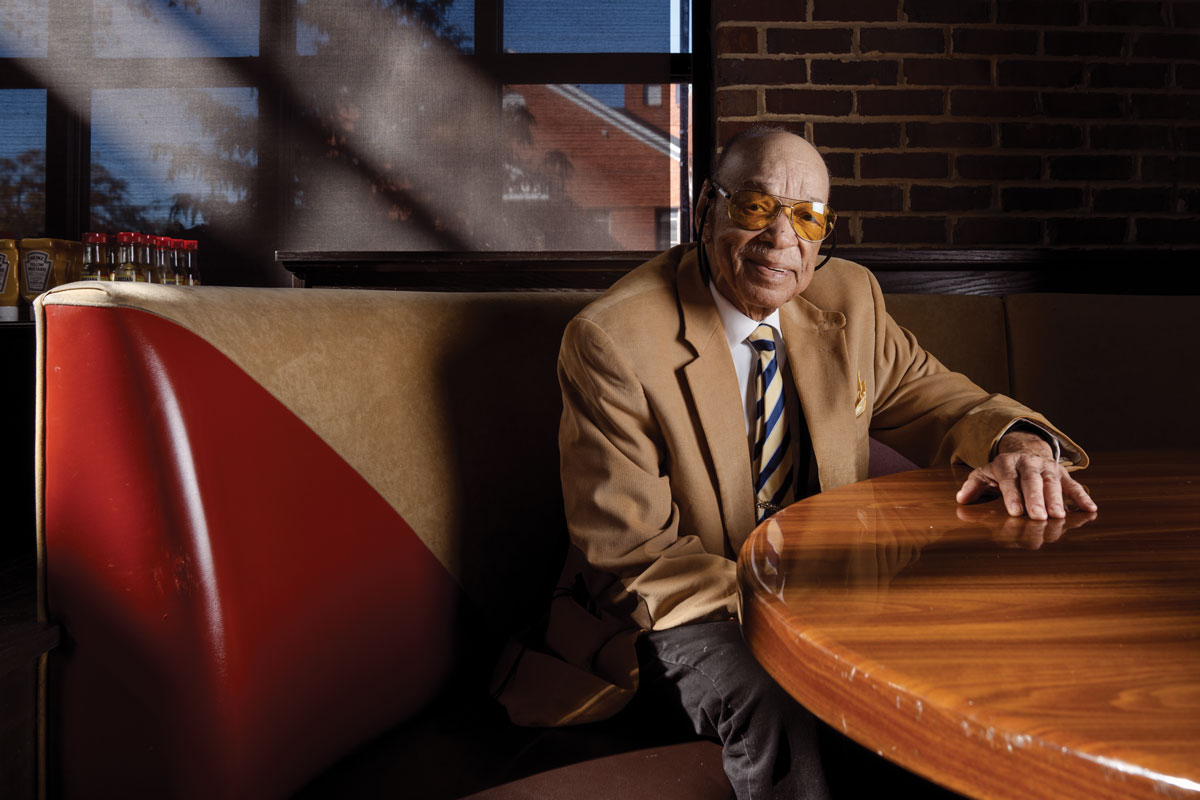

Photograph by Kevin Liles

Atlantans is a first-person account of the familiar strangers who make the city tick. This month’s is Eby Marshall Slack, an original staffer at Atlanta’s iconic civil rights-era restaurant Paschal’s, as told to Mike Jordan.

I’ve been affiliated with the Paschal brothers since way back in 1947, as a little boy. Off and on, I would do a little work around the place after school, just chores for spending change. I started working full-time in the ’60s. I was running their nightclub, La Carrousel. I was the manager for a number of years. Then, they put me over in the restaurant. I was also in charge of the banquets and affairs we had for dignitaries, fraternities, and the politically involved.

During that time, we had a lot of entertainers, such stars as Nancy Wilson, Ramsey Lewis, Lena Horne, Dizzy Gillespie, Cannonball Adderley, Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions, and on and on.

James Paschal, the youngest brother, was in the armed services and went overseas. He visited some beautiful clubs in Europe. James wanted good, consistent entertainment for people in Atlanta who didn’t have a chance to see it. A lot of people could only buy the records and see them on television or something. And it was segregated at that time. Blacks and whites could not mix.

We opened our new restaurant in 1959 [moving from the original luncheonette into a larger facility], and [James] wanted a first-class type of club; so, he decided to [add La Carrousel Lounge] in 1960.

Paschal’s was on Hunter Street, which they renamed to Martin Luther King. It was one of the main streets, besides Auburn Avenue. This is where a lot of Black businessmen started their careers and went into business for themselves. There was very little opportunity to go downtown and open up this kind of place during segregation. But they opened up on Hunter Street, which was in a predominantly Black community, with doctors’ offices, a dentist’s office, attorneys, drugstores, Black-owned barbershops and shoe shops, and restaurants, not just Paschal’s.

On the first night, it was so busy and crowded. It had a line around the corner, and you had just as many white people coming in as Black people. It was unique to see this happen in a time of segregation. Blacks and whites weren’t supposed to mix—and the most important thing: mixing and sitting down next to each other drinking alcoholic beverages. And we didn’t have any incidents whatsoever. There was no fighting, no cursing. We didn’t have it.

Mr. Paschal and his brother, Robert, would make sure the gentlemen would act right. They required you, after five o’clock, to wear a coat and tie. I asked, “Why? What’s the point?” Their belief was, when a young man is dressed, his behavior changes. He feels important. He feels like he’s king of the world, and it slows down a lot of bad activities.

We don’t have enough Black-owned businesses [today]. You had an atmosphere where we were just proud of the Black race. This is what helped Atlanta become a city that was a little bit too busy to hate.

During that time, things were not expensive. You could come to Paschal’s and get a chicken sandwich for 52 cents. Anybody could afford a good dinner. Coca-Cola was a nickel; a grilled cheese sandwich was around 65 cents. It was a different time.

The most enjoyable thing was working with a family who, in their hearts, wanted to give back to the community. They would sit down with preachers and politicians in a booth and wouldn’t let them leave unless they ordered food. And they’d discuss what was going on in the city, in the civil rights movement. How are we approaching trying to integrate downtown? And they would sit there, drink coffee, smoke cigarettes, and discuss these things.

Two brothers brought the community closer. They taught me as a young man to respect other people. They told me to get all of the education you can, and don’t ever look back. Keep going forward, work, and be dedicated to something in life. And one of the main things was, Try to love people.

Dr. King made Paschal’s his home. He loved the food. And it’s still home for his family, and Ambassador Andrew Young, who is at Paschal’s all the time now. I’m there every weekend. I answer people’s questions when they look at all the beautiful pictures of Martin Luther King, Mr. Herman Russell, and Maynard Jackson. I do anything to keep the dream of the Paschal brothers alive. And until the day I die, I’m going to finish the job.

This article appears in our January 2022 issue.