Photograph by Simon P. Barnett/Allsport/Getty Images

Seen in the context of the digital age, the events in the wake of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Park bombing feel almost prehistoric. There was no Twitter. No Facebook. Fox News didn’t even exist. Just 12 percent of Americans went online for news. And three out of four still read a newspaper—an actual printed newspaper—every day.

Today, the for-profit news model is in a steady and unmitigated freefall. More Americans get their news from their Facebook feed than from newspapers, and—go figure—the trust in our news sources is at an all-time low.

Now, in the baleful winter of our journalistic discontent, comes Richard Jewell, a feature film directed by Clint Eastwood and shot in Atlanta that recounts the Olympic park bombing, the FBI’s misguided focus on Jewell as a suspect, the leaking of his name to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and the wreckage, legal and otherwise, left in the wake of it all.

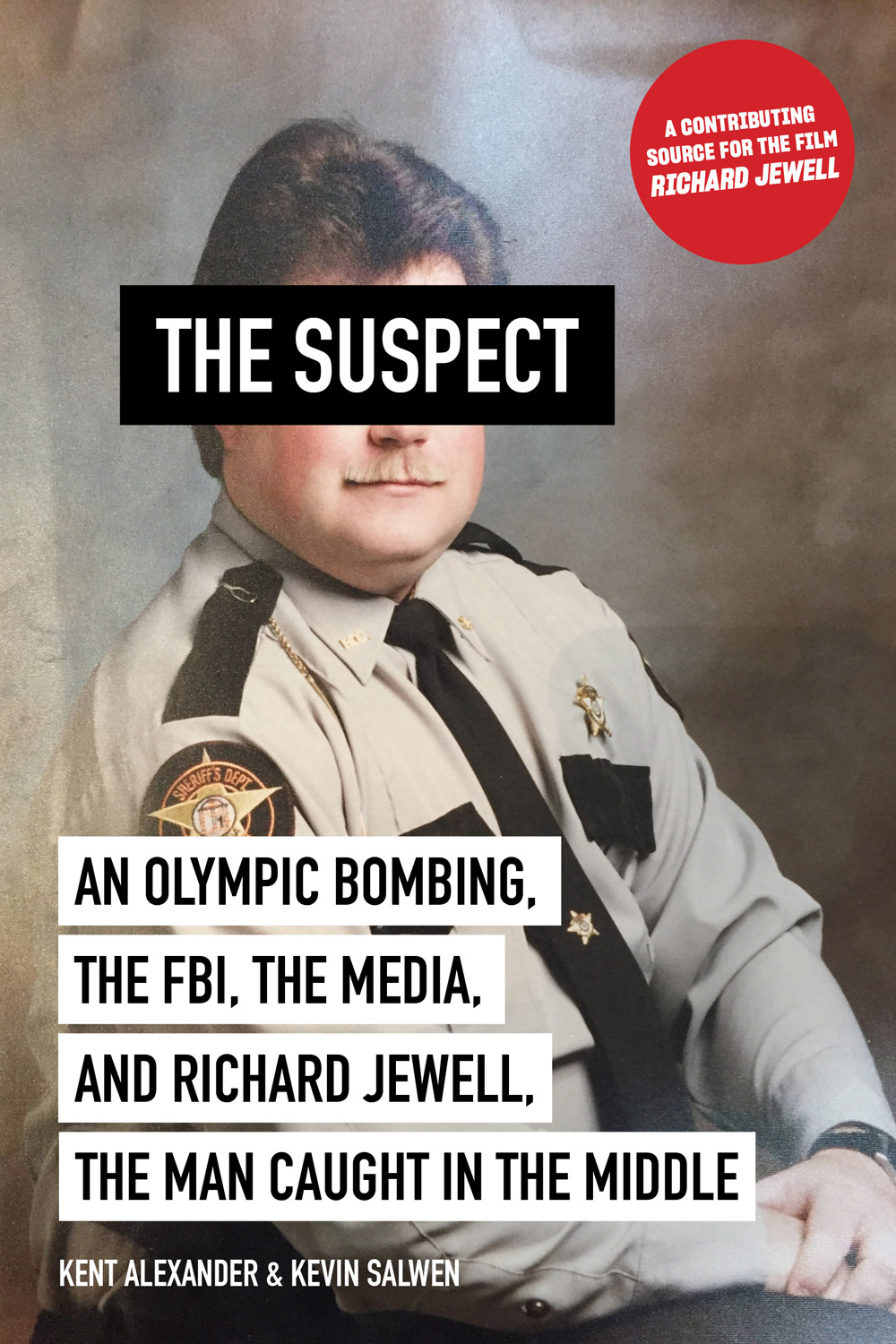

There are ironies within ironies at work within and around Eastwood’s film. For one thing, the movie, which at times reduces journalists to odious caricatures, is itself based on two pieces of remarkable journalism. One is a 1997 Vanity Fair story on Jewell written by Marie Brenner. If newspapers are the first draft of history, Brenner’s story was a refined and comprehensive second draft that focused on the toll that being outed as a suspect took on Jewell in the 88 days between the bombing and when Kent Alexander, then U.S. attorney for the northern district of Georgia, formally cleared Jewell’s name. The other piece of source material is The Suspect, a book published last month and co-authored by Alexander and Kevin Salwen, who in the 1990s was an Atlanta-based editor for the Wall Street Journal.

Photograph courtesy of Abrams

The Suspect draws in part on journals Alexander kept in the days after the bombing, which claimed the lives of two people but would have indisputably killed more but for Jewell, who spotted the suspicious backpack containing the nail bomb, alerted authorities, and helped widen the perimeter in the minutes before it exploded. The journal, Alexander told me, “was a good way to keep a continual record of what was happening in the investigation. I wasn’t doing it to write a book.”

Over the five years that Alexander and Salwen spent researching and writing the book, the journal, Alexander said, served “as a guide for where to go for the facts, rather than for the facts themselves.” Indeed, The Suspect is not at all a memoir—Alexander appears sporadically throughout the book and is identified in the third-person—but an exhaustively researched exploration into the collateral damage caused by the detonation of the bomb. In 2003, the fugitive Eric Rudolph was captured and confessed not only to the Olympic Park bombing but to three other bombings—two at abortion clinics and one at a lesbian bar in Atlanta. He is serving four consecutive life sentences in federal prison.

Alexander said he began doubting the likelihood that Jewell was the bomber not long after attention first focused on the security guard. “After a week or so, it became clear that there was a lot more exculpatory evidence than inculpatory evidence,” Alexander said. The job of a U.S. attorney is, ostensibly, to be the chief law enforcement officer in his or her respective district. The agencies—the FBI, say, or the ATF or the IRS—conduct the investigations while the U.S. attorney decides whether there’s sufficient evidence to bring a case to a grand jury.

In the days and weeks after the bombing, the FBI pursued its investigation into Jewell with a zeal and blinkered intensity that in retrospect feels more suited to a bumbling police state than to a country where due process is supposedly sacrosanct. On Tuesday, July 30, the same day that the AJC accurately named Jewell as a person of interest in the bombing, the FBI persuaded the security guard to accompany lead investigator Don Johnson to its headquarters to sit for an interview that would be used, Johnson told him, as a training video for first responders. It was an absurd lie, but Jewell, who’d worked briefly as a sheriff’s deputy and idolized law enforcement, went along. By then, Alexander and Salwen write in The Suspect, investigators were so convinced Jewell was the bomber that “a prison cell had been prepared that morning at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. If Jewell confessed, he would be transported directly to the maximum-security facility.”

The AJC’s scoop—“FBI suspects ‘hero’ guard may have planted bomb”—hit the streets just as Johnson was escorting Jewell to FBI headquarters. The media parked out in front of his apartment on Buford Highway. “I’m living a nightmare,” Jewell’s mother, Bobbi, would tell 60 Minutes. It was AJC reporter Kathy Scruggs who got the tip from a source that Jewell was the focus of the FBI probe. Scruggs was deposed multiple times in the subsequent libel litigation but never disclosed the name of her source. But Alexander and Salwen, in their book, do. It was Johnson, according to reporting done by the authors. (Johnson, in 2003, and Jewell, in 2007, both died of heart attacks. Scruggs, who struggled with depression and a reliance on prescription medications, died of an overdose in 2001.)

Which brings us to another irony: Scruggs, played by Olivia Wilde, is portrayed by name in Eastwood’s film. But the lead FBI agent is given the fictitious name Tom Shaw. After he divulges Jewell’s name, the Scruggs character offers to have sex with the agent. Wilde, herself the daughter of journalists (if you’re keeping track of ironies), has defended her portrayal of Scruggs, saying that it’s “interesting that when audiences recognize sexuality within a character, they immediately, when it’s a woman, allow it to define her, and I think we should stop doing that and allow for nuance.” Wilde is certainly on to something here, but what her comments have to do with the notion that Scruggs traded sex for a scoop—for which no evidence has ever emerged—is lost on me.

The portrayal of Scruggs rankled the AJC’s corporate parent, Cox Enterprises, which demanded that Warner Brothers, the production company, tack a disclaimer to the film. In its response, Warner Brothers said, “It is unfortunate and the ultimate irony that the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, having been a part of the rush to judgment of Richard Jewell, is now trying to malign our filmmakers and cast.”

Photograph courtesy of Abrams

Alexander and Salwen spent the days before and after the film’s release last week speaking around Atlanta, including to the Atlanta Press Club and the AJC.

“We ought to be having discussions about how newsrooms behave, then and now,” Salwen said. “[The Richard Jewell story] is a perfect case for that. I’ve had people come up to me and say, ‘This is a conversation you should be taking to every journalism school in America.’”

For his part, Alexander believes that investigators who feed leaks to reporters should be prosecuted. “There should be more criminal laws in place for anyone who divulges the name of a suspect in a case who’s not even charged,” he said.

Alexander, who left the U.S. attorney’s office in 1997, said when his and Salwen’s reporting confirmed the identity of Scruggs’s source, “I was just angry. I was shocked. I knew this guy, and I did not think it would be somebody I knew. I’m still flabbergasted. Every former agent who I’ve talked to said they’ve been shocked, and they had no idea.

“This idea that anyone would put Richard Jewell’s name out before the FBI was able to interview him was stunning to me. It cut completely against what the strategy was. When I saw the actual headline come out, I was at the FBI on the fourth floor and Richard Jewell was down the hall from me. It was just a throw-your-hands-up moment. How did this happen?”

As both men pointed out, the speed of public disclosures has only accelerated in the age of social media. Salwen mentioned the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, when social media identified the wrong suspect, and the Duke lacrosse case in 2006, when three players were falsely accused of rape. What needs to always be remembered, Alexander said, “is that there’s a human being at the end of every news story and criminal investigation.”

Said Salwen: “One of the most crucial lessons is that we really need to slow down and stop rushing to judgment. I mean that for the media, which can be under such pressure to break a story. But the other piece of the puzzle is that we in the public need to stop demanding immediate answers to questions that often aren’t answerable right now. The Richard Jewell case, coming before social media, is very much a social media story. Everyone wanted to know who did this, and the reality is once they felt like they had an answer, the confirmation bias just sprang to life. It’s a pretty dangerous thing. We all move on, but who gets left in the rubble but Richard Jewell? These are real human lives.”

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)