In 1911, Black educator and intellectual Booker T. Washington met Jewish businessman Julius Rosenwald at a fundraiser. The partnership forged that day—between the man who rose from slavery to found present-day Tuskegee University and the millionaire president of Sears, Roebuck, and Co.—would forever change the face of the South.

At the turn of the 20th century, Black public schools, where they existed at all, received a fraction of the funding afforded to white schools. Washington and Rosenwald bonded over their shared belief that education was the path to equality and progress and, over the next two decades, would orchestrate the construction of nearly 5,000 schoolhouses in 15 states. Rosenwald schools, as they would later be known, were the only providers of public education for more than 35,000 students in Georgia alone.

Labor economists from the Federal Reserve credit the program with narrowing the white-Black education gap in the South between the world wars. Educators in these buildings empowered Black children to become poets, Tuskegee Airmen, actors, and leaders and foot soldiers in the civil rights movement, some of whom were murdered for the work they did in and around these schools.

The building program ended in 1932, and knowledge of the Washington-Rosenwald partnership faded with the decades. But when writer and photographer Andrew Feiler, a fifth-generation Jewish Georgian, learned about the schools in 2015, he knew they were something to document and preserve. Over the next few years, he drove 25,000 miles, interviewing and photographing for A Better Life for Their Children. He found that, of the nearly 5,000 Rosenwald schools constructed, 500 remain, only half of which have been restored. Feiler hopes to bring attention to the remaining, at-risk schoolhouses and the often-overlooked moments in U.S. history with which they intersect, like the Tuskegee syphilis study and the Trail of Tears.

Feiler’s call comes at a time when, he says, Americans need to be reminded of their capacity to work together toward positive change—a sentiment reflected in the book’s foreword, excerpted here, written by late Rosenwald alumnus and congressman John Lewis.

Excerpt

Materials from A Better Life for Their Children. Excerpt courtesy of the University of Georgia Press. Photographs courtesy of Andrew Feiler.

“My parents would describe education in almost mythical terms, that it offered the keys to the kingdom of America, that it offered the keys to a better life and to the opportunity so long denied our race. My parents had not gone far in school themselves, and they wanted more for me. But when there was work to be done in the fields, that came first. Farming season and the school year would overlap at times, and when they did, I was expected to stay home and help to pick the cotton or pull the corn or gather the peanuts.

I was not the only one to have to work in the fields, of course. This was true for almost every child in our school. It was a Southern tradition, just part of the way of life, that a Black child’s school year was dictated by the farm rhythms of planting and harvesting.

[ . . . ] We were striving to catch up, not just with ourselves, but with the children in other schools who did not have to work in their families’ fields to survive. I did not know about children like that when I began elementary school, but I knew about them by the time I finished. I knew that the names written in the fronts of our raggedy secondhand textbooks were white children’s names and that those books had been new when they had belonged to them. And I knew ever more clearly that education was the way out and the way up.

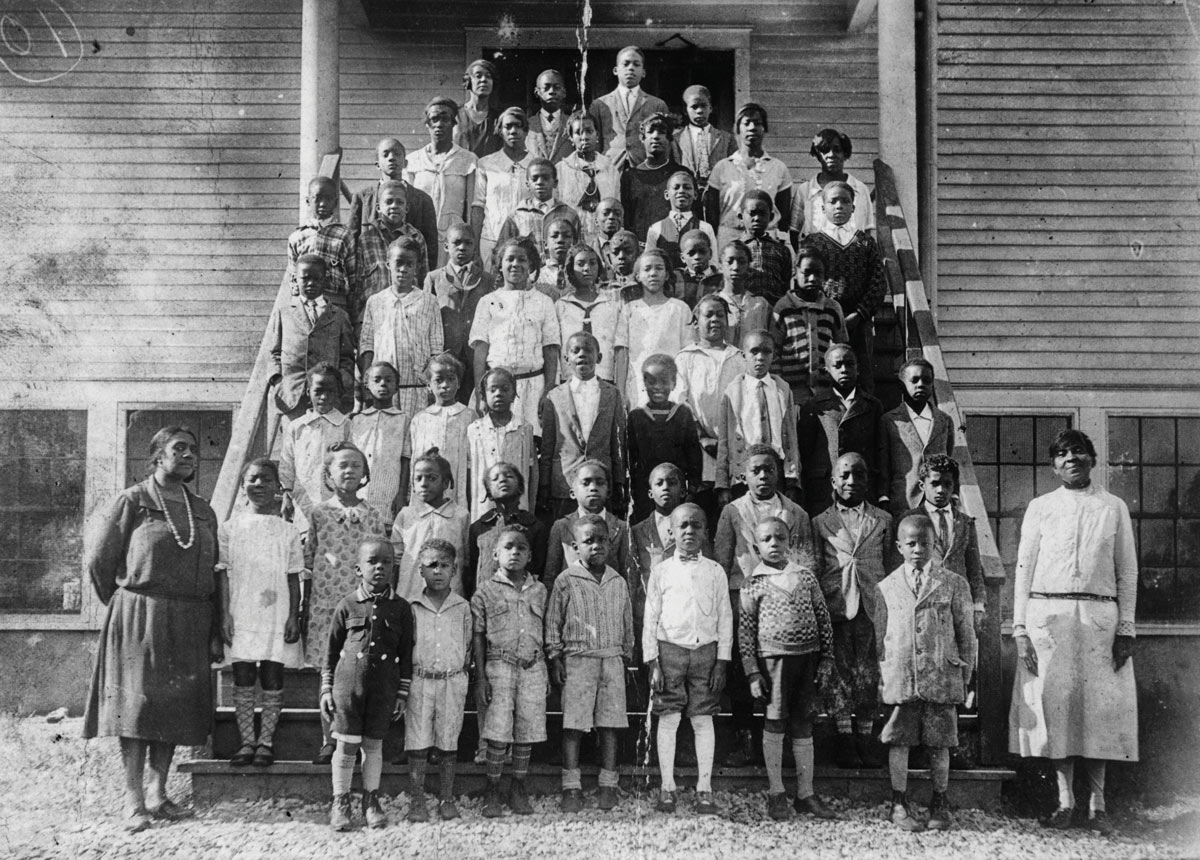

Feiler’s photographs and stories bring us into the heart of the passion for education in Black communities. The passion of teachers who taught multiple grades and dozens of students in a single classroom. The passion of parents and neighbors who helped to raise the money to build our schools and then each year continued to reach deep to purchase school supplies. The passions of students like me who craved learning, worked hard, and read as many books as we could put our hands on.

Just as important, Feiler brings us into the inspiring partnership of Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington, who together harnessed these deeply held passions in African American communities to bring a better education to generations of students like me. Rosenwald and Washington reached across divides of race, religion, and region. Their partnership demonstrates that concerted action can make America better and the world better.

Education is the cornerstone of democracy. Education gives us the skills and the know-how to build a better world. Informed and engaged citizens hold the power—through their vote and through their actions—to make our world work better for all. America is made better each time one of us sees something that is not right, not fair, not just, and has the courage to stand up, to speak up, and to find a way to get in the way.”

Q&A with Andrew Feiler

How did the foreword by John Lewis come about?

I’m a fifth-generation Georgian. I grew up in Savannah. I left the South after high school and went bouncing around the world for some period of time. I’ve been back in Atlanta now for more than 25 years, and for that entire time, I have lived in the Fifth Congressional District. I was a constituent of Congressman Lewis’s for 25 years. It was clear to me from the beginning that the perfect person to write the introduction to this book would be Congressman Lewis. I said, What I want you to do is what only you can do: Bring me into that classroom. What was it like to go to school there? What role did education play in your life? Talk about the connection between education and democracy. He said, I can do that.

Between WWI and WWII, the Black-white education gap narrowed significantly, thanks, in large part, to Rosenwald schools. The same schools also helped fuel the civil rights movement, educating many of its leaders and foot soldiers. How can a movement so transformative be so easily lost to history?

There are two answers to that question. Number one, Julius Rosenwald was modest. He did not name these schools “Rosenwald schools.” When Congressman John Lewis was a student, he didn’t know he was at a Rosenwald school; he knew he was at a school. Brent Leggs—who runs the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund at the National Trust for Historic Preservation and wrote the afterword to my book—studied Rosenwald schools and found out that both of his parents went to Rosenwald schools. They didn’t know. After my talk at the Atlanta History Center, a woman thanked me for the conversation this sparked within her family. Some of her relatives went to Rosenwald schools, and they didn’t know until my book prompted that conversation.

Another piece of it is this: It’s fashionable in philanthropy today to mandate funds be given away either in the lifetime of the benefactor or within a certain number of years after the benefactor’s death. Rosenwald was the first major philanthropist to do this. He believed that the generation that helped create the wealth should benefit from that wealth. He mandated that all the funds be given away within 25 years of his death, and that’s one of the reasons his name is less well known than some of his philanthropic contemporaries with surviving foundations, like Carnegie, Ford, and Rockefeller.

“Separate but equal” schools are recent enough in U.S. history that you were able to speak with teachers who worked at them. What was that like?

Teachers played an unheralded role in the civil rights movement. Vanessa Siddle Walker, who is a professor at Emory, has a book called The Lost Education of Horace Tate, in which she talks about the role of teachers in Black schools in the segregated South. These teachers fueled the civil rights movement [with] the promise of equality and the power of democracy. When we think about Brown v. Board of Education and the seminal role that it played in desegregating education, we think about Thurgood Marshall and his team. It was teachers who gathered data and sent it to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. It was that data that helped Thurgood Marshall and his team make the case that “separate but equal” was inherently unequal. When I went to the Bay Springs School in Mississippi and sat with Ellie Dahmer, she specifically talked about that aspect of her role in the civil rights movement, of actively being part of the teachers association that was gathering that data. These teachers were part of the movement.

Is institutionalized segregation a thing of the past?

Systemic racism remains a central issue in America. Congressman John Lewis would say, “Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month, or a year—it is the struggle of a lifetime.” He was deeply optimistic about America. So was Julius Rosenwald. So was Booker T. Washington. They understood change was the work of a lifetime, and they made that long-term view their life’s work. Part of this program was reaching out to the Black communities to say, We want you to be a partner in your progress. Those communities shared that optimism and long-term view: They were building a better life for their children.

How did you choose which stories would be featured in this book?

The exteriors tell an architectural narrative—[from] one-teacher schools to three-teacher schools. [They started with] small, white-clapboard structures. At the end of the program, they were building one-, two-, and three-story red-brick buildings. I found schools that were connected to the Trail of Tears, the Great Migration, the Tuskegee syphilis study, Brown v. Board of Education. Each of those becomes important to weaving the Rosenwald schools into the broader fabric of America. It was a tapestry: There’s all these threads, and there comes a point where it comes together and it feels complete.

You traveled 25,000 miles across 15 states to visit 105 schools. What kind of car do you drive and how did you keep yourself entertained?

I first heard of the Rosenwald schools in 2015. I started down the path of researching, but I had to get my first book [Without Regard to Sex, Race, or Color, 2015] out the door. It wasn’t until the beginning of 2016 that I started shooting this work. The museum exhibition of my first book traveled four and a half years. I would load up [the exhibition] into the back of my wife’s SUV. It was going to the International Civil Rights Center and Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina, so I researched Rosenwald schools in North Carolina, and I would take these back roads to Greensboro and shoot Rosenwald schools all the way up. I would shoot Rosenwald schools all the way home. Four months later, I would go to take the exhibition down, and I would do this all over again. I was moving my exhibition across the South, North Carolina to South Carolina to New Orleans to Memphis.

What I mostly listened to [during] those 25,000 miles was audiobooks related to civil rights history. There was this extraordinary complement to this journey: I am out in the process of telling this central but hidden history related to civil rights while I am immersing myself in the details of civil rights history. Carlotta Walls LaNier was a member of the Little Rock Nine. Her portrait appears in my book. I listened to her memoir of her involvement at Little Rock Central High School. I listened to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s book on the history of the Harlem Renaissance. I listened to a book on Dr. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

Of the original 4,978 Rosenwald schools, about 500 survive today, and only half of those have been restored. Why is it important to preserve these spaces?

We are at a moment in American history where we are especially aware of our need to tell a diverse American history, the full American history. There are 95,000 places listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Only 2 percent are connected to telling the narrative of Black history. We have to preserve the places and spaces that help tell these essential stories. There’s this extraordinary line that runs through many of the people whose portraits I share in this book: Many of these folks that I met on this journey were students in Rosenwald schools. They become teachers and then they become the people in their community leading efforts to preserve these structures. Student becomes teacher becomes keeper of the flame of history and memory.

Rosenwald and Washington came together to solve a crisis of their time. What similar-in-scope crisis does the United States face today?

If you’re looking at the legacy of Rosenwald and Washington, their work highlights an extremely important theme in American history: Education is the backbone of the American dream. This is a theme that has deep roots in America, from the commitment to public education, which predates the United States, to land grant colleges and the creation of historically Black colleges, to Rosenwald schools in the early part of the 20th century, to the educational provisions of the GI Bill, to Brown v. Board of Education. Today, we are talking about college affordability, college access, the drag of college debt. Education has been the backbone of the American dream for hundreds of years. Yet today, that is a dream at risk. When you think about this long-term perspective, this long-ball view of Rosenwald and Washington, they would come back to this central theme of education. We have to continue to protect the essential role that education has played as the on-ramp to the American middle class.

Do you ever think about what the South might be like if Rosenwald and Washington had never met?

I think it’s more important to simply celebrate the fact that they did. They meet in 1911, before the Great Migration. Ninety percent of African Americans live in the South, and public schools for African Americans at the time are mostly shacks with a fraction of the funding afforded to the education of white children. Many jurisdictions do not even have public schools. It was not just building 4,978 schools; it was building 4,978 schools against a backdrop where education for African Americans was systemically deprived.

Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington not only formed a civic relationship, they developed a friendship—one of the earliest collaborations between Blacks and Jews for the cause of civil rights. There’s a direct connection between the partnership of Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington to the relationship between Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Dr. King, who marched together, to what just happened in Georgia: For months, Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock campaigned together across the state and built a political alignment and a friendship. And so, Georgia sent its first Jewish senator and its first African American senator to the United States Senate. The Ossoff-Warnock alliance stands on the shoulders of the relationship of Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington.

This article appears in our July 2021 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)