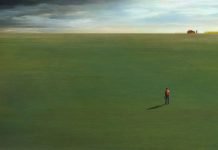

Photograph by Steven Karl Metzer

Everywhere Jason Smith turned, it seemed death surrounded him. As a medic in the smoldering battlegrounds of Iraq, he performed CPR on fatally wounded Marines. Back home he was involved in a car wreck that left him with a traumatic brain injury and killed a friend.

Before long he began hallucinating. There were daytime visions of dying men at his feet. In the grocery store, Smith saw the smiling ghosts of uniformed Marines waving. He was diagnosed in May 2005 with post-traumatic stress disorder.

The following year Smith, 33, was discharged after two tours in Iraq. Back in civilian life, he held and lost eight different jobs, largely due to symptoms relating to his PTSD. After a period of hardship and heavy drinking, Smith finally found comfort doing something he’d never done before: picking up a paintbrush.

These days the walls of the Gainesville, Georgia, home he shares with his wife, Pamela, are decorated with paintings and mixed-media artwork incorporating found items like feathers, vinyl records, and gnarly chunks of driftwood. Pop culture is a dominant theme—think ThunderCats cartoons, Iron Maiden album covers, and Duke’s Mayonnaise jars—but it’s not all lighthearted. One painting features a man dangling from a cliff; a group of soldiers grasp at him from below, trying to pull him down. “The chasm represents PTSD and memories and intrusive thoughts,” says the burley, bearded Smith, who swears by the healing power of the creative process.

He’s not alone, according to Sandy Springs native Melissa Walker, who facilitates art therapy at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence, a military treatment facility in Bethesda, Maryland, dedicated to service members suffering from traumatic brain injuries and PTSD.

“It’s difficult for them to verbalize what they’ve been through, so traditional talk therapy doesn’t always work,” Walker says. “The art-making process accesses other parts of the mind.”

Marquetta Johnson, a longtime art therapy instructor in Atlanta, says creative pursuits help veterans with PTSD become more at ease and willing to share their experiences.

Whether in a group setting or at home, troubled veterans “take these invisible wounds . . . and create a visual voice,” Walker says. “They’re making the invisible visible.”

Most of Smith’s invisible wounds stem from his time as a Navy medic serving with a Marine Corps unit in Iraq. On a mission in Haditha in 2004, a Humvee in his platoon hit a soft spot in the sand and crashed. The vehicle commander, a close friend, died in his arms as Smith attempted to revive him.

The wreck a year later left more tangible scars. A few days into a stateside military leave, Smith and a friend got into a car after they’d been drinking. His friend took the wheel.

“He lost control at around 120 miles per hour,” Smith says. “We went airborne and hit a telephone pole.”

He doesn’t remember much else because of the brain injury. The hallucinations started about three months later. At the time of his diagnosis, the Department of Veterans Affairs rated his level of disability at 80 percent, meaning he may never work again.

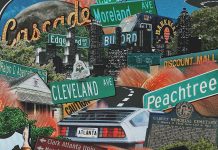

In early 2013 Smith moved from North Carolina to his wife’s hometown of Gainesville. Soon after, he began making pencil sketches, then turned to painting, sharing his work with the owner of an arts and crafts store down the road.

“She told me, ‘You ought to try making your own frames instead of buying picture frames,’ and that’s where I got the idea to use found objects,” Smith says.

Pamela sells his folk art online and has helped get his work featured in local galleries like the Quinlan Visual Arts Center. Smith says he’s come a long way since he first started painting. The best he can figure, art helps because it’s cathartic.

“[My art] gives me somewhere to put energy that I have no other way to get rid of,” he says.

Still, Smith remains on a range of medications. Walker says art is not a standalone treatment but is used alongside traditional care like drugs and counseling.

Even if Smith is never able to hold a job, he says he’s found a calling in life—one that helps him work through the invisible wounds of his past.

“Without my art, I would not be anywhere near where I am today,” he says.

This article originally appeared in our April 2016 issue under the headline “Picturing recovery.”