Photograph by Richard L. Eldredge

On Sunday, March 13, Atlanta’s 53rd mayor Sam Massell died at age 94, just two years after retiring from his 32-year stint as head of the Buckhead Coalition. In January 2020, Massell shocked the city by announcing his retirement at the annual meeting of the business-boosting nonprofit he helped found in 1988. In 2015, Massell had navigated the loss of Doris, his wife and life partner of 63 years, to Alzheimer’s. In 2016, he surprised friends and family alike by marrying longtime family friend and real estate business associate Sandra Gordy. After a half-century of seven-day work weeks, Massell was determined to slow down.

He had more than earned some time off.

From 1961 to 1969, Massell served as the president of the Board of Aldermen (now Atlanta City Council), later getting his title changed to Vice Mayor. In 1969, he ran for mayor and won, thanks to the support of the city’s growing Black population. Massell made history as the city’s first Jewish mayor. In 1974, he lost his bid for re-election when his Vice Mayor Maynard Jackson made history and won election to become the city’s first Black mayor, thanks to the overwhelming support of the same Black voters who put Massell into office.

In 1988, Massell returned to a high-profile position of power when he was named the head of the Buckhead Coalition, becoming Buckhead’s unofficial “mayor” and chief cheerleader. The charismatic Massell would work the room at countless business openings and receptions, giving out deer lapel pins to match his own—if you could tell him how Buckhead got its name. (Legend has it tavern owner Henry Irby once placed a large buck deer head on a post to attract attention to his business.)

I wore the pin Massell had given me decades earlier when I met him on February 24, 2020 in his 16th floor memorabilia- and photo-festooned office at the Buckhead Coalition. Tongue-in-cheek, Massell referred to the space as “ego alley,” but he remained proud of the photos behind his desk, posing with U.S. presidents Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George H.W. Bush, Richard Nixon, Lyndon Johnson, and Harry Truman.

Photograph by Richard L. Eldredge

Photograph by Richard L. Eldredge

After decades of stops and starts, Massell was pleased that in 2017, an official biography of his public life, Play It Again, Sam: The Notable Life Of Sam Massell, Atlanta’s First Minority Mayor, written by Land O’ Goshen author Charles McNair, was finally on bookshelves.

In what would be his final sit-down, career-spanning interview with Atlanta magazine, Massell discussed his many accomplishments, including his battles with his more conservative mayoral predecessor Ivan Allen, the anti-Semitism he faced, getting the city’s transformational MARTA mass transit train and bus system started in the 1970s, Georgia 400’s life-changing expansion into Buckhead in the 1990s, and what he hopes his legacy will be in Atlanta.

During lockdown in August 2020, I also enjoyed one final phone conversation with Massell to discuss his historic appointments of the city’s first out LGBTQ+ members to his mayor’s advisory board for the magazine’s Atlanta Pride at 50 issue. As we wrapped up our official business, I asked the freshly reformed workaholic how retirement was treating him.

“You know, as it turns out, I find myself most agreeable to it,” Massell said. “Each afternoon, around 5 or so, Sandra and I will fix ourselves an ice cold vodka martini and just relax, discussing the day’s events on the patio. Who knew I could enjoy such a thing? I heartily recommend it.”

One of the illuminating aspects of this new biography is that it highlights the many obstacles you overcame to become Atlanta’s first Jewish mayor. Your father told you, “No Jew could ever be elected to any city-wide office in Atlanta.” You proved him wrong. Do you think your election made it easier for other Jewish leaders seeking office amid the coming wave of diversity that our city has enjoyed?

I do, absolutely. It has made it easier and better for people to serve with confidence and to have the opportunity to prove their value while making a contribution. I love this city. Yes, my election helped Jewish people. Think about it, as we sit here, there’s a Jewish person running for president [Bernie Sanders] and his religion isn’t even referenced. I hope that means we’ve made progress. When I was running for mayor, I used to tell African American audiences that I would never be able to feel their disappointments and losses because I wasn’t Black. But as a Jew, I had a cross burned on my lawn. I had to bicycle past the Venetian Club where they’d hung a sign: “No Jews or Dogs Allowed.” In 1951, I ran for city council in [North Fulton County’s] Mountain Park, where the political bosses told me, “We don’t want no Jew on our council.” So I had experienced things my political opponents hadn’t. I understood how that pain can affect you.

Serving as vice mayor during Ivan Allen’s mayoral administration from 1962 to 1969, your liberalism butted heads on many occasions with Allen, who once ran for governor as a segregationist. Later as mayor, when Blacks began buying homes in the white neighborhood of Cascade Heights, you talked Allen out of building a literal wall to separate the Black community on Peyton Road from Cascade Heights. Later, he floated an idea for all so-called hippies living in Midtown to wear dog tags until you reminded him of the yellow Star of David badges the Nazis ordered Jews to wear during World War II. Many of your white male counterparts in city and business leadership did not share your commitment to social change and offering opportunities to people of color, women, and LGBTQ+ people. Why was it important for you to follow this more difficult path, a path that put you squarely at odds with Allen and others?

That’s an excellent question. I wish I had an excellent answer. Here’s what I can tell you: It’s a testament to my environment growing up. My family, we lived by those principles. I have to admit it was far from the political correctness of today, but still, it was far ahead of the hate that we saw coming from Birmingham and some of the other cities. When I attended Druid Hills school, which was a county school, my classmates came from a variety of backgrounds. The buses went out to dirt roads and picked up students in overalls. It also served a very affluent area. Druid Hills was a bit like the Buckhead of yesteryear. Some of my classmates arrived to school in chauffeur-driven limousines. We all played, worked, studied, and fought together. We never thought about who among us was rich or poor. The socioeconomics of it escaped us entirely. I never realized it until years later, that helped me a great deal.

And then, I met the right people. It made headlines when two successful Black professionals, A.T. Walden and Miles Amos, filed paperwork to serve on the White Democratic Executive Committee and the whites rejected them. They won their court case and the white members resigned. All but one, Margaret MacDougall, who went on to have a profound influence on me. She ended up chairing that committee. It became important for me to be a part of the American Jewish Committee, and I became vice president of the Anti-Defamation League. When I appointed the first woman to Atlanta City Council (because the charter allowed me to fill vacancies), I discovered a woman had not served in that capacity for 125 years. The other gentlemen on the council asked me, “Where is she going to go to the bathroom?” That was their big concern, rather than the notion that we were turning away half the population and their input and ideas. That struck me as, well, dumb.

Even today, I get myself into trouble with some of my peers when the subject of equal pay for women arises. My view is simple: to hell with giving women equal pay—in many instances, we ought to pay them more. Overall, they’re better educated, have more integrity, are more committed to the big picture, and very likely had to work twice or three times as hard to get where they are.

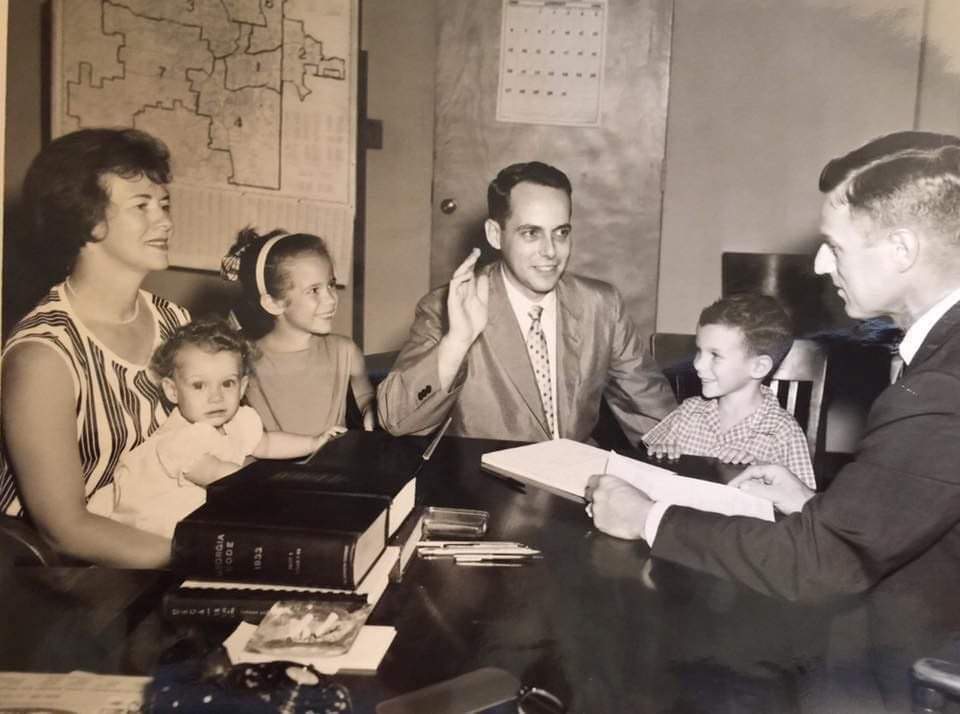

Photograph courtesy of Melanie Massell

You notably never made promises while running for city council or for mayor. I can’t think of a modern politician who could get away with that. How did you manage that and yet win the race for president of the Board of Altermen in 1961 and later, the mayor’s race in 1969?

I guess it goes back to a conversation I overheard one night after dinner between my grandfather and my father. I learned integrity from them. I was on the floor playing with my erector set or some such and listened as my grandfather, Sol Rubin (who had his own department store downtown on Peachtree), reacted to my father discussing a local politician. To make his point, my father said, “Well, at least he’s honest.” And Big Pop (which is what we called my grandfather) retorted, “Well, that’s nothing. Politicians are supposed to be honest.” It just stuck with me.

There are a couple of notable public exceptions to your adherence to honesty. One of those happened in April 1985 when you and other dignitaries were invited by the Coca-Cola Company to appear on a flatbed truck in front of the Coca-Cola building to sample a new product. What was your reaction when you put that bottle to your lips and tasted New Coke for the first time?

There were TV cameras pointed at us and a lot of fanfare and I was among the alleged celebrities present. It was terrible. I had to smile and wave, drink it and say, “this is wonderful” but it was godawful stuff.

Do you feel any sense of vindication now that New Coke is taught to prospective marketing students as a product launch disaster to avoid?

[laughs] No. I have eternal respect and dedication to the Coca-Cola Company. After all, Robert Woodruff gave me $3 million to build a public park in Buckhead, another $3 million to build a park on West Peachtree and Baker Street downtown, and $10 million to build Woodruff Park. I remain in a state of awe at what he and the company have done and continue to do for the city of Atlanta. We owe a debt of gratitude to the Coca-Cola Company.

Photograph courtesy of Melanie Massell

One night in the 1960s when Mayor Allen was out of town, you stepped in to host former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt at a dinner in her honor on her last night in town. As the party was breaking up you discovered, to your horror, that Mrs. Roosevelt had no Secret Service protection or security and was determined to drive herself to the airport at 11 o’clock at night. How did you manage to convince her to modify her travel plans?

Let’s get one thing straight. I never convinced Eleanor Roosevelt to do anything. I had admired both of the Roosevelts so much. I was in a tight spot. I just reached a compromise with her. I knew I wasn’t going to win the argument, and I also knew I couldn’t afford to lose it either. I just informed her that she was required to have some protection, whether she liked it or not. So we compromised. An Atlanta police officer would follow behind her to the airport.

Behind your desk here, you have a series of photographs of you with U.S. Presidents you’ve met. Can you discuss the story behind the photo of you and Harry S. Truman?

Back when I was president of the city council, former President Truman was flying through Atlanta on his way to Savannah. Mayor Allen was out of town. I learned he had a 90-minute layover between flights. This was on a Sunday, so I arranged to pick him up with the editor of Atlanta Journal and the chief of police. We drove him downtown to the Bank of Georgia building at Five Points downtown, a building that had floor to ceiling windows. We took him up to the [Top O’ Peachtree] restaurant on top of the building. I said, “We don’t have time to take you on a tour of the city, but at least you can see all of it from up here.” The owner came and opened up just for us. To be polite, he asked, “Mr. President, would you like a cocktail?” Without blinking, Truman replied, “You’re damn tootin’ I would!” He took a bourbon. On the way back, we were cutting it very close to his departure time. We’re speeding through East Point to get to the airport and Herbert Jenkins, [Atlanta’s then-police chief] is driving us and manages to get pulled over by a local cop. When the officer approached the car, Jenkins just rolled down the window, pointed in the back seat and yelled, “We’ve got the President of the United States with us!” and just sped off. We got him to the plane on time.

In the closing days of your 1969 mayoral campaign, there was scandal involving a police captain on your security detail accompanying your brother Howard on trips to small business owners asking for campaign donations. As we would say today, the optics of that weren’t good. When the story broke two days before the election, Mayor Allen called a press conference and urged you to withdraw from the race, stating you had “misused your position.” In return, you bought airtime on WSB-TV and told Atlantans, “Ivan Allen and his friends are the same men who don’t want me to sit in their clubs.” What persuaded you to do that?

The prejudice needed to be exposed. Part of that story that hasn’t been told is after I became mayor, those [private] clubs did offer me complimentary memberships. I turned them down. I said, “I didn’t qualify before I was mayor. I’m still Jewish.” I didn’t go to the press and make a story out of it, so it was never reported.

You won that election with 93 percent of the Black vote and 25 percent of the white vote. In your inaugural address in January 1970, you stated, “To those who are saying I will be paying a debt to [African Americans], let me answer they are correct . . . but not a debt resulting from election . . . a debt dating back over 100 years.” Why was it important to say that?

I wanted people to know the real Sam Massell. I had respect for Ivan Allen and his business success, but I did not have the same stature in the community or in the business world as Ivan and his team. Although he was not my opponent, we appeared in opposition many times. I just felt that I needed to make it very clear where I was coming from and what my sentiments were. Much later on, while she was the AJC editorial page editor, Cynthia Tucker referred to me in one of her editorials as a “moderate.” I sent her back a letter stating, “Don’t call me a moderate. I’m a liberal and proud of it.”

Photograph by Richard L. Eldredge

In your four years as Atlanta mayor, it’s almost like you hit the fast-forward button. Your administration got a lot done, including establishing MARTA, which, as Andrew Young states in his foreword in Play It Again, Sam, set Atlanta up as an international city, a city that would go on to host the Olympics in 1996, partly because of the transportation infrastructure you helped put into place. As you step away from public life, does MARTA remain one of your greatest achievements?

Overall, it is because it is both the brick and mortar of economic impact on the city as well as humanitarian in helping the disadvantaged and the transit-dependent. When you think about it, man’s fifth freedom [in addition to F.D.R.’s Four Freedoms of speech, worship, want, and fear] is mobility. Otherwise, you’re imprisoned in your own home. You can’t get to work, the shops, or the park. It was an endless discrimination we couldn’t afford. It was very important to bring that off. I’m also proud of appointing the first woman to city council in 125 years and appointing the first Black City of Atlanta department heads in the city’s history. Thanks to how the city charter was written back then, these were opportunities I could legally do as mayor.

Over the years, the two of us have discussed in detail how you got MARTA passed by getting residents on board to vote for the sales tax to pay for it. You went neighborhood by neighborhood with a small chalkboard in hand and did the math for them. But some voters remained unconvinced. So you rented a helicopter with a bullhorn and flew over clogged rush hour traffic, telling commuters below, “If you want out of this mess, vote YES.” Where in the world did you come up with that idea?

This being the Bible Belt, you know, they thought God was telling them what to do. I’m an idea man. We used helicopters again [in the late 1980s] when we were lobbying for Georgia 400 to come down from 285 to 85 to Buckhead, one of the first things we tackled here at the Buckhead Coalition. I took city councilmen up with me in the helicopter over the route so they could see what we were talking about and how few homes and trees would ultimately be affected by the new roadway. I can tell you something now that never made it into the press—one of the councilmen said he wouldn’t come unless he could bring his wife. I said okay. Well, she got airsick and threw up in the helicopter. No good deed goes unpunished. It turned out okay; I got his vote.

Photograph courtesy of Melanie Massell

Photograph courtesy of Melanie Massell

How does Sam Massell want to be remembered by the people of Atlanta?

One of the most important things is this—I was given the opportunity of managing the transformation of Atlanta’s city government from an all-white power structure to a predominantly Black city government. And I successfully executed it peacefully. The operative word is peacefully. We didn’t have riots, marches, or shootings. And that ultimately explains a lot of the other things I’ve been able to do because it meshed with that accomplishment. But if I had done just that, that’s pretty good. I’m happy with that. Ultimately, I hope I’m remembered as a native Atlantan who loved his city.

Services for Massell will be held at the Temple, 1589 Peachtree Street Northeast, on Wednesday, March 16 at 3 p.m., with a private family interment following. The Temple,

The funeral will be broadcast live on Zoom (Webinar ID: 856 6554 0682). In lieu of flowers, please consider donations to the Atlanta Humane Society, the Temple, and/or the Oakland Cemetery Foundation.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)