Photograph by Johnathon Kelso

It’s a fall afternoon, and Jessica Phillips is sitting in a log cabin and discussing Foxfire, the cultural appreciation nonprofit that for 50 years has transcribed and recorded the oral histories of vanishing Southern Appalachian folkways. Phillips, 18, is completing her fourth year of Foxfire journalism classes at Rabun County High School in northeast Georgia—like her mother, father, brother, and two aunts, who are all alums of the program.

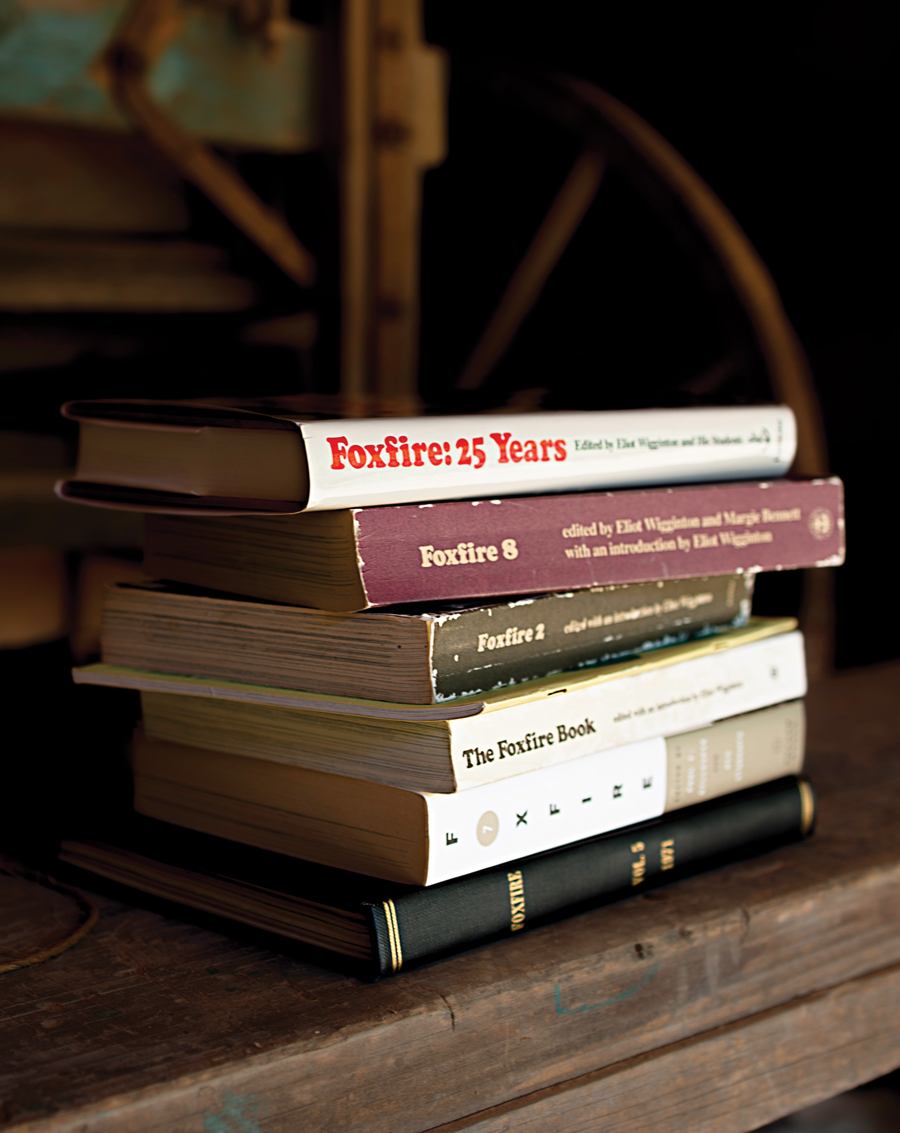

When Foxfire published its first book in 1972, the volume went through three printings and became a New York Times bestseller in just one month. Embraced by the era’s back-to-the-land enthusiasts (not unlike today’s maker movement), Foxfire became a phenomenon, inspiring bestselling books and a Tony-winning play starring Jessica Tandy.

Photograph by Johnathon Kelso

Phillips contributed to this year’s commemorative book, The Foxfire Book of Simple Living: Celebrating Fifty Years of Listenin’, Laughin’, and Learnin’. She also has coauthored, with journalist Phil Hudgins, a manuscript that will hopefully become the 22nd Foxfire book. Foxfire, she explains, has “allowed me to slow down and sit on the porch with someone and have a conversation that I couldn’t have before. It has let me make those close-knit connections.” During her research, Phillips has gathered tales of men hunting bears and women making fluffy biscuits with the rendered fat. She’s learned to savor the layers of language and tradition that make up the rich terroir of her regional heritage. “Foxfire showed me always to take pride in the Southern Appalachian community and to never want to change who you are,” she says.

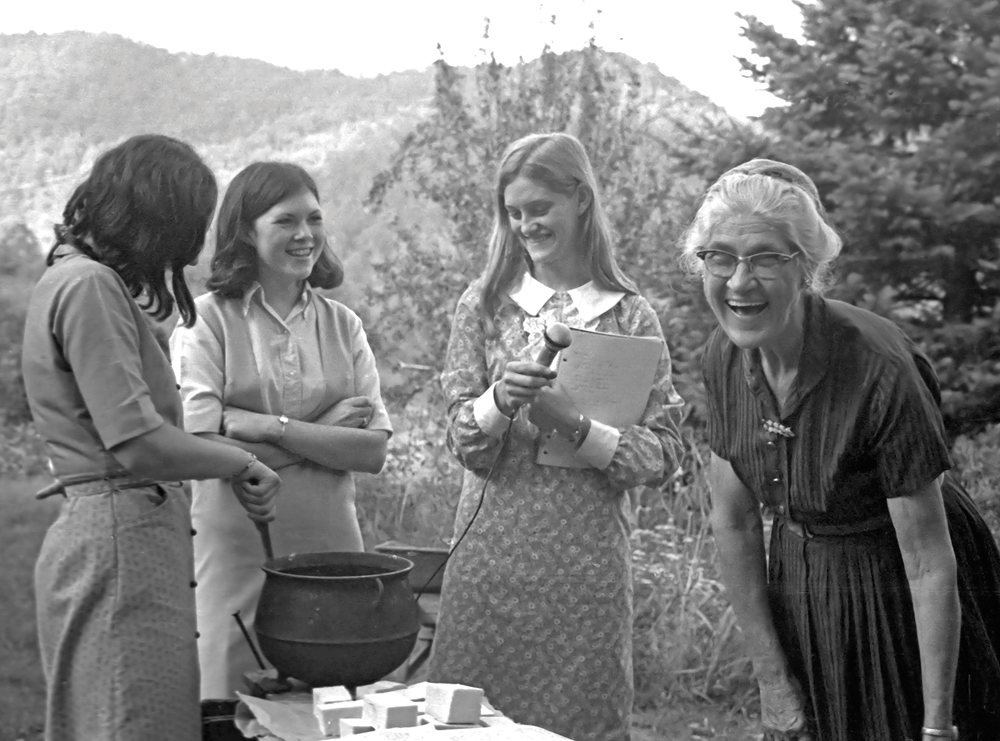

Photograph courtesy of The Foxfire Museum

Anyone who remembers Foxfire will likely recall the rise and fall of Eliot Wigginton, the gifted educator and MacArthur fellow who inspired countless students before pleading guilty to child molestation in 1992 (he was barred from Foxfire and served a year in jail, later moving to Florida). When he came to Rabun Gap–Nacoochee School in 1966, as a lanky, bespectacled first-year teacher, Wigginton failed miserably at teaching English using traditional pedagogy. He tossed the textbook and invited his ninth and 10th graders to start a magazine. Students interviewed family, friends, and elderly community members, gathering oral histories on topics such as home remedies, hog dressing, snake lore, faith healing, and moonshine. They named the magazine after an indigenous glowing fungus.

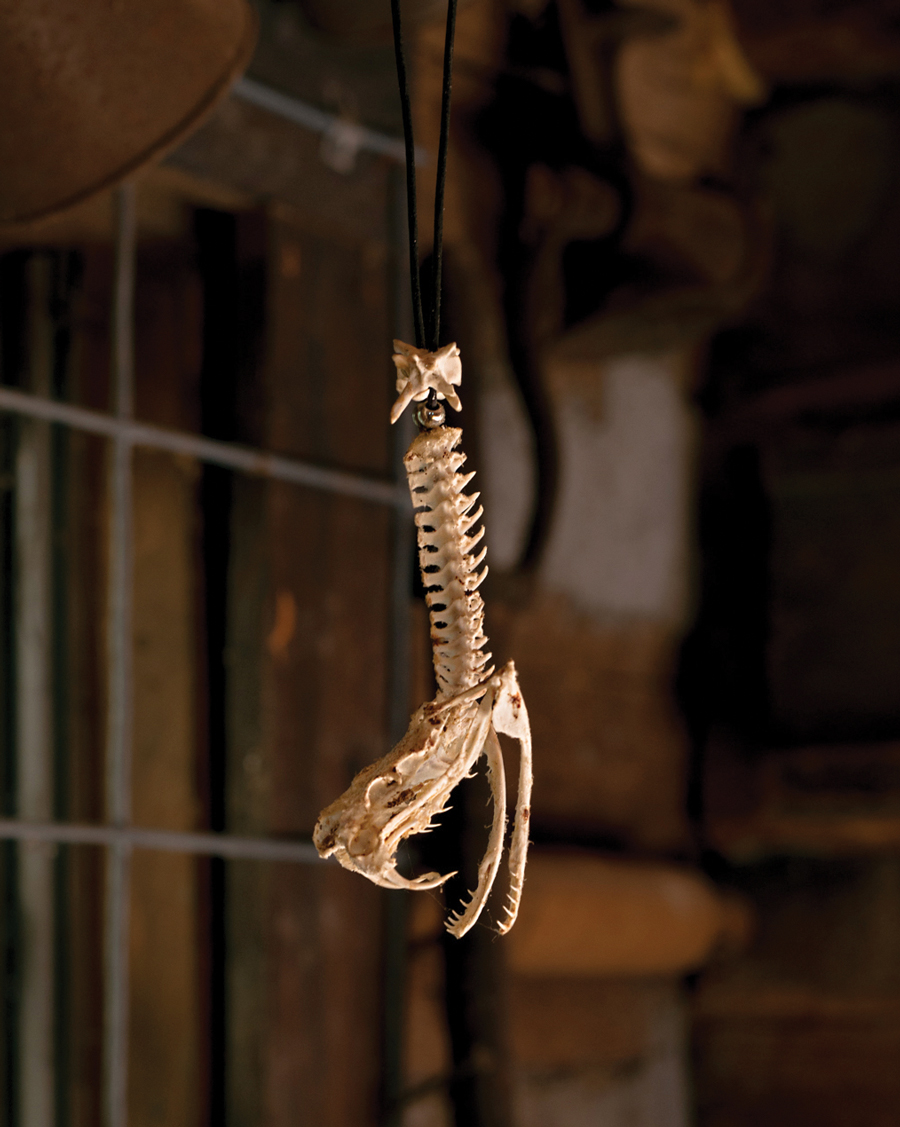

Magazine entries were compiled into that first blockbuster anthology, and two years later students used the book’s royalties to buy property on Black Rock Mountain to house artifacts donated by interview subjects. The expansive collection now includes a Lanier Meaders face jug, rattlesnake fangs, a rope bed, corn-shuck dolls, and the only known surviving wagon used to remove Cherokees on the Trail of Tears.

Photograph by Johnathon Kelso

Photograph by Johnathon Kelso

Foxfire continues to flourish as a literary and educational organization. Located on 106 acres in Mountain City, a little more than 100 miles north of Atlanta, the nonprofit is enjoying renewed popularity. Today about 20 buildings, collectively called the Foxfire Museum, nestle into a wooded slope along the Eastern Continental Divide. Authentic log cabins, relocated to the site and reassembled by students, provide a glimpse into pioneer living, a time when “you were just taking care of your family and scraping by, with no luxuries,” says Foxfire interim executive director Barry Stiles. He pauses in the dusty yard of a one-room cabin, gesturing at a wash pot where clothes were boiled. “You had to get firewood. There was no running water.”

Photograph by Johnathon Kelso

Among the museum’s 13,000 annual visitors, there are usually a few hundred doomsday “preppers,” who want to protect themselves in case of mass disaster. “Preppers have really grabbed onto Foxfire as a survival guide,” Stiles says. They see the books, which contain detailed instructions on skills such as curing meat and making soap, as essential how-to manuals for living off the grid.

In a more mainstream realm, educators are studying Foxfire’s experiential approach to learning, which stresses student choice and accountability, with teachers serving mostly as facilitators. Piedmont College offers Foxfire courses for K-12 teachers and a similar class for college instructors. This fall, nine University of Georgia professors, from the business school to the college of engineering, are studying Foxfire’s core teaching methods.

Photograph courtesy of The Foxfire Museum

One of the first fruits of UGA’s initiative is an exhibition organized by Dixie Gallups and Kimberly Ellis, two graduate students in historic preservation. On view through December 16 at the Richard B. Russell Building Special Collections Library, Foxfire: 50 Years of Cultural Journalism Documenting Folk Life in the North Georgia Mountains includes artifacts such as a copper moonshine still, an ox yoke, a bulky cassette recorder used by students, an intricate filet lace coverlet, and—of course—early magazines. The exhibition wraps up Foxfire’s year of anniversary celebrations, which have included Foxglove, an original play by Phillip DePoy at the Alliance Theatre, and a Foxfire Mountaineer Festival for alumni. UGA houses most of Foxfire’s archival material and is digitizing some of the oral histories. Library holdings include audiotapes and some 1,300 videotaped interviews.

For Jessica Phillips, Foxfire has inspired her to think big. The high school senior is taking classes at Piedmont College and wants to become a dermatologist. “I’ve realized I could do a lot.”

This article originally appeared in our December 2016 issue.