descend into a concrete bunker set on a cerulean spring-fed pool. They’re not here to spy on alligators or manatees; they’ve come to see something altogether different, creatures more fabulous and rare. Since October 1947, when the first show opened at the Weeki Wachee Springs underwater theater, this natural spring—the deepest in the United States—has been the home of mermaids.

Navy frogman Newton Perry was the theater’s mastermind. After returning home from World War II, he was looking for a business opportunity. When he came upon a spring at the head of a river the Seminole Indians called Weeki Wachee (meaning “little spring” or “winding river”), he bought it, clearing the rusted appliances and wrecked cars that had been abandoned there over the decades. He perfected an underwater breathing method that allowed swimmers to take in oxygen from an air hose connected to a compressor. He then went in search of attractive local girls, who would become the park’s first mermaids.

Photograph courtesy of Weeki Wachee Springs

In the early days, swimmers wore one-piece bathing suits and performed aquatic ballets or enjoyed underwater picnics, eating fruit and drinking bottled sodas while turtles and fish swam by. In 1959, the small roadside attraction made it to the big leagues: ABC purchased the park, replaced Perry’s fifty-seat theater with the current 400-seat one, and began producing elaborate circus- and pirate-themed shows, as well as underwater adaptations of classics such as The Wizard of Oz and Snow White.

Photograph courtesy of Weeki Wachee Springs

The crowds went wild. In the 1960s, more attractions were added to satisfy their curiosity, including glass-bottomed boats, a jungle cruise with live animals, and a tram ride to a recreated Native American camp touted as “Florida’s only authentic Seminole Indian ghost village.” Promotional literature with endorsements from the likes of Roy Rogers, Bob Hope, and even rocket scientist Wernher von Braun flooded the country. Elvis Presley visited the park. And the mermaids became international stars, with young women arriving from as far as Tokyo to audition for the coveted roles.

In the years following the 1971 opening of Walt Disney World, Weeki Wachee Springs, like many Florida roadside attractions, struggled to tread water. But the park held on, and in 2008 it became a Florida state park. In recent years, it’s seen a surge in attendance (from 151,000 guests in 2010 to almost 400,000 last year—a whopping 165 percent increase), thanks in part to the current pop culture obsession with mythical creatures. In addition to the mermaid shows—which include patriotic performances set to Lee Greenwood’s God Bless the USA and an adaptation of (what else?) The Little Mermaid—visitors may take in wildlife demonstrations or board a pontoon boat for a twenty-five-minute cruise on the Weeki Wachee River. And should any guests find it impossible to resist the siren call to don a Lycra tail and take the plunge, the park also offers weekend mermaid camps, where participants learn underwater ballet moves and get behind-the-scenes access to the show. —K.B.

Photograph courtesy of the Lost Sea

The Lost Sea

Sweetwater, Tennessee

Many have attempted to explore the depths and distance of the Lost Sea, an underground lake within Craighead Caverns, but to little avail. Divers in the seventies found several water-filled rooms deep below the surface, but the conditions were too dangerous for them to explore further. The full extent of the Lost Sea—the largest underground lake in the country and the second largest in the world—remains, well, lost to mankind.

Thanks to fossils, we do know a few things about the history of the caverns: Its earliest known inhabitant was a Pleistocene jaguar from around 20,000 years ago. Many millennia later, Cherokee Indians, led by Chief Craighead (the cave’s namesake), used the murky depths as a council chamber. Confederate soldiers mined here for saltpeter to create gunpowder. Moonshiners used parts of the spacious cave to distill their potent product. Later, the cave system housed everything from dance floors to a mushroom farm to a cockfighting ring to a fallout shelter.

Photograph courtesy of the Lost Sea

In 1965, the Lost Sea found a new calling as a tourist attraction. Each year, thousands navigate the mile-long path through the caves with the help of a tour guide, then step aboard glass-bottomed boats that ferry them around the clear blue lake hidden inside the cavern. Peering into the water, it’s easy to spot rainbow trout, most of them blind. The first such trout were placed in the lake in the sixties to see if they could find a way out of the Lost Sea. They didn’t—but they proved to be such an intriguing attraction in their own right, they are now restocked every few years. (They can’t naturally reproduce in the lake.)

Photograph courtesy of the Lost Sea

The lake and cave system is also home to significant geological structures, including anthodites—or “cave flowers”—one of the rarest cave formations in the world. The nationally registered natural landmark holds half of all known formations of the icy-looking crystals.

But besides these ever-evolving “flowers,” you’ll find only remnants of the cave’s past lives: black carbon on the cave’s roof from the smoke of the Cherokees’ fires; a leaching vat from Confederate soldiers; a moonshine still; dilapidated boxes of rations from a 1960s bomb shelter. Forget rooms of artifacts tucked neatly behind glass enclosures: At the Lost Sea Adventure, you can get up close and personal with the cave’s wonders. Dip your hand into the lake, rub a bear claw–shaped stalagmite for good luck, or get a “cave kiss” from the overhanging stalactites.

Photograph courtesy of the Lost Sea

Choose from several tour options: an hour-and-fifteen-minute daily tour that takes you around the cavern and lake; an overnight Wild Cave Tour, where you’ll spend the night in the cave and get dirty while crawling through nooks and crannies (groups of twelve or more only); or the Super Saturday Adventure, a three-hour daytime version of the Wild Cave Tour. While you’re there, stop by the Lost Sea Village (open spring and summer), which includes a restaurant, general store, gem mine, and glass blower.

With no identified end to the lake and the water-filled rooms beneath it, there’s still much to be discovered in Craighead Caverns. Will we ever know the full scope of the Lost Sea? Perhaps not for another millennium—a mere moment in the cave system’s long and storied lifetime. —E.H.

More to Explore

Illustration by Michael Robertson

Towering Achievements

One of the South’s most beautiful towers, commonly known as Bok Tower, was built in 1929 in Lake Wales, Florida. The 205-foot neo-Gothic and art deco Singing Tower (so named for the sixty-bell carillon it houses) rises over a 250-acre woodland garden designed by Frederick Law Olmstead Jr. And while visitors may not climb to the top, the tower certainly sends spirits soaring during twice-daily live bell concerts.

Another sky-high Sunshine State structure, the Citrus Tower in Clermont, began whisking visitors 226 feet up to its observation deck in 1956. During its early days, more than half a million guests a year took in the bird’s-eye views of glittering spring-fed lakes and orange groves stretching to the horizon. Today, most of the trees have given way to strip malls and single-family homes, but the nostalgic appeal—and a small display with early renderings, archival photos, and newspaper clippings—remains intact.

Unlike the Citrus Tower, the 407-foot Space Needle in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, affords views largely unchanged since its 1970 opening. One of many towers that sprung up across the country in the sixties following the construction of Seattle’s Space Needle for the 1962 World’s Fair, the attraction continues to sell tickets to its open-air observation deck that are good for twenty-four hours after purchase, allowing guests to ride the glass elevators to the top and take in the Great Smoky Mountains by day and night.

Photograph courtesy of Marineland

Sea Change

Aquatic attractions have evolved alongside our understanding of ocean life. Case in point, Marineland Dolphin Adventure in St. Augustine, Florida. Some time after it opened in 1938, its namesake stars jumped through hoops; today, they delight visitors by showcasing their natural behaviors, such as blowing bubbles. Also in vogue? Interactive experiences. At Marineland, which is owned by the Georgia Aquarium, visitors can get in the water with dolphins—the same is true at Theater of the Sea in Islamorada, Florida. Theater of the Sea opened in 1946 and is the country’s second-oldest sea attraction, after Marineland.

Photograph courtesy of Ripley's

Believe it or Not

If it’s shocking, strange, or just plain weird, it likely has a home at one of the Ripley’s Believe It or Not! museums. The first temporary Odditorium premiered at the World’s Fair in 1933, followed by appearances at other expositions; the first permanent one opened in 1950 in St. Augustine, Florida, inside a circa-1887 Moorish-style castle that was once the home of William G. Warden, of Standard Oil Company fame. Each Odditorium (there are thirty) is housed in an unusual building (a cruise ship run aground, a toppled Empire State Building) and features between 400 and 700 exhibits showcasing everything from a six-legged cow to a shrunken human head. Ripley’s operates additional locations in Florida, as well as ones in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and Gatlinburg, Tennessee.

Nearer, My God, to Thee

Behind many a monument is man’s search for meaning. Sometimes the tribute is oversized, as it is at Fields of the Wood in Murphy, North Carolina. This biblical theme park includes a rendering of the Ten Commandments so large it can be seen from 5,000 feet in the air. Another awe-inspiring memorial, the Great Cross, can be spotted along the banks of the Matanzas River in St. Augustine, Florida. Standing 208 feet tall, it’s reportedly the country’s largest cross.

Illustration by Michael Robertson

Other times, tributes are small in scale. Take, for example, the Ave Maria Grotto in Cullman, Alabama, where visitors can see miniature replicas of the world’s great religious structures, such as St. Peter’s Basilica, made by a Benedictine monk. Using stone, concrete, and donated materials (marbles, shells, costume jewelry), Brother Joseph Zoettl created 125 tiny buildings over a nearly fifty-year period. In a similar vein, a minister in Lucedale, Mississippi, built Palestine Gardens, a scale model of the Holy Land, featuring Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and the River Jordan.

Lastly, tributes may be true to size, as is the case at Christ in the Smokies in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Visitors here can see more than 130 figures in fourteen life-size dioramas depicting scenes from the life of Jesus Christ.

Illustration by Michael Robertson

Gators Galore

Is there an animal more primal, more quintessentially Southern, than the alligator? See more than 2,000 of the snapping, prehistoric-looking reptiles, including two rare leucistic, or white, alligators (there are only twelve in the world), at Orlando’s Gatorland, which opened in 1949. Also in Florida, don’t miss the St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park, founded in 1893. It boasts a bird rookery (alligators help keep avian predators at bay) and is the only place in the world with all twenty-four recognized species of crocodilian.

Where the Lion is King

As the nation’s first drive-through safari park, Lion Country Safari in Loxahatchee, Florida, debuted the notion of a “cageless” zoo when it opened in 1967. Cruise through at eight miles an hour and spot giraffes, zebras, lions, and more. No convertibles allowed!

In Memoriam

While many of the South’s favorite attractions have stood the test of time, some live on only in snapshots, souvenirs, and memories.

Cypress Gardens: This Winter Haven attraction was once one of central Florida’s biggest tourist draws. It began life as a botanical garden in 1936, and during its heyday in the fifties and sixties, it was well-known for its water ski shows and hoop-skirted Southern belles strolling the grounds. Though it hung on for decades, adding thrill rides and a water park in the early 2000s, it was ultimately shuttered in 2009. Today, it is the site of Legoland Florida, and while the belles are gone with the wind, visitors may still stroll the historic gardens and take in a ski show performed by Lego pirates.

Illustration by Michael Robertson

Frontier Land: Opened in 1965 in Cherokee, North Carolina, this Old West–themed park entertained visitors with train rides, a gondola, several carnival-type rides, and, according to a park press release, “an Indian attack on the pioneers and soldiers every hour throughout the day.” Converted into a waterpark in 1983, it was finally razed in the mid-nineties to make way for Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort.

Magic World: Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, has seen many an attraction come and go. Among the most unusual was this mashup of dinosaurs, thrill rides, UFOs, even an Arabian village complete with a magic carpet ride. The park lasted from the mid-sixties until 1995; only the volcano, which served as the park’s centerpiece, remains. (It’s now the focal point of Professor Hacker’s Lost Treasure Golf.)

Porpoise Island: Another bygone Pigeon Forge destination, this Polynesian-themed attraction offered visitors in the seventies and eighties a taste of the South Pacific in the Smokies. Today, the dolphin lagoons and hula dancers have given way to a shopping and entertainment complex dubbed The Island. Instead of the nightly luau, visitors can book a table at Paula Deen’s Family Kitchen or Margaritaville.

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of Southbound.