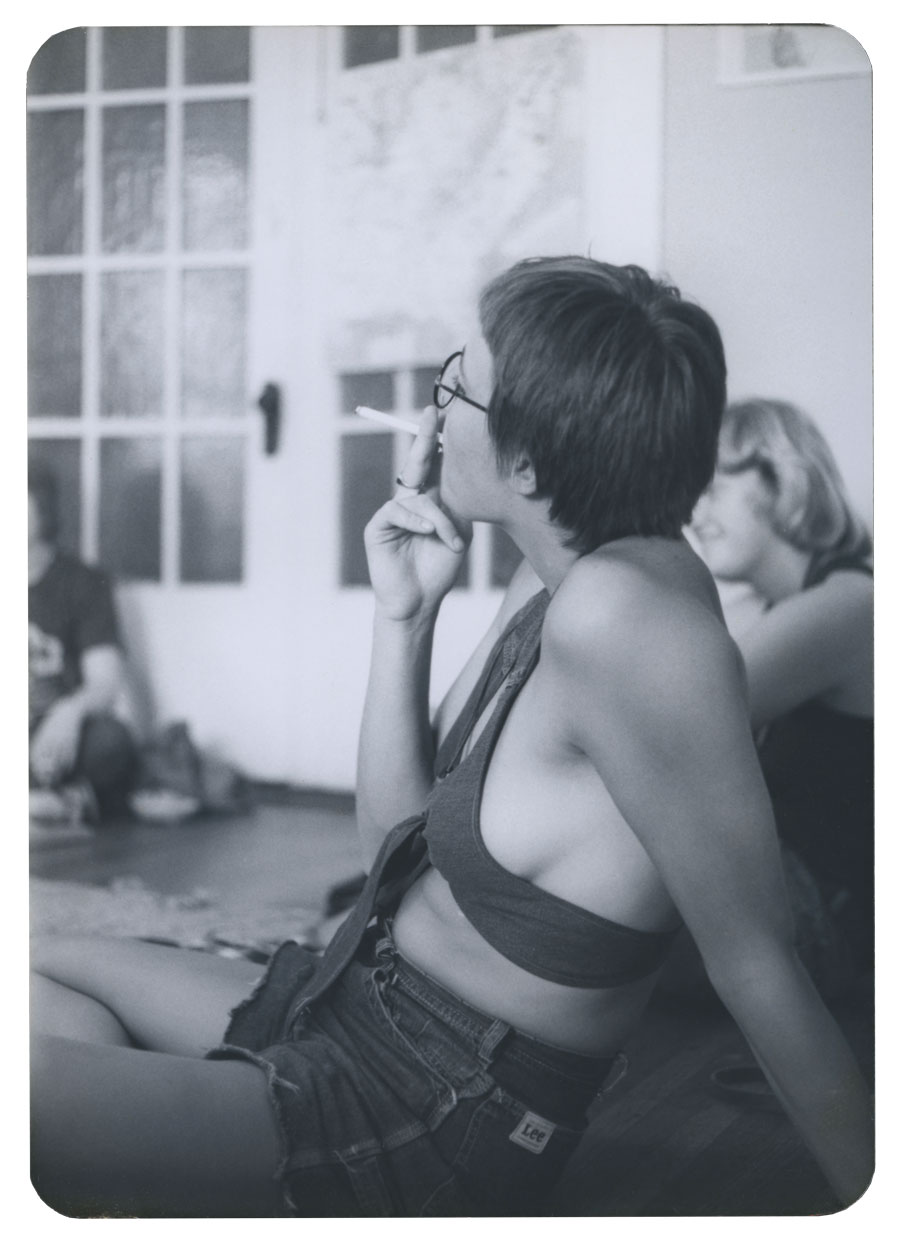

Photograph courtesy of Lorraine Fontana

If you happened, one day in June 1972, to be strolling past a shabby craftsman in Little Five Points, you might have caught the first murmurs of a revolution. Gathered inside was a small group of gay women, all drawn to the radical politics then swirling around the neighborhood but sidelined by the very organizations they’d come to support. Vicki Gabriner, who was there that day, later wrote, “Atlanta’s Women’s Liberation was too straight and the Gay Liberation Front was too male.” They needed, as attendee Diana Kaye put it, “an organization for dykes.” Thus was born the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance, better known as ALFA. Evoking the first letter of the Greek alphabet, the acronym signaled the group’s goal: an explicit reordering of a rigid gender hierarchy that was beginning to crack all over the world.

The ALFA women, who will gather this June to celebrate the 50th anniversary of their launch, immediately got to work growing the fledgling organization. “We are a political action group of gay sisters,” they announced in the Great Speckled Bird, Atlanta’s premier alternative newspaper at the time. Several early members, living communally on Mansfield Avenue, offered their home as command central; the group later established its permanent base in a house on McLendon. ALFA set up an answering machine to catch calls from potential members, while a dedicated PO box attracted mail from women all over the Southeast, many living closeted in rural towns, never dreaming it might be possible to live as an out gay woman. ALFA circulated a newsletter, Atalanta, that drew in yet more members. Women often arrived on the group’s doorstep having heard only that there was a lesbian group somewhere in Atlanta.

Photograph courtesy of Lorraine Fontana

Photograph courtesy of Lorraine Fontana

Elaine Kolb moved south from Buffalo, New York, in 1971, after meeting several women from Atlanta while in the Venceremos Brigade, a communist project that sent young leftists to Cuba for work-exchange programs. “I got on a Greyhound bus for Atlanta,” she told me, “found a phonebook, and looked up the Great Speckled Bird. I figured, it’s a bunch of old hippies—somebody will let me sleep on their couch until I can find the women I’m looking for.” Kolb became an early member of WomanSong, ALFA’s musical and theater group; along with the Red Dyke Theater, it performed politically driven art around the city, including some of the first women-led drag shows. In the ferment of the era, art became a revolutionary tool of self-expression: A woman in leather chaps and a mustache was not mere entertainment but a vision of another world.

ALFA had no presidents or secretaries. Its members disavowed hierarchy. Instead, they organized committees and led consciousness-raising sessions—the salons of the New Left—where women sprawled across the dilapidated front porch discussing feminism and racism. They joined early Pride parades, back when more people gathered to gawk at the drag queens than to march for gay rights, and protested homophobic newspaper coverage and Anita Bryant’s antigay tirades.

ALFA’s biggest political moment arrived in 1973, when feminist organizations, lobbying state governments to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, pushed aside lesbians for fear of alienating conservative women. Undeterred, ALFA partnered with the Socialist Workers Party to form Georgians for the ERA—which, in 1974, would lead the largest women’s rights demonstration in the city’s history.

Key to ALFA’s growth was its legendary softball teams: The group fielded its first team, the ALFA Omegas, in 1974, in a women’s league where they were the only out lesbians, astounding—and intriguing—closeted players on other teams. “It was a very good way to draw new members,” ALFA member Lorraine Fontana remembered. As word spread, women signed up in droves, and ALFA organized two more teams.

Softball proved ideal as an organizing tool: As Vicki Gabriner wrote in a 1976 article for the feminist journal Quest, “Come Out Slugging!,” the game drew in queer women across class and race more effectively than politics alone, and provided a sense of community that previously existed only behind closed doors. For many working-class lesbians who felt alienated by, or simply uninterested in, the gay rights movement and its college-educated leadership, softball was just a fun way to flirt with girls in broad daylight—a tiny revolution all on its own.

Photograph courtesy of Lorraine Fontana

ALFA welcomed softball players of any ability, just as it welcomed gay women of any persuasion: As member Elizabeth Knowlton put it in a 1999 interview, “You don’t have to pull out your lesbian ID card!” That inclusivity set it apart from separatist groups of the era, who declared lesbianism a political identity in opposition to male supremacy. C., one of the few Black women in the group, was reluctant to move into the ALFA house after her experience with such a community in North Carolina, where she’d moved into a lesbian house with a partner who was pregnant; when the baby turned out to be a boy, members of the house evicted them all. “You could say I had a tumultuous orientation into feminism,” she told me. (C. keeps a low profile these days and asked that we not use her full name.)

To her surprise, C. found a genuine home in ALFA—and, having excelled at softball as a kid, became the Omegas’ star player and team manager. But while the white women in ALFA welcomed her, she struggled to meet other Black lesbians: Atlanta’s de facto segregation limited social overlap, and Black lesbians had few spaces where they felt safe to congregate, leaving them at the margins of lesbian and feminist groups. C. and her ALFA comrade Lorraine Fontana became a couple and moved to Los Angeles, where C. founded a new group, Lesbians of Color, and a softball team, sponsored by the legendary Black lesbian club owner Jewel Thais-Williams. “Everything worked out beautifully,” C. said.

ALFA folded in 1994. Most original founders had moved on, and membership was dwindling. It left as it had come, with a matter-of-fact announcement in a newsletter: “After 22 years and the record as the longest surviving lesbian organization (that we know of), the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance has faded away.” Thanks to Elizabeth Knowlton, the group’s meticulous librarian, a fulsome collection of ALFA’s papers is archived at Duke University. At the group’s virtual reunion in June, a series of panel speakers will reflect on ALFA’s history and legacy, commemorating the extraordinary, ordinary story of a group of women who wedged open the door to liberation just a little bit further.

Elaine Kolb lives in Connecticut now, where she’s still active in leftist causes, a self-described “fat old ruddy white dyke.” She read aloud to me the lyrics of the theme song she wrote for WomanSong many years ago: “They told us that it was a sin, they told us we were wrong / But they never told us about the joy of singing a woman’s song.”

This article appears in our June 2022 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)