Illustration by Kyutae Lee

In 1995, Cassandra King was a 50-year-old preacher’s wife on the brink of divorce and an English teacher at the University of Montevallo in Alabama. She was eagerly awaiting the publication of her debut novel, Making Waves. At a literary conference party in Birmingham, she met Pat Conroy, the larger-than-life author of The Prince of Tides, who was there to receive an award. They bonded at the refreshment table, and a two-year telephone friendship ensued. They eventually married in 1998. First in Pat’s home on Fripp Island, South Carolina, and later in the home they bought in Beaufort, South Carolina, the couple lived together and wrote their books until Pat’s death from pancreatic cancer in 2016.

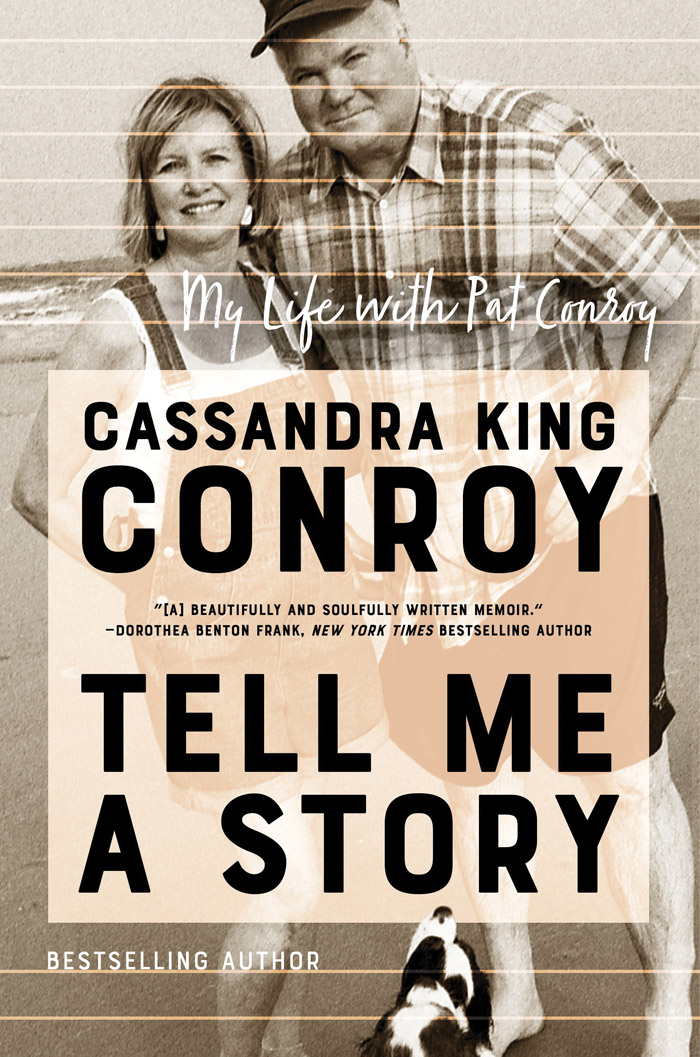

Tell Me a Story: My Life with Pat Conroy is Cassandra’s new memoir about finding love in middle age with a literary giant of the South, an Atlanta native who, until then, had led a tumultuous life. Together, they found peace and an easy companionship that provided a foundation for the prolific output of novels and memoirs that followed. Cassandra spoke with us from her home in Beaufort about the 21 years she spent getting to know and love Pat Conroy.

In this excerpt from Tell Me a Story, Cassandra King Conroy recalls when she and Pat had recently moved from Fripp Island, South Carolina, to their new home in Beaufort, South Carolina. One day, they decided to explore their new neighborhood by taking their motorboat, the Grasshopper, out for a spin.

In this excerpt from Tell Me a Story, Cassandra King Conroy recalls when she and Pat had recently moved from Fripp Island, South Carolina, to their new home in Beaufort, South Carolina. One day, they decided to explore their new neighborhood by taking their motorboat, the Grasshopper, out for a spin.

Once Pat and I got settled in, we decided to celebrate. “Let’s take the boat out at sunset,” Pat proposed. “I want to show you Battery Creek.”

“Just us?” I tried not to sound skeptical. The Grasshopper was now tied to our very own dock, but Pat and I had wondered if the two of us would be able to take it out alone. As we often lamented, we were old coots now, in our mid-60s, and not as dexterous as we once were.

“If we can’t do it,” Pat warned, “no need for us to have a boat.” It was an effective threat. I loved the Grasshopper and would have even if it never moved from the dock. “I’ll pack us a picnic,” I said.

Late afternoon, I carried chilled champagne in a cooler as we walked down to the dock. A few steps ahead and carrying the picnic basket, Pat stopped, and I almost ran into him. “You’re gonna love this, bird woman,” he said with a grin.

I looked up to see a great blue heron perched on one of the tall pier-pilings by the boat and gasped in delight. Another bonus of the new house: the abundance of sea birds. Even while trying to keep my balance as I climbed on board, I kept my eyes on the heron. Of all the birds, the great blue was a special favorite of mine and Pat’s. To my astonishment, the heron not only stayed put but also seemed to be eyeing me back. “It’s a sign,” I told Pat in a hushed tone.

Pat snorted. “Could’ve fooled me,” he said as he too climbed on board. “Looks like a bird to me.”

When he got behind the wheel, Pat turned his head my way, eyebrows raised. I sat perched on one of the cushioned seats, looking around blissfully as I awaited our maiden voyage into our new life. “Ah, sweetheart? I need a second mate here.”

I looked at him puzzled before it hit me what he meant. I jumped up red-faced, climbed off the boat quickly, untied us from the posts, then jumped back in. Balanced on the side of the boat, I stretched out my leg to give us a push away from the dock. The motor purred, the Grasshopper lunged, and off we went.

Pat steered the boat deftly through the steel-blue, rippling waterways edged in marsh as I perched on a cushion in the strong salty breeze and took it all in. I was enchanted, entranced, spellbound by the marshes lining the creek, the earthy smell of pluff mud, the foam-tipped wake created as the boat parted the silvery waters. Soon, we lost sight of the house. Finding the most isolated spot near a low-hanging oak on the bank, Pat dropped anchor so we could enjoy the sunset. There, the boat swayed back and forth, the only sound the swishing slap of waves against its sides.

Neither of us said a word as we reveled in the glory of the place we’d landed. As the sun disappeared into the marsh, the ripples of the slowly moving creek went from soft blue to deep gold to burnished pink. Darkness fell, but neither of us could move, or break the silence. I had no doubt we were thinking the same thing: This is as close to heaven as either of us sinners might ever get.

In the afterglow of sunset, Pat opened the champagne. We toasted our good fortune at living in one of the most beautiful places on earth. I pulled out the picnic basket, and we feasted on deviled eggs and boiled shrimp. Our picnic had been a simple one and hadn’t taken long, but darkness crept in faster than we expected. “Guess we’d best start back,” Pat said as he reluctantly pulled himself up to return to the wheel.

It was only when Pat steered us away from the embankment that we discovered the boat lights weren’t working. Our moods shifted quickly. The night was black as sin, and there we were, two old codgers who had no business staying out so late, on a dark river with only a quarter moon to lead us home. We dared not look at each other in case our apprehension turned to fear. I climbed onto the bow to see if the meager glow from our flashlight could guide the way. And it might have, had we thought to check the batteries before we left. There was nothing to do but creep along through the black waters and pray we wouldn’t hit a sandbar. Now that darkness had fallen, the warmth of the day had faded as well. From my perch on the bow of the boat, I shivered violently in the strong night wind.

When the lights of Beaufort came into view, I turned to Pat in alarm. Not only had we passed our dock; unfamiliar in the darkness, we had come way too far. We were on the Beaufort River, not Battery Creek. Before I could suggest that we dock in Beaufort and call someone to come get us, Pat had turned the boat around. I kept telling myself there was no need to panic.

With the quarter moon and the lights of Beaufort now at our back, Pat steered the boat through increasing darkness to retrace his steps. But my fear increased when I saw that all the docks we approached looked exactly alike. How would we ever find ours? Then, we rounded a bend, and I saw a familiar sight in the distance. My heart pounding, I yelled out, “It’s our dock, Pat! Pull in.”

And the great blue heron was there waiting for us, I swear he was. I saw him plain as day, perched exactly as he had been when we first spotted him on the piling. As we neared the dock, he lifted his magnificent wings and flew off, a shadow etched in the darkness of the night. It’s not possible, Pat scoffed when I told him how I recognized our dock. We were gone too long. I only imagined that the heron was waiting for us to return, he said. But I knew better. The great blue heron had stayed to guide us home.

Q+A with Cassandra King Conroy

by Suzanne Van Atten

Pat has been gone for more than three years now. How are you coping with your grief?

I keep thinking, Okay, one of these days, this is going to get better. I never want to tell recent widows, but it’s been three years since Pat’s died, and it seems like yesterday. I think maybe it’s because I’m still here, where he was. I see him walk in the house. I see him where he would usually be waiting. He would come down the stairs to greet me when I’d been out of town, or he’d be back in his room, and I’d stick my head in to tell him I was back. I see him everywhere. We have this beautiful creek here, and it looks like the cover of a Pat Conroy novel. Every day, there are reminders.

When you set out to write your memoir, did you intend it to be a love story about middle-aged romance?

I knew there would be a little bit of a different angle because Pat and I were in the same career. But that’s what I really wanted—for it to be about finding late-in-life romance when you least expect it.

In the book, you talk about your first date when you and Pat exchanged stories of your suicide attempts. How did that come about?

Yeah. [Pause] Bad way to bond, isn’t it? [Laughter] I think I was trying to say to him that I understood because I’d been there. But Pat was the kind of person who would just draw out your secrets. He had a gift for it. He was so truly interested in people’s stories. That’s why I never doubted what the title of this book would be. That was just Pat. When he met someone, he wanted to know their story. And I think that’s how it started between us. We were telling each other our stories.

In both his literature and his life, Pat portrayed knights in shining armor saving damsels in distress, but you seem to have saved him. What made you two click?

I have a laid-back personality. I don’t like a lot of drama. And I’m not real social. At that time in his life when we met . . . he needed peace and quiet and someone who’s less prone to conflict. We just came along at the right time.

Do you ever wish you had met Pat sooner?

I wish we’d had more time together, but I think we met exactly at the point in our lives when we were supposed to meet. I teased him about it. I don’t know that I would have put up with him back then. I probably would have knocked him out and thrown him in the creek.

You paint a picture of a happy marriage. What was your secret?

I really think that because of past experience—he’d had two previous marriages, and some difficulties with the second one, and I’d had a lot of difficulties with mine as well—we said, Let’s don’t repeat some of these things. Let’s be better to each other. Let’s be kinder. Let’s see if we can do things differently. I think that had a lot to do with it.

Did it help that you were both writers?

It’s not easy to live with a writer or, I imagine, any other artist like that, because we live in our heads so much. As a writer, you spend so much time in your own little world by necessity, you shut other people out. That is difficult for a relationship. At that stage in our lives, I think it worked for us partly because we were both writers, and we understood what writers need and what they need from each other, what they need from a partner.

Pat mentored countless writers in his lifetime. Was he a mentor to you?

He certainly was. He helped me not so much with my writing as he did with professional tips like, always make sure you get to know the booksellers when you go out. And don’t read your reviews. But, on the other hand, we would talk sometimes about how it was coming. I’d say, “Ah, I’m kind of stuck in this chapter,” and he might recount something.

Pat would tell a story over and over. So often, somebody would say to me, “Oh! I heard your husband talk, and he told that sweet story about you leaving a chapter on his pillow, and he read it and got it back to you.” And I’d always think, Yeah, that was just a few weeks after we got married, and I don’t think he’s read anything since.

Did you help him with his work?

As Pat got older, you could barely read his handwriting, and he’s always written everything [by hand], so he had to have someone type it for him. I would have to go over his handwritten manuscript and mark it up before it got to whoever was doing the typing. Pat had a tendency to write one long sentence after another, maybe connect them with ‘and.’ And I’d mark out ‘and,’ put in a period. So, every once in a while, the old English teacher in me would kick in.

What’s next for you?

When Pat got sick, I’d written about five chapters of a book that he had encouraged me to write. I was raised on a family farm, and I’m passionate about that disappearing landscape. There will come a time when nobody can say, “I was raised on a family farm,” because the family farm will no longer be sustainable. I’m trying to take that idea and find the best way to explore issues and ideas through fictionalizing it and making it into a story. It’s about a woman who—like so many people I’ve talked to—was raised on the farm and couldn’t wait to get out of the sticks, go out in the great big world, and find her fortune. And, so many times, they’re drawn back to where they started.

You were born in Alabama. Are you drawn back to where you started, or do you plan to stay in Beaufort, South Carolina?

I love Beaufort. I’ve made a home here. I have wonderful friends, and now, there’s the Pat Conroy Literary Center. Yeah, I’ll be here. I’m not going anywhere.

Questions and answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.

This article appears in our December 2019 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)