Photo illustration by Darren Braun; Kenneth Rogers/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP

Part I

Four Alarms,

May 21, 1917

The horses knew exactly what to do.

When the alarm sounded, they trotted into their metal chutes, waiting side-by-side until their harnesses dropped from above. As the stable door at Engine Company 7 opened, another alarm blared, and the team galloped out.

They couldn’t sustain that speed. It was a hard two-mile run over rough pavement from the station house on Whitehall Street downtown to the colossal Atlanta Warehouse Company in what is now Adair Park. Spread over 40 acres, the concrete storage buildings were touted as Atlanta’s largest fireproof structures. Inside, though, they held highly flammable bales of cotton and “linters,” silky strands of cotton separated after a first pass through the gin. On this breezy spring day, sparks from a steam shovel ignited the bales.

Horses panting, Engine Company 7 reached the warehouse after motorized crews from two other fire stations. Hose and pump teams saturated what they could while other firefighters closed off sections of the warehouse to contain the blaze. It wasn’t easy; the behemoth complex was virtually windowless, making it almost impossible for firefighters to direct water at the burning bales. In less than two hours, flames consumed all 49 bales of linters along with 170 bales—85,000 pounds—of cotton.

The warehouse blaze was only the beginning. Within an hour Atlanta’s meager fire department was dispatched to three other significant conflagrations, the last—and largest—of which swept through thousands of wooden shanties and Victorian mansions in the Fourth Ward. By nightfall, 10,000 Atlantans were left homeless by the Great Fire of 1917, which destroyed more of the city than General William T. Sherman had during the closing days of the Civil War 50 years earlier.

Steve B. Campbell Atlanta Fire Department Photographs, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center

While cotton burned at the Warehouse Company, a quarter mile to the west, two boys looking for mischief dragged a garbage container behind the home of neighbor Fred Walker and set it alight. Breezes fanned the flaming trash pile, and smoldering scraps slipped into the crawlspace of Walker’s house, igniting its wooden floor joists.

The children tried in vain to put out the fire with a garden hose. By the time a West End neighbor called the fire department, flames were consuming Walker’s two-story home.

With nearby engine companies working the warehouse blaze, headquarters dispatched a horse team from Fire Station 5, a mile and a half away—a mile farther than most horses were conditioned to pull a fire wagon.

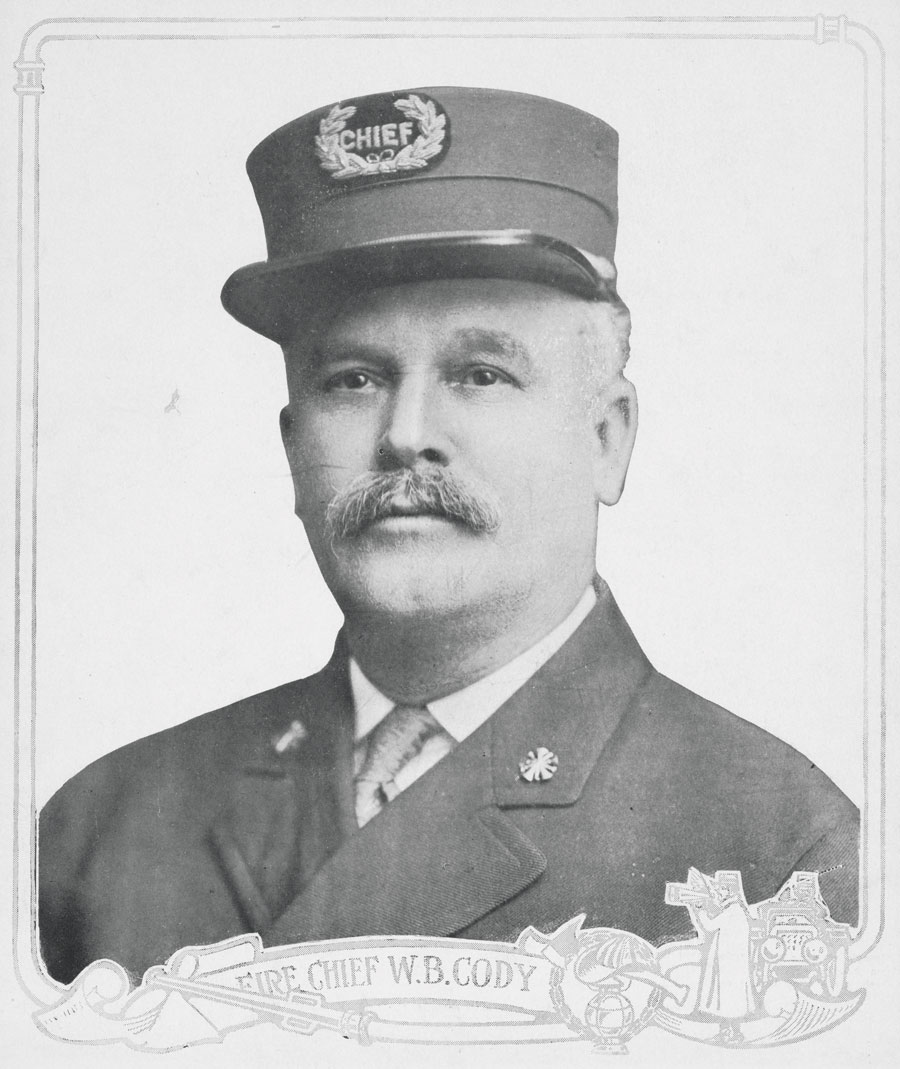

Also en route: Fire Chief William B. Cody, who had joined Atlanta’s volunteer fire department as a driver in 1878, a few days shy of his 20th birthday. Now almost 59, he still liked to get to the front of the action. Cody had spent much of his career working with the department’s horses, so when he arrived at the scene, he realized it would not be possible to bring in horse-drawn equipment to the West End. He called headquarters to request motorized crews as backup, leaving the horse-drawn teams at the stations.

By now the flames from Walker’s house had ignited homes on either side, lofting sparks to nearby streets. Panicked calls flooded fire headquarters. Reinforcements scrambled to douse buildings and create a “firebreak”—a barrier of space or moisture to stop flames from spreading. They drenched Gordon Street Presbyterian Church and the storefronts at the intersection of Gordon and Lee streets.

[ful0357] Vanishing Georgia Collection, Georgia Division of Archives and History, Office of Secretary of State. Steve B. Campbell Atlanta Fire Department Photographs, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center

“There’s a big fire on,” headquarters staff told driver Hugh McDonald when he and members of Engine Company 6 pulled in to replenish the hose on their truck after battling the warehouse blaze. McDonald was sent right back out; a third alarm had been called in at 12:15 p.m. from Washington-Rawson, a working-class neighborhood just south of downtown. An accidental fire had started in the home of W.H. Timms at 355 Woodward Avenue and was spreading through the close-built wooden homes on his block. It had not rained for weeks in Atlanta, and the wood-shingled houses were as dry as kindling.

McDonald and his crew arrived to witness Chief Cody, who had hurried over from the West End, watching helplessly while flames ate through poles supporting streetcar wires along Woodward Avenue. Collapsed wires seemed to writhe in the street and set the fire hose itself aflame.

As Cody, McDonald, and other firefighters waited for Georgia Power technicians to cut the wires, more crews arrived. The horses drawing their engines had traveled so far and at such speeds that their hoofs bled. Now gusting at 15 miles per hour, the wind tossed smoldering chunks of wooden roof shingles through the air like seeds being blown from a dandelion, planting fires that burned two dozen homes in Washington-Rawson and eventually ignited a blaze worse than any seen for generations.

You couldn’t say Atlanta had not been warned.

In 1909 the National Board of Fire Underwriters issued a report noting that wood-frame homes crammed on city lots put Atlanta at a “high conflagration hazard.” Five years later, its 1914 report cautioned that the commonly used wooden roofing shingles prompted the risk of “flying brand fires to a pronounced degree.” In 1916 city lawmakers passed a code mandating fire-resistant roofing (such as asbestos or asphalt tiles) to replace wooden shingles. The ordinance had been slated to go into effect January 1917, but thanks to aggressive lobbying by Atlanta lumber merchants, the city postponed enforcement until July.

The Board also had cautioned Atlanta officials about the risks of scrimping on staff and equipment. Atlanta was one of the least modernized fire departments in the country. Chief Cody commanded a fleet that relied heavily on horse-drawn equipment. Even the city’s hydrants were outmoded, requiring special wrenches to open and shut, and with fittings that were incompatible with modern hoses.

Cody watched crews struggling to contain the Washington-Rawson fire. Then he looked over the railroad tracks and saw yet another plume of smoke rise from Decatur and Fort streets.

National Board of Fire Underwriters Report on the Atlanta Conflagration of May 21, 1917, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center

The flames came from a Decatur Street storage shed for Grady Hospital. Lieutenant J.A. Hooks and members of horse-drawn Ladder Company 12, en route to the main fire station, spotted a pile of cotton mattresses blazing on the facility’s porch, likely ignited by flying embers from the Washington-Rawson fire. Before long, the whole building was in flames. The firefighters had a pump, but lacking hoses—the central station had already distributed every last one—there was no way to get the water to the fire.

Hooks called headquarters for help but couldn’t get through. He wasn’t the only one. So many calls came in that the lines couldn’t handle them, and every public fire alarm had been pulled, crashing the system. Atlantans who weren’t calling the fire department were calling each other to pass along rumors that the blazes were the work of German spies. The U.S. had entered World War I just one month earlier, and Atlanta would play a pivotal role in the war effort, with officers training at Fort McPherson and troops arriving at the new Camp Gordon training grounds.

It was 1 p.m. before other trucks carrying hoses arrived at Decatur Street and tried to soak wooden homes in the alley behind the storage shed. But the advancing wall of fire was so ferocious they had to retreat.

Along Decatur Street, men climbed onto roofs and poured buckets of water over wooden shingles, hoping to stop the fire’s spread. They doused homes with garden hoses. But once fire took hold in one of the wooden shacks, it roared through rapidly. Homes burned to the ground in minutes.

People, horses, and cars crowded into the street. Some fled burning homes and businesses, others rubbernecked at the destruction. Orderlies at Fairhaven Hospital hauled out invalids in their beds, leaving them to wait as ambulances struggled to weave through the crowds.

Just before 2 p.m., less than three hours after the first fire was reported, Chief Cody ordered every one of his 204 firefighters on duty. Then he called Mayor Asa

Candler with another request: Call every city in a 350-mile radius—yes, as far away as Chattanooga and Savannah—and ask if they can help. Forget about the three earlier fires of the day; this fourth one is going to destroy Atlanta.

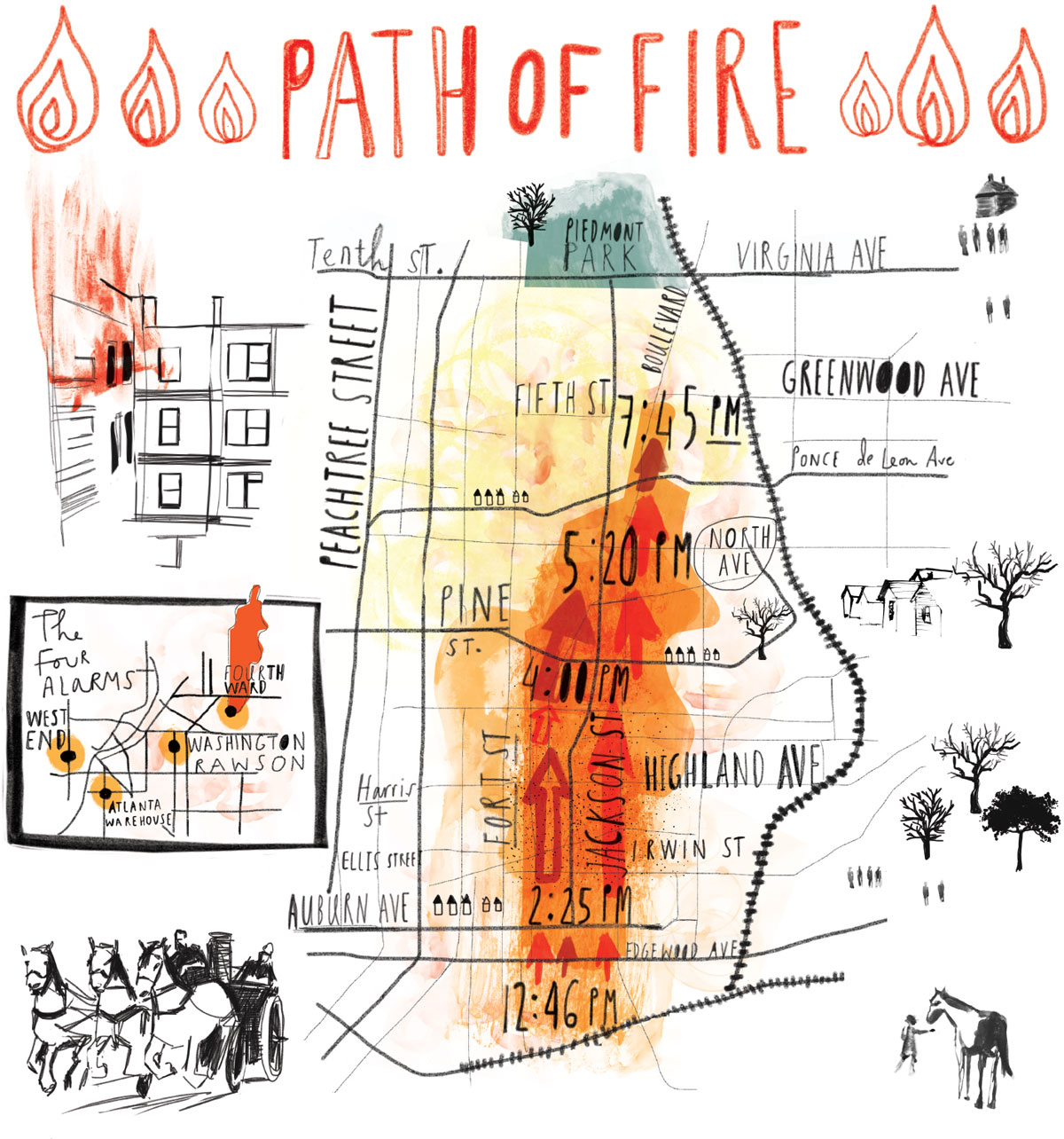

Map by James P. Burns

11:39 a.m.

Alarm: Atlanta Warehouse Company

11:43 a.m.

Alarm: West End

12:15 p.m.

Alarm: Washington-Rawson

12:46 p.m.

Alarm: Decatur and Fort streets in the Fourth Ward

1:00 p.m.

Crews arrive at the fire in the Fourth Ward, but are unable to contain it.

1:15 p.m.

As additional companies arrive, the fire spreads north of Decatur Street and along Edgewood Avenue.

1:45 p.m.

Small fires ignited by flying shingles converge into a wall of flame. Firefighters hope that an empty lot will serve as a firebreak, but winds carry burning embers.

2:25 p.m.

Wheat Street Baptist Church burns, soon followed by St. Paul’s Episcopal. Before 4 p.m., flames destroy Jackson Avenue Baptist, Grace Methodist, and Westminster Presbyterian churches.

4:00 p.m.

Colonel Charles Noyes, Chief Cody, and Mayor Candler make the decision to dynamite large homes to create a firebreak.

4:30 p.m.

Soldiers and officer trainees from Fort McPherson set up a command post at Peachtree and Baker streets.

4:50 p.m.

Martial law is declared.

5:20 p.m.

Dynamiting begins on houses around North Avenue.

6:00 p.m.

Fire reaches Ponce de Leon Avenue, and winds carry burning chunks of wood across the wide street. Military bucket brigades work to dampen homes in the fire’s path.

7:00 p.m.

The wind changes direction and begins to blow the fire back toward the already burned area.

7:45 p.m.

Fire reaches Greenwood Avenue but does not spread farther.

8 – 9 p.m.

Fire crews arrive from Gainesville, Rome, and Chattanooga. Although the fire has been contained, the two-mile swath continues to smolder.

10:40 p.m.

The fire officially is extinguished, but pop-up fires continue for three weeks.

Steve B. Campbell Atlanta Fire Department Photographs, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center

Part II

Exodus from the Fourth Ward

A decade earlier, Decatur Street was known as Atlanta’s den of iniquity. Crammed with shanties and saloons—many of them selling corn whiskey, running gambling operations, or operating illicit brothels—it was reviled by white politicians and pundits. A September 1906 Atlanta Journal editorial characterized the businesses along its thoroughfare as “disguised dives of the worst class” that “fostered and engendered criminals of the lowest species.” It met equal disdain from black middle-class moralists. A writer in The Voice of the Negro described Decatur Street as a hotbed of “staggering men and swaggering, brazen women . . . people divested of all shame and remorse.”

The city’s passage of prohibition in 1907 and ongoing police sweeps had dampened some of Decatur Street’s lively character, but it remained choked with wooden shanties and wagon lots. Respectability increased with each block north of the railroad track: Edgewood Avenue with its brick office buildings; Auburn Avenue, the heart of Atlanta’s black middle class; and Irwin Street, the de facto barrier between the Fourth Ward’s white and black residents.

As the May breeze grew in strength, it blew nuggets of flaming roof shingles northward, some traveling four and five blocks. Now a thousand feet long, the Great Fire rolled along Edgewood Avenue to Auburn Avenue, engulfing a complicated urban geography segmented along lines of race and class.

For black residents, the Fourth Ward was the area they had retreated to after white violence during the city’s 1906 race riot that left at least two-dozen African Americans dead. It was where they saw working- and middle-class stability, symbolized in structures such as the Rucker Building, which housed black dentists, doctors, and other professionals, and institutions such as Wheat Street and Ebenezer Baptist churches. For white Atlantans, it was a rolling terrain close to downtown that offered space to build large homes along Jackson Street and Boulevard, Atlanta’s wide, tree-lined thoroughfare.

Now the wall of flame threatened everyone.

“The last day has come; this fire brings the prophesies of the Bible,” an old woman shouted as flames moved down Auburn Avenue toward Wheat Street Baptist. A few people knelt with her in front of the church while other bystanders stood and wept.

By 2:25 p.m. Wheat Street Baptist had burned to the ground. A half hour later, Grace Methodist Church at the corner of Boulevard and Highland Avenue was aflame. There would be little divine intervention. Jackson Street Baptist was gutted before 5 p.m.

Residents of the Fourth Ward hauled chairs, pianos, trunks, and tables into the streets, calling friends and relatives for help transporting their possessions to safety. But those treasured items acted only as fuel, sustaining the fire as it headed north toward the grander homes on Boulevard and Jackson Street.

It crossed Edgewood Avenue and headed toward a vacant lot. “This could save us,” Cody said, surmising that the big clearing could create a firebreak. But the wind was now 17 miles per hour, strong enough to bend young trees, and propelled the flames northward across the lot.

After lunching with his wife, Pearl, and infant son, Billie, at his home on Boulevard Terrace, law clerk William Hartsfield caught the streetcar to his office downtown. Dense smoke clogged the sky. Hartsfield and his colleagues climbed onto their building’s roof, where they could see flames licking rooftops in Washington-Rawson. Hartsfield noticed that sparks now were shooting through the smoky sky and landing in the direction of Jackson Street, just a block or two from his house.

He rushed back home, where he saw flames moving up Jackson Street “as fast as a man could walk” and neighbors hauling belongings out to the street. “Confusion reigned supreme,” he wrote in a letter to friends the next morning. “Just imagine the terror and helplessness of those people.”

Hartsfield helped Pearl pack a trunk. When flames and smoke approached outside, he urged Pearl to take Billie and their maid and head out the back door, toward a patch of woods two blocks away, near Glen Iris Drive and Ponce de Leon Avenue.

He dragged Billie’s new crib—white enamel, filled with the baby’s clothes and bedding—out back and knocked down a fence to stash it in an empty lot behind his house. He helped his widowed neighbor haul out a trunk. Then, as flames came around the corner of Boulevard Terrace, Hartsfield dragged his own loaded trunk two full blocks to the Ponce de Leon Woods.

[ful0357] Vanishing Georgia Collection, Georgia Division of Archives and History, Office of Secretary of State. Steve B. Campbell Atlanta Fire Department Photographs, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center

That afternoon Colonel Charles Noyes led 2,000 troops in a march from the 17th U.S. Infantry and Officers Training Camp in Fort McPherson to downtown Atlanta, where they set up command at the corner of Peachtree and Baker streets. Soldiers and officers in training—many still feverish after having typhoid immunizations the day before—manned bucket brigades, helped residents evacuate, and directed traffic. They were joined by Georgia National Guard’s Fifth Regiment and Governor’s Horse Guard units, who had been training near Lakewood.

Reinforcements began to arrive from other cities. Just after 3 p.m. firefighters from Griffin arrived on the Georgia Railroad, bringing 1,000 feet of fire hose and heading to the Fourth Ward. But the desperately needed hose could not be used; its modern couplings didn’t work with Atlanta’s outmoded hydrants.

By now the fires in the West End, Washington-Rawson, and the Atlanta Warehouse Company had been contained, so every one of Atlanta’s 204 firefighters was called to the Fourth Ward.

But still the fire spread.

The only solution, Candler, Cody, and Noyes had concluded, was to create a firebreak so large that the flames couldn’t skip over it. They would have to dynamite large homes on the affluent northern end of the Fourth Ward, whose residents had already fled, to keep the fire from crossing Ponce de Leon Avenue and heading toward Piedmont Park. I’ll get the dynamite myself, volunteered Mayor Candler.

Meanwhile, the inferno consumed everything—even the wooden pavers on the northern stretch of Boulevard. “It looked like the end of the world,” Boulevard resident Annie Mae Lipford would recall. Her family made a hasty escape, the chickens from their yard stuffed into the backseat of the car.

By 4 p.m. the Great Fire had spread almost a mile north of its origin at Decatur Street. The dynamite team decided to destroy homes around the intersection of Boulevard and North Avenue, ahead of the fire’s path. Booms from the explosions echoed through the area, and aftershocks shook nearby houses, shattering windows and cracking plaster walls.

After a home was dynamited, firemen moved in to soak the demolished building. At North Jackson and Ponce de Leon, 10 hose operators worked in tandem, combining forceful streams of water to douse the flattened homes.

But as the fire approached the break, the wind reversed direction. After gusting north all day, it began to move south, fanning back over two miles of smoldering lots that stretched from North Avenue to Decatur Street. Almost everything flammable in its path had already been burned or drenched with water.

By 7:45 p.m. the Great Fire had diminished, petering out where embers had landed at Greenwood Avenue, just a few blocks shy of Piedmont Park. Crews from Atlanta, Rome, and Gainesville worked to control pop-up fires and contain electric lines and streetcar wires.

It was not until 10:40 p.m., 10 hours after the Great Fire began, that Chief Cody declared it was under control.

National Board of Fire Underwriters Report on the Atlanta Conflagration of May 21, 1917, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center.

Part III

Aftermath

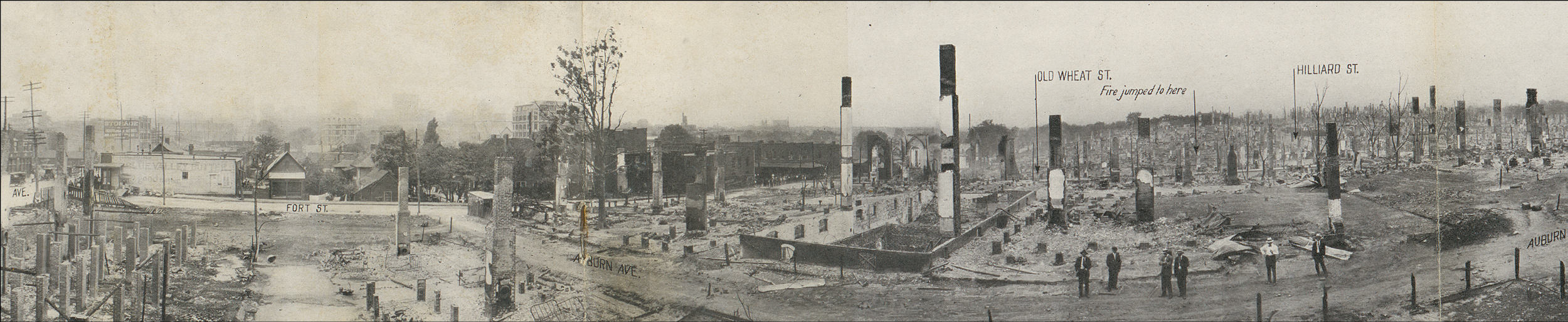

Early Tuesday morning 13-year-old Nina King walked out of the door of her Randolph Street home and entered a foreign landscape. Hundreds of surrounding houses and shops had burned to the ground. All she could see, for “blocks and blocks and blocks,” were chimneys. The skinny stacks stood erect over the vacant landscape like sentries at their posts.

Between the brick chimneys, smoke rose from the debris of obliterated homes. Fires still burned in basements and crawlspaces, fueled by timbers and framing that collapsed inward. For weeks flames would suddenly shoot into the air as gas from damaged lines was ignited by smoldering embers.

William Hartsfield approached the site of his Boulevard Terrace home to find soldiers patrolling the street. Fire had consumed Hartsfield’s house and everything he dragged to the backyard. He gathered the damaged remnants of Billie’s crib, but all that really was saved was what he managed to drag into the Ponce de Leon Woods: a trunk, a few blankets, his cherished phonograph, and a sewing machine.

Hartsfield was stunned to see flames had devoured not only timber houses and dry shingle roofs, but also the large shade trees that lined Boulevard and Jackson. “Every one of them was burned to a stump,” he wrote his friends. “It looked like a desert with exception of the chimneys and here and there a charred stump of a tree together with tangled wires and once in a while a dead cat or dog.”

Hartsfield, who would go on to serve as Atlanta mayor for six terms, told the Atlanta Constitution in an article published on the 40th anniversary of the fire that he still had intense memories—“like a nightmare”—of his experience then. “I realized . . . that when trouble comes singly, there are people and agencies to help us. But when calamity is wholesale, friends and neighbors are too occupied with their own troubles. It’s every man for himself.”

The fire left 10,000 Atlantans homeless. Some, like Hartsfield, found shelter with family. Most were left to fend for themselves in parks, streets, and empty lots.

Miraculously, only one death was attributed to the Great Fire: Mrs. Bessie Hodge of North Boulevard, who reportedly perished from “shock” after being informed that the fire had consumed her home. According to the New York Times, local hospitals took in just 60 patients with fire-related injuries.

“God has been good to us,” Mayor Candler told business leaders who crowded into the Chamber of Commerce on Tuesday morning. “We had a fire yesterday that was not nearly such a calamity as it looked while the fire was burning.”

[dek436-85] Vanishing Georgia Collection, Georgia Division of Archives and History, Office of Secretary of State.

Frederic Paxon, secretary and treasurer of the Davison-Paxon-Stokes department store, was named head of the relief committee. The local leaders vowed to decline outside aid; after all, every city was pitching into the war effort, but Paxon promptly opened the floor for donations to help victims of the fire. Shouts came from every corner of the room.

The first donor was the M. Rich & Brothers department store (a friendly rival of Paxon’s firm) with $500. Pledges came from other stores ($250 each from the J.P. Allen and George Muse clothing companies) and local newspapers ($250 apiece from the Atlanta Journal, Atlanta Georgian, and Atlanta Constitution). Southern Bell and the Georgia Railway & Power Co. each pledged a hefty $2,500 while Coca-Cola contributed $1,000, as did businessman Ernest Woodruff, who two years later would take over the soft drink company.

Black business leaders were not allowed to pledge until all the white donations had been recorded. When they did, it was to “great applause,” noted the Atlanta Journal. Donors included Morris Brown College at $100 and Reverend Henry Hugh Proctor of First Congregational Church at $50. Benjamin Davis, publisher of the influential black weekly the Atlanta Independent, donated $25.

By the time the meeting concluded, the civic leaders had pledged $50,000 for fire victims. (The equivalent of $929,121 in today’s dollars.)

While business leaders met at the Chamber of Commerce offices, another gathering took place at Odd Fellows Hall, the Auburn Avenue home of the African American fraternal organization. There, the city’s black leadership got down to the practical matter of finding refuge for hundreds of misplaced families who would not be taken in by white hotels or churches.

The Odd Fellows building was designated a blacks-only Red Cross station. Its rooftop garden, usually the site of dances and concerts, became a dormitory lined with 200 army cots. The M.D. & H.L. Smith Tent and Awning Company loaned hundreds of cots, as well as a circus tent, which was set up on Auburn Avenue to provide shelter. Cots also lined the basement walls at Big Bethel AME, which had been spared in the blaze.

At the Auditorium-Armory, the Fifth Regiment set up a shelter and field kitchen. On Tuesday they prepared meals—vegetables, ham sandwiches, and slices of cake—for some 2,000 people. In addition to the Armory, shelters opened at North Avenue Presbyterian Church, the Masonic Temple, the Arrarrat Grotto, the Christian Helpers League, and the Marlborough Apartments. The old Woodward lumber factory was jury-rigged as a shelter for 1,000.

All week, horse- and mule-drawn drays and wagons pulled into the alley behind the Armory, laden with furniture and housewares salvaged from the fire zone. Red Cross workers cataloged the goods. It would take weeks for owners to file claims and collect their belongings.

Among the volunteers was a young Margaret Mitchell, who helped to coordinate lost children and wrangle misplaced furniture. “Explosions, fires, soldiers—men, women, and children fleeing from a holocaust—homeless people seeking shelter—every aspect of the disaster found a place in Margaret’s mind and waited there to emerge with remarkable vigor as the refugee passages in Gone with the Wind,” wrote Mitchell biographer Finis Farr.

The fire also separated hundreds of families. Newspapers ran missing persons bulletins. Scanning their morning papers on Tuesday, subscribers of the Atlanta Constitution read notices:

“John Zimmerman, age 12, is in care of Mr. Jones, 196 Oak Street, phone 736. He wishes to find his father, F.C. Zimmerman, or his brother Emmet.”

“John Taylor, at 44 Morgan Street, wishes to hear from his children. There is a boy 7 years old and crippled, a sick boy 2 years old a girl 12 years old and a boy 15 years old.”

“Blanche and Billy Albert: Mrs. J W. Albert is at 84 South Gordon and wants to find you.”

Within days racial tensions at the Armory escalated. In one hall, the Red Cross asked black ministers to man tables where black residents seeking help were asked to go first; they could get assistance only if the ministers vouched for them. No such system was in place for the hundreds of white residents asking for aid.

Sparked by complaints from white Atlantans, the front doors were shut off to black citizens, who were directed to a side entrance used for deliveries. The move incensed Benjamin Davis, publisher of the Atlanta Independent, who days earlier had praised Atlanta’s charitable nature. “When we drive by the Auditorium-Armory and see every front entrance shut tight in the face of the Negroes . . . we are impelled by a sense of righteous indignation to withdraw our commendation and say that the color line is strictly drawn and that the races are being served, rather than humanity,” he wrote. “It seems that our neighbors, in the hour of sore distress and deep sorrow, might spare us in the midst of our tears and our afflictions this humiliation.”

By May 27 Red Cross workers had designated Wednesdays for whites and Thursdays for blacks to appeal for aid. Away from the Armory, the Atlanta Police Department aggressively patrolled the ruined area. Police Chief William Mayo, claiming rampant theft, ordered that “junk dealers and negroes” would be allowed to enter the fire zone only with written permits.

[dek436-85] Vanishing Georgia Collection, Georgia Division of Archives and History, Office of Secretary of State.

Part IV

Rebuilding

Analysis from the National Board of Fire Underwriters conducted after the fire underscored how Atlanta’s lax policies contributed to the devastation: 80 percent of the 1,938 destroyed buildings had shingle roofs, 97 percent were wood frame. In all, the blaze caused some $5.5 million in damage (more than $103 million in today’s dollars). Hit hardest were Atlanta’s African American residents. Disproportionately affected by the fire, they also were more likely than whites to have been denied insurance coverage.

While ruins still smoldered in the Fourth Ward, white residents pushed for ways to leverage the fire to reinforce segregation. On the evening of May 25, white Fourth Ward residents crowded into the North Avenue School to discuss rebuilding plans. They appointed 10 men and 10 women to a commission, and vowed they would not rebuild or sell their properties unless the 20-person team approved the plans. The role of the commission would be, the Constitution reported, “to consider all the needs of the burned area, including segregation of the races, parks, rearrangement and regarding of streets, and building regulations.”

Throughout the summer, the rebuilding committee, City Hall, the Chamber of Commerce, and other groups of wealthy white Atlantans considered a series of presentations and proposals. The one constant: Creating clear, physical barriers to separate the races.

One scheme called for the destroyed area to be remade as a linear greenway, connecting Piedmont Park to Grant Park. Henry Collier, the city’s chief of construction, proposed transforming Hilliard into “Grand Boulevard,” widening the road to 150 feet and extending it up to Ponce de Leon, parallel to the existing stretch of North Boulevard. Grand Boulevard would serve as north-south dividing line, with white people to the east and black people to the west. An extension of Houston Street would create an east-west border that also would serve as a racial barrier.

Other Atlantans called for loftier plans, seizing the opportunity of newly vacant land to rebuild Atlanta along the lines of established cities in Europe or the Northeast. “It would perhaps be impossible for financial reasons to turn the whole burned district into a park,” noted the editors of the Atlantian, a political newsletter, in their July 1917 issue. “But it is entirely possible to make of it a semi-park residential district which will greatly beautify the city.”

Returning to Atlanta in late June from a trip abroad, Joel Hurt, the streetcar magnate and developer of Inman Park and Druid Hills, was dismayed to see “cheap houses” already under construction in the fire zone. That afternoon he dashed off an op-ed to the Atlanta Constitution. He recommended bringing in expert advisers, like the Olmsted Brothers (who had worked on Druid Hills and some of the major properties in Atlanta), asserting, “The expense would be light compared to the value of the advice which would be received.” Hurt also suggested that the Atlanta City Council pass a law halting all rebuilding until a master plan could be developed, pointing out that the fire saved the cash-strapped city millions in demolition and displacement expenses. Just as Napoleon remade Paris to create the Champs Elysees under the guidance of Baron Haussmann, creating the “Queen City of the World,” Atlanta had been presented with a “golden opportunity,” wrote Hurt.

But before May rolled into June, construction began on some of the vacant lots. At the corner of North Jackson and East Avenue, the Knight Apartments were built. At Boulevard and Forrest Avenue, another multiunit building, the Saunders Apartments, rose from the ashes. The apartment buildings weren’t the only radical departure from what had been a residential section known for stately homes; lots once occupied by smaller houses and corner shops now yielded to gas stations and larger stores.

By May 30 Atlanta City Council announced it would enforce the shingle ordinance it had shelved. On May 22, 1918, almost a year to the day after the Great Fire, the city announced that its fire department would be fully motorized. The horses were euthanized or sold at auction.

Rebuilding after the Great Fire did transform the Fourth Ward, but not in accordance with any of the plans proposed in 1917. Unwilling to shoulder the cost of creating parklike developments close to downtown, well-heeled white people simply moved away to Druid Hills or farther up Peachtree Street. Grand homes leveled by dynamite were replaced by apartment buildings. In the center of the Fourth Ward, lots that had housed single-family homes and small businesses became larger commercial sites.

In 1921 Georgia Baptist Hospital relocated from modest space on Luckie Street to a big lot at the corner of East Avenue and Boulevard. In 1925 the Sears Roebuck Co. erected a mammoth showroom and distribution center near the former Ponce de Leon Woods, where William Hartsfield and his neighbors had huddled as their homes burned. In 1929 the Creomulsion Company opened a cough syrup factory at Glen Iris Drive and Forrest Avenue. Atlanta-based Scripto Pen Company built a factory along Houston and Jackson streets.

In the lower Fourth Ward, along Edgewood and Auburn avenues, a black middle class thrived in the face of Jim Crow segregation. Wheat Street Baptist Church, destroyed by the fire, rebuilt with a grand Gothic sanctuary in 1921. Ebenezer Baptist Church, which escaped the fire, grew in influence as pastors Martin Luther King Sr. and Martin Luther King Jr. occupied center stage in the growing civil rights movement. Benjamin Davis and the Odd Fellows faced friendly competition when John Wesley Dobbs and the Prince Hall Masons opened their own building on Auburn Avenue in 1937. The area disparaged for its shanties and saloons became known as Sweet Auburn, the epicenter of black middle-class success.

The heyday did not last. The midcentury victories of the civil rights movement paradoxically contributed to hard times for the Fourth Ward. During the post World War II boom, fueled by cheap suburban housing and expanding highways, middle-class white people moved out to the northern and eastern suburbs. Middle-class black people also moved away: to Collier Heights, the West Side development built by African Americans for African Americans, or to Cascade Heights.

From 22,000 residents in 1960, the Old Fourth Ward’s population dropped to just 6,000 by 1980. More than one-third of those residents lived in one area: the Bedford Pine federally subsidized housing development, formed from a cluster of more than 60 apartment buildings, a few dating back to the post-fire rebuilding efforts.

Once touted as one of Atlanta’s grandest streets, Boulevard became synonymous with intown crime, as did the entire Old Fourth Ward. Indeed, in the early 2000s, as residents and representatives of City Council sat down to craft a master plan for redeveloping the area, many wanted to drop the Old Fourth Ward name altogether and rebrand the district.

But over the past decade, the neighborhood has been rebirthed yet again. In October 2012 the Atlanta BeltLine completed its 2.25-mile Eastside Trail, which begins at Irwin and Krog streets, just a few blocks from the Great Fire’s southern boundary, and ends at Piedmont Park, where hundreds of Atlantans found refuge in a tent city after fire destroyed their homes. The trail has served as an impetus for hundreds of millions of dollars in real estate development and launched dozens of businesses, including the massive loft-office-retail-dining complex Ponce City Market, carved out of the Sears distribution center built at Ponce de Leon Woods.

A century ago the fire presented to Atlanta, in the words of Joel Hurt, a “golden opportunity” to reimagine itself and create the kinds of connected and open spaces that define the world’s great cities: the wide boulevards of Paris, the parks of Chicago, the dense grid of New York. That opportunity was squandered primarily because of prejudice. As development continues in 2017, the challenge will be learning from Atlanta’s past, when rebuilding was driven by, at best, economic expediency and, at worst, racism and classism.

This article originally appeared in our February 2017 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)