Photograph by Kaylinn Gilstrap

On a warm spring day just over three years ago, Olaf Kunkat stood at the corner of Mitchell and Forsyth streets in South Downtown. In all directions, he saw barren streets, vacant storefronts, and half-empty parking lots where buildings once stood. “It was all beauty,” he says.

Kunkat is a developer and so is occupationally obligated to see not what is but what could be. Still, South Downtown would challenge the imagination of even the most cockeyed of optimists. Bordered by Marietta Street to the north and I-20 to the south, and sandwiched between Mercedes-Benz Stadium and the Georgia Capitol, the 20-block area covering roughly 90 acres was, until the mid-20th century, arguably the heart of Atlanta. Not far from where railroad surveyors planted the Zero Mile Post, around which the city grew in 1850, railway workers and traveling businessmen fresh off trains at Terminal Station filled rooms along Hotel Row. Families bought Chattahoochee catfish on South Broad Street, and workers filled factories and offices, including the Atlanta Constitution’s newsroom. Streets were lined with brick-and-stone buildings, street-level storefronts topped by three or four floors of apartments or hotel rooms.

But in the 1960s and ’70s, white flight and the construction of the Five Points MARTA Station hollowed out the area. Buildings were demolished for parking lots to serve the growing number of government workers, sapping the area of a thriving nighttime population, save for patrons of Magic City or passengers at the Greyhound bus station.

Like other neglected areas close to the city’s core, South Downtown was an intermittent focus of attention for city planners. In 1984, with the enthusiastic backing of then Mayor Andrew Young, an investor from Singapore proposed razing much of the area to build a $1-billion, 90-acre “international town,” populated by 300 families he’d move here from Hong Kong. The plan collapsed. In the 1990s, the Sam Nunn Federal Center brought in 8,000 workers but very little lasting investment outside its walls.

Large-scale development has taken several forms in Atlanta in recent years. There’s Ponce City Market (repurpose one massive building); Atlantic Station (reclaim an industrial site by building from the ground up); the BeltLine (build luxury housing around a concrete path). Kunkat, through his Hamburg-based firm Newport Holdings, is attempting a different kind of approach, one more akin to how Candler Park and Inman Park residents revived Little Five Points—if the indie-spirited commercial district had seven-story office buildings: Instead of leveling what’s there to build something new, Kunkat wants to retrofit what’s already there, building by building.

Kunkat chose Atlanta because of its affordability, concentration of Fortune 500 companies, and growing young population. Three years since its first purchase, Newport now owns more than 48 parcels over eight blocks. For $12 million, it bought the 71-year-old C&S Bank Building at 222 Mitchell Street, where cash once traveled through pneumatic tubes. For $3.5 million, it bought the former H.L. Green Department Store building, once the site of a historic five-and-dime store, on Peachtree. On South Broad, Newport bought a cluster of buildings, including a longtime pharmacy with a basement that, prior to the construction of viaducts to span the railroad tracks, opened onto streets that are now part of Underground Atlanta. In a city more inclined to raze buildings than preserve them, South Downtown is an irreplicable snapshot of what Atlanta once was. “You can read part of Atlanta’s history there that you can’t anywhere else,” says Boyd Coons of the Atlanta Preservation Center.

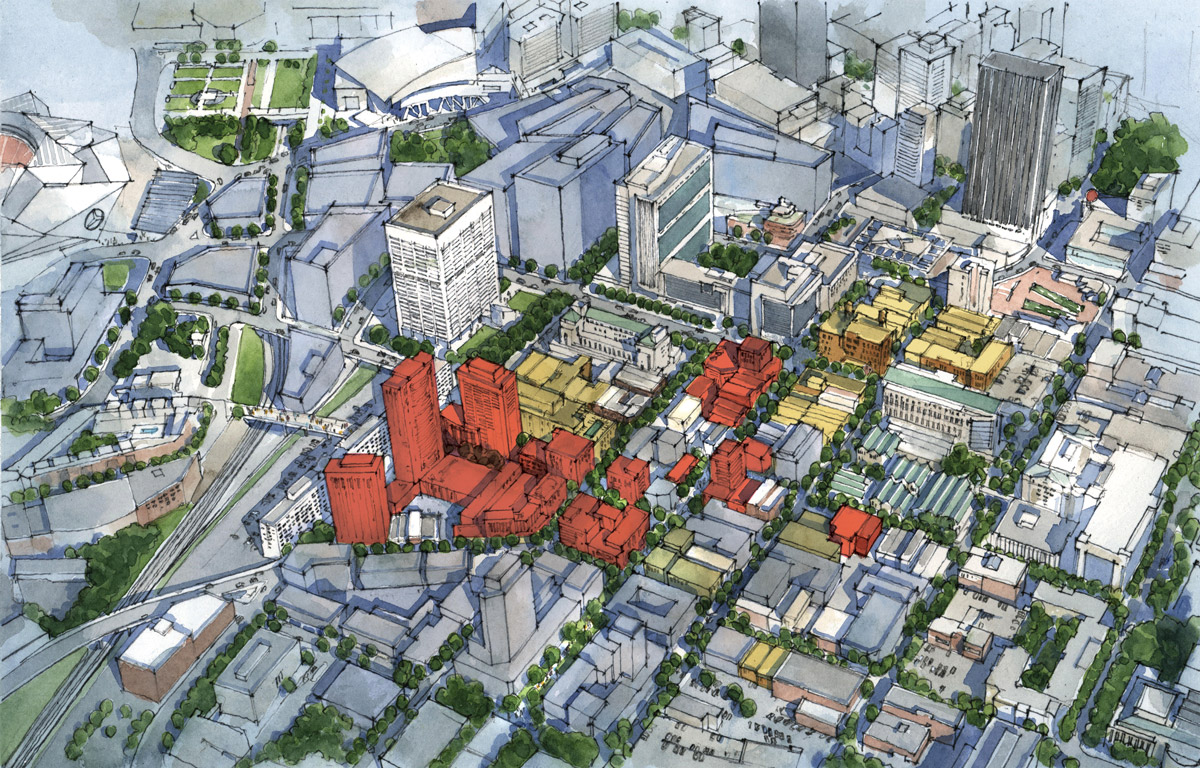

So far, Newport has spent $88 million acquiring property and has started gutting and prepping spaces. With the help of city incentives and historic-building tax credits, Kunkat wants to strip the wood and aluminum facade on a Peachtree nail salon to expose the original brick and stone and has torn out old carpet and drywall in the old Sylvan Hotel to reveal the historic brick walls beneath. Once that’s complete, Kunkat says, Newport will lease “affordable” space to a mix of restaurants, shops, and offices, build housing catering to a mix of incomes, and kick off an experiment to see whether the diverse community that once thrived in South Downtown can do so again. Kunkat believes the demand is there—from Georgia State University students, government workers, and Atlanta United fans, for starters—and will later construct new buildings on barren parking lots for apartments and offices. Throughout the process, the company plans to use different architects to ensure a mix of styles and feels.

Plan courtesy of Newport

Kunkat’s done this before, though never on such a scale. In 1993, four years after the Berlin Wall fell, he made his first investment in East Berlin’s Mitte neighborhood: a rundown former factory. “I bought the neighboring building, then the next building,” he says. But today, Kunkat says, Mitte has suffered the same double-edged sword of urban revitalization that has affected major cities around the world: Chain stores are ubiquitous, and rents are unaffordable for most people.

Kunkat hopes to avoid making the same mistake in South Downtown by seeding the community with mixed-income housing and local, creative companies at affordable rents. From there, Kunkat says, the development will unfold organically.

Rebuilding a neighborhood can be a slog, however. Building safety concerns forced the closure of Mammal Gallery, a popular DIY space on South Broad, and Eyedrum, a longtime Atlanta arts collective on Forsyth Street. (Murmur and the Broad Street Visitors Center remain.) Save for leasing space to film productions and pop-up galleries, makers markets, and indie boutiques this past April, the space feels as dead as ever. But Kevin Murphy, a Georgia Tech graduate with 10 years of experience working with historic buildings in New York, recently joined the team, and the group has signed letters of intent with two local food and beverage businesses, says Kunkat, who visits once a month to oversee the project.

Initially, Newport planned to focus on its Peachtree Street storefronts near Underground Atlanta, which has languished since WRS Real Estate bought the subterranean shopping mall from the city in May 2017. But when Newport saw the momentum behind the redevelopment of the historic Norfolk Southern Building, and CIM Group’s plan to build a mini-city in the Gulch, the company shifted its focus to 222 Mitchell, which will once again become offices, and Hotel Row across the street, where restaurants, creative offices, and shops will fill 10 empty spaces. This spring, Darren Carr—the co-owner of Big Citizen, the group that owns Midtown restaurants Bon Ton and the Lawrence—will launch a flea market along South Broad and plans a hybrid bar and art space.

Newport is backed by six German families who, Kunkat says, are patient. “We have no exit strategy,” he says. Typically, investors want a return on investment in five years, and principals sell, leaving maintenance costs to someone else. Kunkat says Newport won’t think about selling a single building for 10 to 15 years—and because the company is building a mix of uses and controls so much of its neighborhood, he argues, it can more easily withstand recessions. “If we do good here, it will change,” he says.

This article appears in our February 2020 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)