Picture the mutating beast that is metro Atlanta. Now zoom in to the center, between downtown and Buckhead, to the area bounded by Piedmont Park to the east, the Connector to the west, Pine Street to the south, and the Amtrak Peachtree Station to the north. This is the Midtown Improvement District, a 1.2-square-mile section of the city in perpetual reinvention. In 2000 the district counted 5,400 residences; that’s expected to quintuple. Waves of baby boomers and millennials are filling glassy apartment towers. Eight of Atlanta’s top 10 law firms are here. And the district’s base of 65,000 jobs is expected to swell by thousands more once companies such as Kaiser Permanente and NCR Corporation set up operations here. Now zoom in further to the curved spine of Peachtree running north from 10th Street. In the past century and a half, this has been, at various times, wilderness, crime-ridden hellhole, regal neighborhood, thriving commercial center, counterculture enclave, crime-ridden hellhole again, and now a desirable, expensive, urbanizing community in search of a centralized gathering place.

Now focus on the point where Peachtree meets 14th Street, which has the potential, in the eyes of developers, to become the “Main and Main” intersection Atlanta lacks. These builders and their lending partners hope to capitalize on a construction boom to transform this former geographical afterthought into a combination of epicenter and living room—a beating heart where culture and commerce converge.

It was here, 50 years ago, that a maverick former dairy producer from South Carolina leaped into Atlanta real estate and altered Midtown’s DNA, building the Southeast’s first mixed-use development, Colony Square. In a way, this pioneering “micropolis” was three decades ahead of its time, debuting a live-work-play concept long before smaller versions popped up from Brookhaven to Buford. But Colony Square stagnated as the rest of Midtown embraced cosmopolitanism and climbed skyward, literally casting shadows on this architectural melange of offices, condos, hotel rooms, and a tired and glass-topped food court. A movement Colony Square helped birth has now left it in the dust.

At this corner, on a sunny spring day, Mark Toro is talking above the hiss and groan of MARTA buses about a renaissance at 14th and Peachtree—what’s become the densest intersection, in terms of daytime working population, in the Southeast. Toro is the outspoken, debonair, MARTA-riding managing partner of North American Properties, the Cincinnati-based developer that bought Colony Square last November for $166 million. Under Toro, North American Properties built Alpharetta’s successful Avalon. Closer to Midtown, NAP resuscitated Atlantic Station, flipping it five years after buying it and netting a reported $120 million profit along the way.

Toro knows this intersection well; he and his wife, empty nesters now, live just down 14th, atop the Four Seasons. His proximity to Colony Square has led him to covet it for its possibilities. After all, there’s enough room for 180,000 square feet of retail and restaurant space. “We call Peachtree gap-toothed,” says Toro. “It needs an anchor, and I don’t mean a grocery store anchor or department store anchor. I mean a place where critical mass has been achieved, and traction has been achieved—in a retail space.”

Toro is a fierce evangelist for density and walkability (just glance at any of his 23,000 tweets), but it’s worth noting that his company’s two major projects in metro Atlanta, Atlantic Station and Avalon, both can be reached most efficiently by car. They are also both ground-up endeavors, creating demand and traffic where none before existed. In Colony Square the traffic is already there; the trick is transforming the parcel into something that’s of a piece with Atlanta’s newfound love of retrofitting old buildings (think Ponce City or Krog Street markets) into desirable destinations.

“This is becoming like a journey through time, to learn everybody’s perspective and what Colony Square means to them,” Toro says. “It’s been Band-Aided forever. But this is more than a Band-Aid. This is radical surgery.”

Photograph courtesy of Holder Construction

Midtown Evolution

Atlanta’s signature thoroughfare began as a Creek Indian trail that snaked along a ridgeline to a village called Standing Peachtree. After Atlanta’s founding in 1837 and the Civil War a quarter century later, the virgin forest was cut away, and the area just north of today’s Peachtree and 10th streets became a rowdy bottleneck known as “Tight Squeeze.” Peachtree was a narrow road filled with mud holes, where morphine addicts, freed slaves, and down-and-out Confederate veterans lurked in a ravine, aiming to rob passing coaches and wagons and, in some cases, kill travelers. Thus the old saying: “Getting through there with your life is a tight squeeze.”

Fulton County intervened by partially filling in the ravine and straightening Peachtree in 1887. The district flourished as a tony residential enclave named Blooming Hill, filled with Victorian mansions and magnolias, and later as a destination retail center. The early 1960s brought a freewheeling era of hippies, when Peachtree took on the moniker “the Strip.” In 1962 a reporter with the Sunday Times Observer described Peachtree from 10th to 15th streets as Atlanta’s own Greenwich Village, full of “avant garde citizenry”—and, as others recall, pot smoke. Subsequent white flight to the suburbs and disinvestment in the area triggered store closings, spikes in crime, and a seedy reputation.

Wayne Mock joined the Atlanta Police Department in 1966, fresh off a tour of duty in Vietnam. As a young cop, his beat was Peachtree from 10th to 14th streets. In a typical night, he’d make five drug arrests. Many of the Victorian homes had been carved into boarding houses with a single bathroom serving several units per floor. Empty buildings and XXX theaters lined the unlit streets, which were littered with trash. “I came out of Vietnam, and I felt like this was worse than combat,” says Mock. “Handguns were rampant. Homicide was rampant. Pedestrian robberies were rampant.”

Six miles north in Buckhead, a young real estate developer named Jim Cushman, along with his mentor Ward Wight, had just completed Paces Place, one of Atlanta’s first condominium projects. The same year that Mock joined the APD, Cushman capped off Buckhead’s first high-rise, the original Lenox Towers. A gregarious Southern gentleman and born salesman, Cushman had been raised in tiny Chester, South Carolina, where he operated a small dairy delivery business. When he was just 22, he was appointed director of the South Carolina Dairy Commission—the youngest person to ever head an agency in that state. In 1962 Cushman sold the dairy business, ultimately heading southwest to growing Atlanta.

After the Buckhead projects, Cushman turned his attention to downtrodden Midtown. With its proximity to Piedmont Park and the Ansley Park neighborhood, Cushman considered the intersection of Peachtree and 14th streets “magical,” often asking himself, as his son Jimmy Cushman Jr. recalls: Why is it dangerous? Why aren’t companies here? Why aren’t people dining here? Why aren’t people walking around?

With Wight’s blessing, Cushman broke away to assemble a team and financial backing to build his Midtown micropolis, a sort of multifaceted small town within the city that would inject energy and a sense of community. Unlike his contemporaries, Cushman had no interest in building office parks along expressways; his goal was to create something special the city could be proud of, something in the vein of bustling live-work-play environments he’d visited and studied. He would stake his reputation and much of his own money in trying to bring this all-inclusive utopia of offices, hotel rooms, condos, and more social attractions to fruition.

Photograph courtesy of Holder Construction

A colony arises

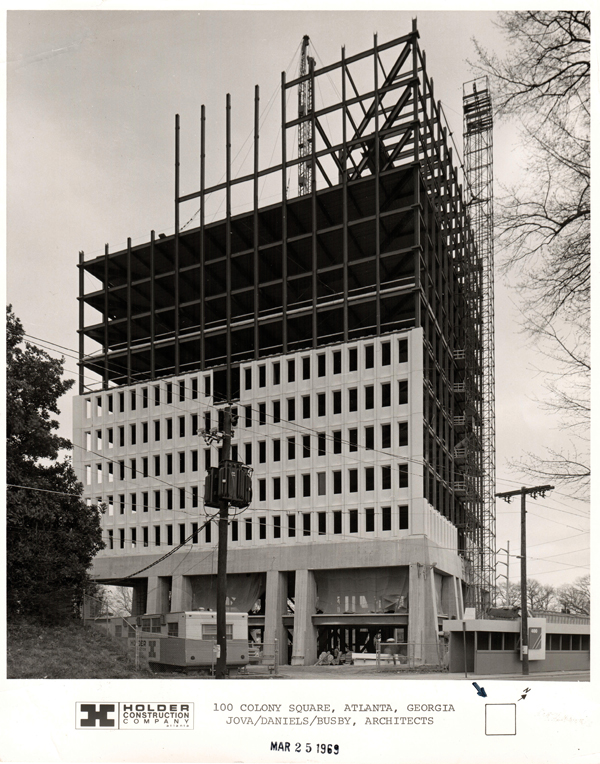

Cushman Corp. announced plans in 1967 for a posh mix of retail, hotel, office, and residential spaces on 12 acres at the northeast corner of Peachtree and 14th. The land, which Cushman had assembled for $4 million, was home to two low-slung office buildings and a 1904 mansion that had once belonged to Atlanta’s prominent Murphy family; they had earned their fortune in banking and sold the home in the 1940s, when it was carved up into offices. Cushman brought on the fledgling architectural firm Jova/Daniels/Busby. He told its lead architect—Henri Jova, the designer of later landmarks such as the Carter Center and Library and some of Atlanta’s first modern homes—the concept was new to the South but viable. Cushman hired Stuart Alston as Colony Square’s first leasing representative. Alston carried a stack of brochures to convince prospective tenants that scooping up rare Class-A office space in Midtown was a unique opportunity. Prospective lenders weren’t so easily won over. No lender in Atlanta could provide the capital Cushman sought, so he made 13 trips north. He finally scored a $10 million loan from two New England banks for the first building, 100 Colony Square, which broke ground on the Fourth of July in 1968. It wrapped the next year and gave Midtown its first trophy building, a 24-story island in a low-rise sea.

A recession slowed progress, but the milestones kept coming: A second, slightly shorter tower opened in summer 1973, and Alston steadily filled the floors with tech workers, ad agencies, and media outlets. The first residential component, Colony House Apartments—a stair-stepped concrete building inspired by Le Corbusier—welcomed its first residents in 1974. In a move that would make modern-day Midtowners cheer, Cushman dug deep to hide a 2,000-space parking garage underground. Less to Cushman’s liking, according to his son Jimmy, was the inward-facing aspect of Colony Square’s buildings, which functioned to channel visitors and residents inside as a layer of safety from the still-dicey street.

“Dad did not want that,” Jimmy says of his father, who died last year at age 84. “But sometimes market forces are there.” The second round of financing, $43.5 million, came from Chase Manhattan Mortgage and Realty Investors. “Money had never flowed that way into Atlanta,” recalls George S. Hart, whom Cushman had brought in to handle project finances.

Backed by a third loan from Prudential, the indoor mall opened in 1973, complete with a large skating rink called Colony Square Ice Capades Chalet, inspired by Cushman’s trips to Houston’s Galleria. A Rich’s department store and a Neiman Marcus would follow. With the opening of the Hanover House Condominiums and Fairmont Colony Square Hotel in 1974, after six years and $100 million, Colony Square was finished.

Photograph courtesy of Holder Construction

Its final tally: three 14-story residential buildings, two office towers, the 27-story hotel, and a retail mall. Cushman moved his family into Colony House, befriending everyone from janitors to tenants. His vision had become his family’s backyard. His son recalls being warned to steer clear of the open drug markets in Piedmont Park. “Mother and Dad had a third child,” Jimmy jokes. “It was my sister and myself and Colony Square.”

Office occupancy crested above 90 percent around 1975, but the continuing recession forced Cushman to file for bankruptcy protection, and the project’s lead creditor, Prudential, took over management in 1975. A decade of legal disputes ensued.

Despite the ugliness, Colony Square managed to become a beacon for New Urbanism. “It really established how this whole area [of Midtown] developed,” says Jack Pyburn, a principal with Lord Aeck Sargent architects who’s owned a Colony Square condo since the 1980s and is considered the resident historian. “It is the core, the anchor of the whole thing.”

By 1986 Midtown’s office market was surging, with under-construction skyscrapers such as the 50-story IBM Tower (now One Atlantic Center) and Colony Square’s neighbor, the Campanile, nearly doubling Midtown’s office space to 5 million square feet. Suddenly the neighborhood was “a developer’s Wild Wild West,” as the Atlanta Journal-Constitution later declared. Meanwhile Colony Square underwent a $10 million refurbishing that adorned the property with polished Italian marble columns and granite floors. A block away, the High Museum of Art had opened beside the Woodruff Arts Center, home of the Alliance Theatre and Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. But despite the upswing in investment and beautification efforts, Midtown remained pockmarked with vacant storefronts and surface parking lots.

In 2000 came the Midtown Improvement District, which collected millions from an extra tax, putting the money toward sidewalks, trees, and extra crime prevention. It wasn’t long before hundreds of condos were rising in glassy towers such as Metropolis at Peachtree and Eighth streets and the curvy 1010 Midtown, which overlooks the old Tight Squeeze gantlet. In 2008 Cushman attended the rechristening of Colony Square’s hotel as the ultra-swank W Atlanta–Midtown, saying the area “far exceeds my dreams.”

But then came another recession. Toro would take customary walks around the neighborhood with Kevin Green, then the newly installed CEO and president of the Midtown Alliance. They saw a district that wasn’t dead so much as slumbering. “We knew it would happen,” says Green. “It was just a question of when things were going to crank back up.”

Photograph by Jeff Herr

Here and now

Over the years Colony Square has traded hands five times. When NAP bought it from global real estate group Tishman Speyer, Toro and company immediately shut down a few “substandard providers”—a salon, barbershop, and health club among them—echoing their strategy at Atlantic Station. This left about 175,000 square feet of retail in an interior mall where the Muzak mingles with smells from Moe’s, Tin Drum, and Chick-fil-A. Elsewhere, between empty storefronts, you’ll find jewelry repair kiosks, a gift shop that resembles the inside of a gas station, a dry-cleaning business. For nearby office workers, its utilitarian value is obvious, but nobody would describe this as a memorable shopping experience.

These days more than 11,000 people work at the intersection of Peachtree and 14th, and six times that many are within a seven-minute walk—i.e., the “walkshed.” More than $3 billion of new private investment is under construction or in the pipeline in Midtown, including about 10,000 residential units that will contribute to the largest ever influx of people into the area. Green refers to Colony Square as being “like an old friend” amid all of this.

Toro has a personal connection to the property, too. After graduating from Rutgers University and moving to Atlanta in 1981, one of his first dates with his future wife was at a Colony Square restaurant. And he’s noted that the dimensions of the property’s current food court are uncannily similar to those of one of his favorite destinations, La Plaza de Santa Ana in Madrid. For Toro, this crossroads for Spain’s capital, one of the world’s great public squares, is now a guiding inspiration. That’s not to say the finished product in Midtown will look like an ornate Spanish tourist hub, but NAP’s vision—admittedly vague at this point—calls for abundant patio seating and space for staged events and live music. As with the Madrid plaza, it will be enveloped by a theater (possibly), a hotel, offices, residences, and three levels of parking.

By next spring large-scale demolition should be underway. The goal is to cut the ribbon by July 4, 2018—50 years after Cushman’s groundbreaking. Exactly what will happen between those two goal posts is still being finalized.

Don’t expect changes to the high-rise midcentury architecture, but more inviting storefronts at street level. From 14th Street, near the W’s entrance, a temporary staircase is being constructed that could be replaced by a “monumental stairway that truly invites people up,” Toro says. Shifting to the other side of property, at the hardscape plaza that faces Peachtree, an existing low-rise building set back from the corner of 15th will likely be razed in favor of something that better communicates with the street—via retail and restaurants—and hugs an existing pocket park with High Museum views. New public passageways could lead to the marquee attraction: a bustling square rimmed by a roughly equal mix of retailers and top-shelf restaurants (Ford Fry and Eataly, for instance), with a high-end fitness center (think Equinox), and maybe a boutique theater.

It remains to be settled whether the roof of the food court will be peeled off, but an open-air plaza is what Toro feels is right. In April he assembled an architecture team of Beyer Blinder Belle of New York City—who completed the retail repositioning of Rockefeller Center, Lincoln Center, Grand Central Terminal, and other iconic properties—and Lord Aeck Sargent of Atlanta for local expertise.

Toro envisions Colony Square working in both competition and concert with projects such as the ongoing multitower 12th & Midtown and a planned overhaul of the Campanile building by developer John Dewberry, a former Georgia Tech quarterback who owns 25 prime acres around Midtown. Dewberry’s plans would add six stories to the top of Campanile and a skirt of retail and offices around the inactive bottom. “We view it as a positive,” Toro said of other developments. “A rising tide lifts all boats.”

Cushman’s gamble on the corner of Peachtree and 14th earned him the nickname “Father of Midtown.” His son says he’d be ecstatic to know his original touchstones for the property—people, community, energy—are being adhered to today. And Alston, the leasing rep who once hustled around Midtown pitching the first big idea, agrees.

“Times have changed,” says Alston, “and I’m glad Colony will change with those times.”

This article originally appeared in our June 2016 issue.