This article originally appeared in our August 2012 issue.

Like ghosts rising out of a Confederate cemetery, Atlanta’s past lapses in judgment haunt the region today, leaving a smoky trail of suburban decay, declining home values, clogged highways, and a vastly diminished reputation.

Like ghosts rising out of a Confederate cemetery, Atlanta’s past lapses in judgment haunt the region today, leaving a smoky trail of suburban decay, declining home values, clogged highways, and a vastly diminished reputation.

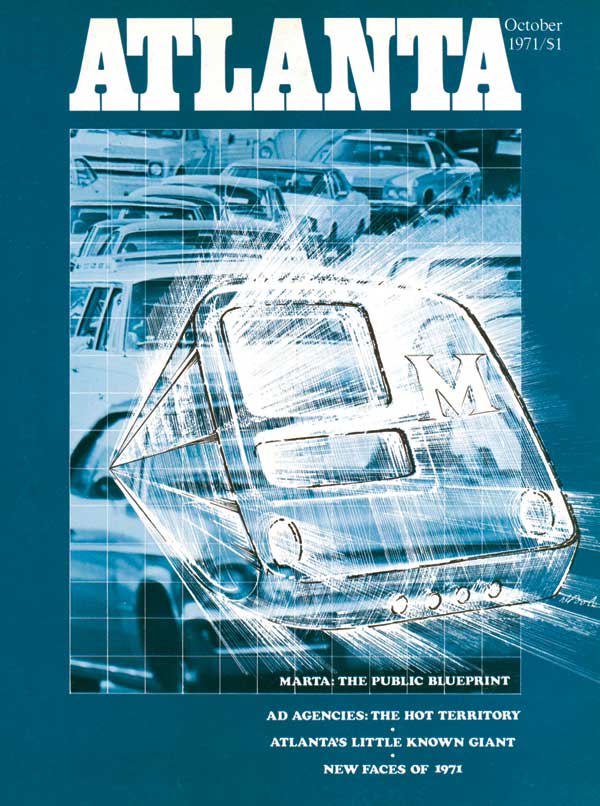

At the heart of the rot eating at metro Atlanta is the Mother of All Mistakes: the failure to extend MARTA into the suburbs. It wasn’t just a one-time blunder—it was the single worst mistake in a whole cluster bomb of missteps, errors, power plays, and just plain meanness that created the region’s transportation infrastructure.

As we look at the future of Atlanta, there’s no question that battling our notorious traffic and sprawl is key to the metro area’s potential vitality. What if there were a Back to the Future–type option, where we could take a mystical DeLorean (heck, we’d settle for a Buick), ride back in time, and fix something? What event would benefit most from the use of a hypothetical “undo” key?

The transit compromise of 1971.

Before we get into the story of what happened in 1971, we need to back up a few years. In 1965 the Georgia General Assembly voted to create MARTA, the mass transit system for the City of Atlanta and the five core metro counties: Clayton, Cobb, DeKalb, Fulton, and Gwinnett. Cobb voters rejected MARTA, while it got approval from the city and the four other counties. Although, as it turned out, the state never contributed any dedicated funds for MARTA’s operations, in 1966 Georgia voters approved a constitutional amendment to permit the state to fund 10 percent of the total cost of a rapid rail system in Atlanta. Two years later, in 1968, voters in Atlanta and MARTA’s core counties rejected a plan to finance MARTA through property taxes. In 1971—when the issue was presented to voters again—Clayton and Gwinnett voters dropped their support, and MARTA ended up being backed by only DeKalb, Fulton, and the City of Atlanta.

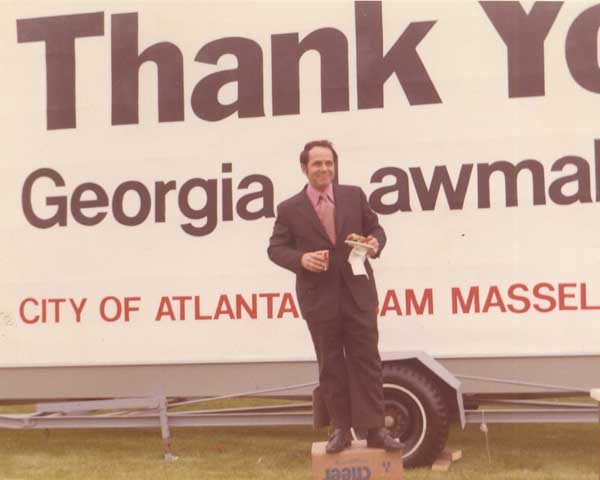

In 1971, given the lack of support for MARTA by the five core counties, then Mayor Sam Massell came back with a new plan: to provide an ongoing subsidy for MARTA through a sales tax levied in Fulton, DeKalb, and the City of Atlanta. No other jurisdiction in Georgia had a local option sales tax, so the General Assembly had to approve the idea. When the notoriously anti-Atlanta legislators gave the go-ahead, Massell called a press conference that featured a flatbed truck pulling up in front of city hall, facing the Capitol, with a large billboard that said, “Thank You, Georgia Lawmakers!” Massell then dug a hole in the city hall lawn and buried a hatchet to symbolize his appreciation for the state’s rare support of the city.

In a promotional stunt worthy of Mad Men, Massell sent a bevy of young women to the Capitol in pink hot pants with little keys to the city, a proclamation expressing the city’s gratitude, and invitations to city hall for a lunch featuring fried chicken (for Lieutenant Governor Lester Maddox), peanuts (for Governor Jimmy Carter), and, of course, Coca-Cola. “We got a four-column picture—the biggest exposure we ever got from the Atlanta newspapers,” recalls Massell, now president of the Buckhead Coalition.

After getting the legislative approval for the sales-tax option, Massell had to persuade voters to pass the sales tax. “We were going to buy the existing bus company, which was then charging sixty cents and a nickel transfer each way—$1.30 a day—and they were about to go out of business. I promised the community we would drop that fare to fifteen cents each way immediately,” Massell says. The daily fare would plunge from $1.30 to thirty cents. Not everyone believed him. City Councilman Henry Dodson cruised the city in a Volkswagen with a PA system that blared, “It’s a trick! If they can’t do it for sixty cents, how are they going to do it for fifteen?”

Massell countered the VW with higher visibility, chartering a helicopter to hover over the Downtown Connector, congested even then, while he called through a bullhorn, “If you want out of this mess, vote yes!”

“This being the Bible Belt, they thought God was telling them what to do,” Massell quips today. Still, to make sure Atlantans voted his way, he rode buses throughout the city, passing out brochures to riders, and he visited community groups with a blackboard and chalk to do the math on the sales tax. Voters approved the plan by just a few hundred votes.

Another of the blunders that crippled MARTA at the outset—and haunts it to this day—was engineered behind closed doors by the segregationist Lester Maddox, according to Massell, who believes Maddox’s intervention was even more devastating than the vote not to extend MARTA into the suburbs.

After the Georgia House of Representatives approved funding MARTA through the sales tax, Massell had to approach the Georgia State Senate, where Maddox held sway. Maddox told the mayor he would block the vote in the senate unless MARTA agreed that no more than 50 percent of the sales tax revenue would go to operating costs, Massell recalls. “He called me into his office and told me that was it. Either I swallowed that or he was going to kill it and it would not pass.”

That has meant that whenever MARTA needed more money for operating expenses, it had to cut elsewhere or raise fares. As a result, MARTA has raised the fare over the years to today’s $2.50, making it one of the priciest transit systems in the country.

Although the 50 percent limit has resulted in higher fares, few people realized the ramifications of the so-called “Maddox amendment” at the time, Massell says. In fact, it actually was viewed favorably by DeKalb legislators because they were afraid MARTA would spend all its money in Atlanta before extending rail service to DeKalb, according to a thirty-six-page history of MARTA written by former State Treasurer Thomas D. Hills.

Hills’s MARTA history also illuminates why the state never contributed funds for MARTA, despite that 1966 vote that would have allowed it to. One early plan was for the MARTA sales tax to be three-quarters of a penny, with the state chipping in up to 10 percent of the cost of the system as approved by Georgia voters. But early in his administration, according to Hills’s history, then Governor Carter called MARTA attorney Stell Huie—who was on a quail-hunting trip—and said the state couldn’t afford its $25 million share for MARTA. Carter offered to raise the sales tax to a full penny if the state didn’t have to pay, and Huie agreed. The lawyer said the 1 percent sales tax plan came out of the House Committee on Ways and Means and “there was a tag end, not even part of the act, that just said the state won’t put any money in.”

Hills wrote that the events help to “explain why some representatives of state government and others in the community understand that the state’s support in allowing the local option sales tax for MARTA was a bargain in exchange for a reprieve for the state from future funding for MARTA.”

The 1965 and 1971 votes against MARTA by residents of Cobb, Clayton, and Gwinnett weren’t votes about transportation. They were referendums on race. Specifically, they were believed to be about keeping the races apart. Consider the suburbanites voting back then. The formerly rural, outlying counties had exploded with an astonishing exodus of white people fleeing the city as the black population swelled during the civil rights era. This mass migration came at a time when Atlanta was known through its public relations bluster as “The City Too Busy to Hate.”

The 1960 census counted approximately 300,000 white residents in Atlanta. From 1960 to 1980, around 160,000 whites left the city—Atlanta’s white population was cut in half over two decades, says Kevin M. Kruse, the Princeton professor who wrote White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Kruse notes that skeptics suggested Atlanta’s slogan should have been “The City Too Busy Moving to Hate.” “Racial concerns trumped everything else,” Kruse says. “The more you think about it, Atlanta’s transportation infrastructure was designed as much to keep people apart as to bring people together.”

In the early 1970s, Morehouse College professor Abraham Davis observed, “The real problem is that whites have created a transportation problem for themselves by moving farther away from the central city rather than living in an integrated neighborhood.”

The votes against MARTA were not the only evidence of the role of race in Atlanta’s transportation plans. The interstate highways were designed to gouge their way through black neighborhoods. Georgia Tech history professor Ronald H. Bayor, author of Race and the Shaping of Twentieth-Century Atlanta, says the failure of the 1971 MARTA referendum in Gwinnett and Clayton was the beginning of the region’s transportation problems because of the lack of mass transit in the suburbs. Yet his research goes back to the racial reckoning behind the route of the interstate highway system that began construction in the 1950s.

The highway now called the Downtown Connector, the stretch where I-75 and I-85 run conjoined through the city, gutted black neighborhoods by forcing the removal of many working-class blacks from the central business district. It could have been worse. The highway was first designed to run smack through the headquarters of the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, the city’s major black-owned business. “The original intention was to destroy that black business,” Bayor says. A protest by the black community saved the structure and moved the highway route a few blocks east, where it still managed to cut through the black community’s main street, Auburn Avenue.

Interstate 20 on the west side of town is a particularly egregious example of race-based road-building. Bayor wrote: “In a 1960 report on the transitional westside neighborhood of Adamsville . . . the Atlanta Bureau of Planning noted that ‘approximately two to three years ago, there was an “understanding” that the proposed route of the West Expressway [I-20 West] would be the boundary between the white and Negro communities.’”

The strategy didn’t work, of course, as whites fled by the tens of thousands. One of the unintended consequences of the race-based road-building is today’s traffic jams. “What happened didn’t change the racial makeup of the metro area but led to congestion within the metro area,” Bayor says.

Aside from political vengeance and racial politics, another enormous factor was at play in transportation policies of the 1960s and 1970s: Atlanta’s love affair with the automobile. The great migration out of the city started in the late 1950s—just as workers at General Motors’ vast Lakewood assembly plant in southeast Atlanta put the finishing touches on one of the most iconic cars in history: the 1957 Chevy.

The allure of roaring around Atlanta in cool cars took over and never let go. Once MARTA started running, who would ride a bus or subway when they could drive a sleek, powerful car and fill it with cheap gas? Only the people who couldn’t afford the car. MARTA became an isolated castaway, used primarily by poor and working-class blacks. Racist suburbanites brayed that the system’s acronym stood for “Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta.”

While MARTA was struggling to crank up the bus and rail system, the State of Georgia and its powerful highway department had other, bigger ideas.

David Goldberg, a former transportation reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, says the road-building binge that led to the gigantic highways that course through metro Atlanta—some of the widest in the world—diminished MARTA’s potential. “It’s not a single mistake but a bunch of decisions that add up to one big mistake—the failure to capitalize on the incredible success we had in winning funding for MARTA by undermining it with the incredible success we had in getting funding for the interstate highways,” says Goldberg, now communications director for Washington-based Transportation for America. “We were too damn successful—it was an embarrassment of success. Like a lot of nouveau riche, we blew it before we knew what to do with it.”

As metro Atlanta’s geographic expansion grew white-hot, developers had to move homebuyers—those fleeing the city and others moving South from the Rust Belt—in and out of the new subdivisions they were carving from the pine forests and red clay. Georgia started “building highways expressly to enrich developers,” Goldberg says. “A whole lot of land owners and developers who knew how to do suburban development had the ear of state government and the money to buy influence. They took all that money we had and put it into developing interchanges way out from town. A lot of what was new suburban development back then is now underused, decaying, and part of an eroding tax base in the older suburban areas.”

The vast highway system sucked up billions of federal dollars while the state refused to put a penny into MARTA—until the past fifteen years, during which it helped buy some buses. “The sick joke of it all is that we built the place to be auto-oriented and designed it about as bad as we could to function for auto use,” Goldberg says. “The highway network we did build was designed in a way almost guaranteed to produce congestion—the land use around all that development put the nail in the coffin.” He refers to the neighborhoods full of cul-de-sacs that force cars onto crowded arterial roads lined with commercial activity, then force them to merge onto the freeways, which eventually funnel down to one highway through the heart of Atlanta.

Photograph courtesy of Sam Massell

More than forty years later, what does the failure to create MARTA as a regional system mean for Atlanta? Christopher B. Leinberger, a senior fellow of the Brookings Institution and professor at George Washington University, has been watching Atlanta’s growth—and decline—for decades. In January he declared, “Atlanta is no longer Hotlanta.” He cited the free fall from the number eighty-ninespot on the list of the world’s 200 fastest-growing metro areas to ranking at 189 in just five years. Not to mention the plunge of 29 percent in average housing price per square foot between 2000 and 2010. Not to mention that Atlanta has the eleventh-most-congested traffic of 101 metro areas in the country.

“The big mistake was not taking advantage of MARTA,” Leinberger says. “Atlanta was given by the federal taxpayers a tremendous gift that they squandered as far as MARTA. It’s not just that Atlanta did not take advantage of it. They didn’t expand it and they didn’t recognize that it could allow them to build a balanced way of developing.”

Leinberger agrees that part of the region’s blindness toward MARTA’s potential was the belief “that the car was the be-all and end-all forever. The other part was the basic racism that still molds how Atlanta is built.”

The most maddening realization is that the once virtually all-white suburbs that voted against MARTA years ago are today quite diverse and reflect Atlanta’s evolution from a biracial city to a multiracial, multiethnic one. Today’s suburbs are not only home to African Americans, but also Latino, Asian, and Eastern European immigrants. The city’s diversity is projected to increase over the coming decades (see page 68). Many of the people who voted against MARTA decades ago are dead or retired. The suburban lifestyle they were so eager to defend has lost much of its cachet as gas prices soar and houses don’t sell. Smart young people up to their necks in college debt don’t want to spend their money and time driving cars back and forth; they want to live in town. Atlanta’s only neighborhoods to gain inflation-adjusted housing value in the past decade, Leinberger notes, were Virginia-Highland, Grant Park, and East Lake.

The Georgia Sierra Club’s opposition to the July 31 referendum on a regional transportation sales tax—on the grounds that the plan, despite including a majority for transit, was a sprawl-inducing road expansion—troubled Leinberger. “That’s a dangerous strategy. From what everybody tells me, this is a one-off.” He says the state legislature has traditionally treated Atlanta like a child, and is saying, “Finally, one time only, children, are we going to let you decide for yourself. This is it.”

The July 31 vote is “an Olympic moment,” he says. “If the vote fails, you have to accept the fact that Atlanta will continue to decline as a metro area.” Forty years from now, will we look back at failure to pass the referendum as a mistake as devastating as the 1971 MARTA compromise?

Atlanta faces a classic problem. It boomed in the go-go decades at the end of the twentieth century when everyone zoomed alone in their cars from home to office to store. Now it must move beyond what worked in the past to a new era that demands a new way of building, with up to 70 percent of new development oriented around transit, Leinberger says. “Atlanta has a lot of catching up to do, but it’s hard for old dogs to learn new tricks.”

The never-ending ramifications of a race-based transportation infrastructure, built to accommodate a suburban driving lifestyle that has started to die off in a state that has traditionally refused to embrace mass transit, could doom Atlanta to a future as a newer, sunnier Detroit.

“It only takes a generation-plus of yinning when you should have yanged to wake up and say, ‘Oh my God! How did it happen?’” says outgoing MARTA General Manager Beverly A. Scott, who watched from afar the decline of her hometown, Cleveland.

Atlanta’s failure to build out MARTA looks even more shameful when compared with what happened with similar transit systems in San Francisco and Washington, D.C., which started at the same time as MARTA, she says. “The reality is, this region got stuck. We have about half the build-out of what it was planned to be.” But San Francisco and Washington “kept building and moving . . . they had plans regardless of whether folks were red or blue. They had a vision and the fortitude to make purple and keep moving. We just got stuck.”

MARTA was born out of Atlanta’s giant ego in the days when the city was entering the major leagues across the board—baseball, football, international airport—bolstered by a racially harmonious reputation unmatched in the South, deserved or not. “You said to yourself, ‘We’re top-notch. Everybody’s got to have a rail system,’” Scott says. “But it was built as a manifestation of ‘we have arrived’ without a bigger vision of ‘what do we want to do for our region?’ You built it like a trophy.” Indeed, some of the Downtown MARTA stations were built on a scale that would please a pharaoh.

Yet Scott says she is no doomsayer. During her tenure at MARTA, she has seen marked progress in forging the civic-political infrastructure necessary to build an integrated transportation network. Her concern is that the region is at a critically urgent juncture in the process and can’t afford to lose focus or momentum.“There’s still much work to be done,” she says.

Word about Atlanta’s transportation muddle has gotten around. Scott says she’s been privy to meetings during which corporate relocation experts tell Chamber of Commerce members: “Hey, Atlanta is not only not at the top tier anymore, we’ve got companies saying, ‘Don’t put the Atlanta region on the list.’” It’s not just the congestion and pollution—“they’re not seeing leadership or plans to get yourself out of the fix.”

Atlanta’s leaderless transportation fix is the ultimate example of the admonition, “Be careful what you pray for.”

“This is the irony: The majority of whites in Atlanta wanted to be isolated when they thought about public transportation,” says historian Kevin Kruse. “As a result, they have been in their cars on 75 and 85. They got what they wanted. They are safe in their own space. They’re just not moving anywhere.”

Hindsight: Other lapses in civic judgment

The 1818 Survey Snafu That Keeps Atlanta Thirsty

Surveyors in 1818 goofed when marking the border between Georgia and Tennessee. At least that’s Georgia’s story, and we’re sticking with it. Legislators still quarrel over the alleged historical cartography blooper that left all of the Tennessee River within Tennessee. Georgia claims surveyors set the boundary line too far south by more than a mile and should have included a sliver of the mighty river within our borders. During recent severe droughts, Georgia thirsted to stick a pipe into the Tennessee and route water to Atlanta, which now draws all its H2O from Lake Lanier and the Chattahoochee River, whose water is also lusted after by Alabama and Florida. Another mistake is our failure to build additional reservoirs —just being addressed now.

The “Grow No More” Edict of 1953

The city of Atlanta hasn’t extended its boundaries in the last sixty years, while the population and landmass of the surrounding counties has exploded. The last time Atlanta expanded its limits was 1952, when it took in Buckhead and went north—almost to Sandy Springs. Timothy Crimmins, who directs the Center for Neighborhood and Metropolitan Studies at Georgia State University, thinks Atlanta’s biggest mistake—bigger than the MARTA compromises—was a 1953 decision by the state supreme court that declared unconstitutional an effort by the local legislative delegation to annex additional parts of Fulton County. The court said only the General Assembly could expand city limits—and the referendum sought to preempt that power. It was a critical opportunity that would have set up a central government that could grow with our expanding population instead of the proliferation of regional governments.

The last major effort at annexation was Sam Massell’s “Two Cities” plan of the early 1970s, which called for Atlanta to annex unincorporated Fulton County north of the city, and College Park to annex unincorporated Fulton to the south. The plan passed in the House of Representatives and was set to pass in the Senate, but it was killed by Lester Maddox. Ironically, segregationist Maddox stopped annexation that would have returned Atlanta to a majority-white city. Adjusting racial allotments “was not the motivation” for the plan, Massell says. What he was after was a city with a greater population, and thus greater power. Crimmins says Maddox killed the bill at the request of black leaders and the City of East Point.

Our Sewer Woes—Dating Back to Reconstruction

In the years after the Civil War, Atlanta built a two-pipe sewer system: a separate but integrated network of pipes that collects sewage and storm water. During downpours, rainwater forced raw sewage into the Chattahoochee. As the population grew, the pollution became grotesque. In 2001 the city agreed to federal and state demands to fix the problem with giant underground tunnels to store the overflow and then send it for treatment. The Clean Water Atlanta program has cost $1.6 billion so far and will cost another $450 million over the next thirteen years. This is why Atlantans have among the nation’s highest water-sewer bills. The situation in the suburbs may be worse because so much wastewater treatment is the responsibility of private homeowners with septic tanks. “The pollution potential for that is gargantuan,” Crimmins says.

This article originally appeared in our August 2012 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)