Photograph by Jeff Wolk

Cryotherapy

I pull my bathrobe tighter around me as a white fog, like the smoke from a witch’s cauldron, billows from the top of the tall, cylindrical booth. I’m supposed to get inside this silvery contraption, where -270°F nitrogen-spiked air will chill me from a normal 98.6 degrees to a frosty 30 degrees? All while wearing nothing but underwear, gloves, cotton socks, and fuzzy boots? Yep, says the technician, who opens the door and coaxes me in for a session at Icebox Cryotherapy in Buckhead.

I’m paying a first-time fee of $25 to freeze my butt off in what looks like a sterile doctor’s office so, the pitch goes, I can rid myself of muscle soreness, fatigue, signs of aging—all thanks to cryotherapy, a rehabilitation and recovery technique that first emerged in Japan in the 1970s.

Cryotherapy fans say the treatment is a godsend, offering the anti-inflammatory benefits of an ice bath in a fraction of the time and with less tissue damage. If you’re a CrossFitter, say, whose lower back is sore from dead lifts, cryotherapy is said to allow for faster muscle repair and decreased recovery time. At the same time, it promises to boost circulation and even appearance, firming skin and improving hair growth.

Actual scientific evidence for these claims is limited and mixed. A 2004 study in the Journal of Athletic Training found that it may be effective in decreasing pain. But a decade later, a study in the Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine found that the therapy does little more than alleviate some muscle soreness and doesn’t aid in healing.

In fact, sports medicine experts are starting to reconsider whether cold and ice are indeed crucial components of an athlete’s recovery. Even Dr. Gabe Mirkin, who in 1978 coined the acronym RICE (for rest, ice, compression, elevation) as the go-to treatment for injuries, now believes ice could actually delay, rather than speed, healing. He says cold can shut off the blood flow to an injury, impeding the delivery of inflammatory cells and hormones that help repair damaged muscles.

On top of that, cryotherapy is not without risks. Doctors caution that extreme cold could be dangerous for those with certain preexisting conditions, like pregnancy or a history of heart disease, high blood pressure, or seizures. The industry is also largely unregulated, although that’s beginning to change after a spa worker in Nevada asphyxiated inside a cryotherapy chamber last fall.

As I warily eye one of Icebox’s frigid tubes, a frequent client turns to me and says, “You are going to love this.”

I step inside the chamber, and the technician shuts the door, so that only my head and neck are visible from the open top. Then I pass her my robe. It’s chilly, but I’ve lived in upstate New York and Chicago, and I tend to sweat in even mild weather, so I figure this shouldn’t be tough. Then she turns the temperature down—way down. I barely have time to shiver before my whole body tenses. My heartbeat speeds up, and I start to breathe in short bursts, kind of like I did when I was in labor. The technician tries to distract me with small talk. Then comes a painful pins-and-needles feeling. Just when I think I can’t stand it any longer, my three-minute session is done.

I ride home on that 70-degree day with the seat heater on, feeling a bit rested and peaceful, like you might after a massage, though I’m not quite a blissed-out puddle. Some discomfort in my shoulder from a yoga handstand gone wrong is still there. My cheeks are red, like I just went skiing. The chill hangs on for the next several hours, but the promised cryo-euphoria seems to elude me. Perhaps I need more sessions? Icebox recommends doing five to 10 treatments in close succession to maximize results. Maybe I’ll go back after I fully thaw out. —Christine Van Dusen

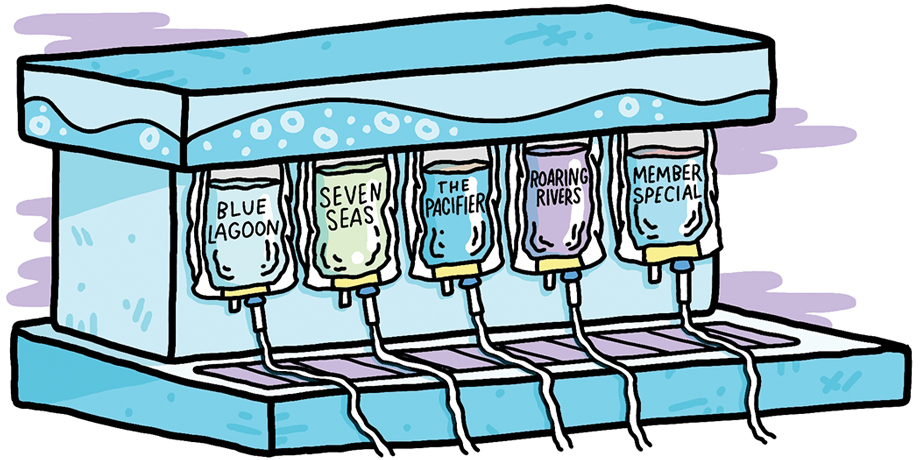

Hydration Therapy

“I have to get drunk,” I tell my wife. “For work.”

It’s been years since I swapped my post-collegiate beer-guzzling ways for those of a responsible dad, so on the rare occasion when I go overboard, it isn’t pretty. Getting inebriated typically results in a full-body flu-like malaise the next day. But it doesn’t have to be that way, according to adherents of hydration therapy, which promotes relief from hangovers (as well as overzealous workouts) by way of intravenous infusions of saline, vitamins, and medications.

So I call the Brookhaven office of Vida-Flo: The Hydration Station, founded three years ago in Buckhead by Atlantan Keith McDermott. I explain to the friendly receptionist that I expect to be wrecked on Saturday morning and agree to the “Blue Lagoon” treatment, a $49.99 first-timer’s special. Friday night I scarf a huge cheeseburger and arrange an arsenal of booze. After downing a whopping 10 drinks, I awake with a scratchy throat, nausea, a throbbing headache, and a tongue like a rock. I take a few sips of water and set out to flush the toxins.

According to McDermott, Vida-Flo was the first of its kind in the country—a “Hangover Heaven” bus in Las Vegas notwithstanding—and has since been copied from New York to Newport Beach. McDermott partnered with a board-certified physician to develop a menu of treatments, all of which provide hydrating fluids and a mix of vitamins and medications that treat heartburn, nausea, and other post-revelry ailments. Beyond the alcohol-inflicted, McDermott says treatments with names like “Seven Seas” and “Roaring Rivers” are popular with jet-lagged travelers, marathoners, and CrossFit enthusiasts. “This is not snake oil,” he says. “It’s done a thousand times a day in hospitals across the country.”

Although the science behind the treatments is solid—fluids do replenish sapped muscles, and Pepcid will settle a tumultuous tummy—some experts remain wary of the clinics themselves. Dr. Ziad Kazzi, a medical toxicologist and Emory University associate professor of emergency medicine, cautions that IV-based treatments, if haphazardly administered, can lead to infection as well as complications for customers with other health conditions, like diabetes or kidney problems. (McDermott says the clinics meet rigorous safety standards, and all treatments are performed by medical professionals.) Then there’s the question of whether you really need an IV to do a job that copious glasses of water and a few Tylenol could also accomplish (though perhaps not as quickly).

Nonetheless, Vida-Flo counts more than 1,000 “members” in Atlanta who pay a $40 to $60 monthly subscription fee, which buys one treatment. The spa-like clinic at Town Brookhaven has several private rooms and comfy leather recliners. After I enter (queasily), a receptionist leads me to a small room. I’m handed a medical questionnaire and introduced to a paramedic in blue scrubs, who checks my vitals and quizzes me about my lifestyle and “symptoms.”

Based on my replies, he whips up a one-liter rally pack full of what looks like pickle juice but is actually a mix of saline, electrolytes, vitamins, an anti-nausea drug, and an anti-inflammatory. Then he inserts a catheter into my arm, affixes a nasal cannula streaming 93 percent oxygen, and mercifully turns down the lights on his way out. Within five minutes, my nausea and headache are fading. Soon I’m no longer thirsty.

My mouth fills with what seems like the aftertaste of an energy drink. After about 30 minutes, the bag is empty.

Fifteen minutes later, driving home, my head still thumps a little, and while the hangover is no longer a hindrance, I can’t exactly imagine myself jogging into work. After a bellyful of Zaxby’s and Diet Coke, it feels like the dying stages of a regular hangover, cured finally by a nap. As a nonmember, though, the cost of my relief isn’t cheap: $64 including tip, and that’s after a first-visit discount. (A second treatment a week later set me back $140.) The cost—and the lifelong terror of needles that the treatments reawakened—will probably steer me toward an old-fashioned hangover cure next time. Like Zaxby’s. —Josh Green

Photograph by Jeff Wolk

Salt Therapy

Legend has it that, unlike coal miners with their blackened lungs, salt miners in the mid-1800s had no respiratory ailments and even emerged happy after toiling underground for days at a time. Their secret: the salt itself, which was credited with reducing inflammation in the workers’ airways and creating negative ions, invisible particles that some people say can lessen stress and contribute to a feeling of well-being. (Consider that serene feeling you get inhaling the salty ocean air at the beach.)

I may not have the stress levels of a miner, but I do have two kids and more than one job. I figure it can’t hurt for me to take a crack at a modern version of the salt miner’s experience. So I make an appointment at Salt Therapy of Georgia in Smyrna, where $30 gets you 45 minutes of halotherapy (from the Greek word for “salt”), designed to mimic the experience of hanging out in a salt cave.

Long a popular folk remedy in Eastern Europe, halotherapy eventually migrated to the U.S. Today halotherapy spas line their walls with salt blocks, and some also pump the air full of salt particles, which, according to businesses like Salt Therapy of Georgia, soothe bronchial passages, improve respiration, and clear out mucus.

There’s little research out there on halotherapy, though a few studies show there may be something behind it. For example, a 2006 study found that inhaling saline vapor improved breathing for patients with cystic fibrosis, while a second study from the same year showed that it lessened respiratory symptoms for patients with asthma. And there’s evidence that using a salt-based nasal wash (in a neti pot, for instance) can clear germs and mucus from inside the nose, helping fight congestion. But some doctors are skeptical that the lower concentration of salt inside a simulated cave would be as effective.

“I don’t know enough to say that it’s a bunch of bunk,” admits Dr. Roy Schottenfeld of North Fulton Ear, Nose & Throat Associates in Roswell. “But I wouldn’t think you’d get enough aerosolized sodium chloride to make a big impact.”

As an allergy sufferer and a singer with a frequently sore throat, I decide to give it a try anyway. After replacing my shoes with paper booties, I recline in one of the salt room’s several lawn chairs, tuck myself under a yoga blanket, and relax to the piped-in spa music. The salt lamps give off an amber glow and, supposedly, soothing negative ions. The walls are crusted with pink and white salt and the floors are covered in pebbles of salt (I know because I licked one to make sure it wasn’t just white driveway gravel). I can’t see or smell the salt dust in the air, but after about 10 minutes I can taste a hint of it on my lips.

Moments later, I’m inside a delicious nap. Was it because of the negative ions? Or was I just tired from my near-miner levels of stress and exhaustion? Days later my allergies felt about the same, as did my throat. Still, whatever the true benefits, halotherapy proved to be a lovely respite, at the very least. —Christine Van Dusen

This article originally appeared in our January 2016 issue.

Want more articles like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for our LiveFitATL emails: