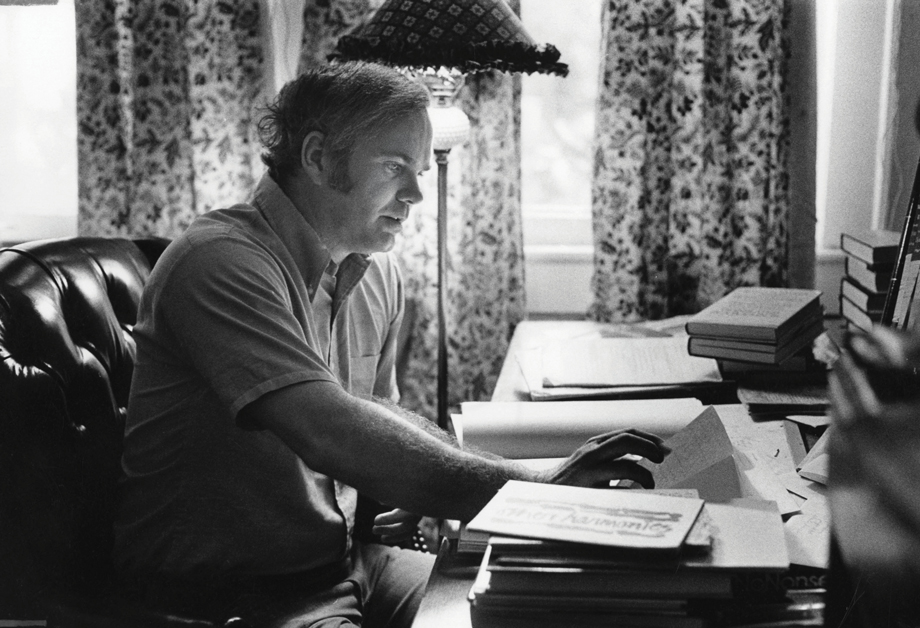

Photograph by Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP Images

I am fuzzy about the time—1985, I believe it was—but we were in the hills of North Carolina, not far from Highlands, and we were sitting outside on a twilight evening that had both summer and autumn in it. Sweet smell of pine forest and honeysuckle, fireflies blinking, song of a nightbird—the sort of setting he might have written about with such exuberance, the words could have posed for a portrait.

We had hiked the hills and had had dinner and were drinking wine fit for the occasion. Good vintage, but not extraordinary. The mood was melancholy, as it always was in the comedown from hours of merriment that marked the energy of those blissfully young days.

That is when he said it: “Boys, they’re about to make me famous, and I don’t know how to handle it.”

The memory is not fuzzy on that.

Pat Conroy said it. He said it to me and to Cliff Graubart and to Bernie Schein and to Frank Smith and to Dan Sklar.

The Boys, we called ourselves, the same simple stamp of comradeship used by millions of men, men grouping up for a poker night, or a game on television, or just a sit-around visit for no purpose other than being together. No rules to being one of The Boys, other than holding true to trust.

And so, there we were on that evening—The Boys, enjoying wine and a melancholy moment, and Pat Conroy announces he is about to become famous.

My memory tells me our response was mostly silence, though there might have been an obscene but gentle put-down about it, for that is the way of language among most men who call themselves The Boys. But if there was anything profound suggested, it was lost in the mood of the evening.

Still, none of us forgot it.

It was not a prediction. It was a proclamation. He was finishing The Prince of Tides, the book that would secure his reputation following the success of The Water Is Wide and The Great Santini and The Lords of Discipline.

Being famous was there for the taking for him, but it was more than a public relations gambit. Fame was in his blood, in his presence, in the enigmatic something that finds nest in select people.

He had a natural onstage presence so huge it overwhelmed his audiences. A large, imposing man, he could enter a crowded room and clear a path with his Irish smile and his Irish blue eyes and his Irish bluster, one of those rare people full up to the brim with charisma.

And he knew how to use it.

Yes.

Everywhere he went—to live or to visit—he had something to say, something to do, something to leave that would be remembered. His presence was more responsible for bringing attention to Atlanta writers in the 1970s and 1980s than anything, or anyone. The publishers of New York paid attention because he talked it up. When he settled in South Carolina, at his home in Fripp Island and, later, in Beaufort, he made the state a center of Southern literature. (I do think his designation as an editor at the University of South Carolina Press was hilarious, however. Pat Conroy, Editor. For anyone who read one of his first-draft manuscripts, it is the definition of an oxymoron. I would have enjoyed seeing Nan Talese’s expression when she first saw the line, Nan having been his longtime editor at Doubleday.)

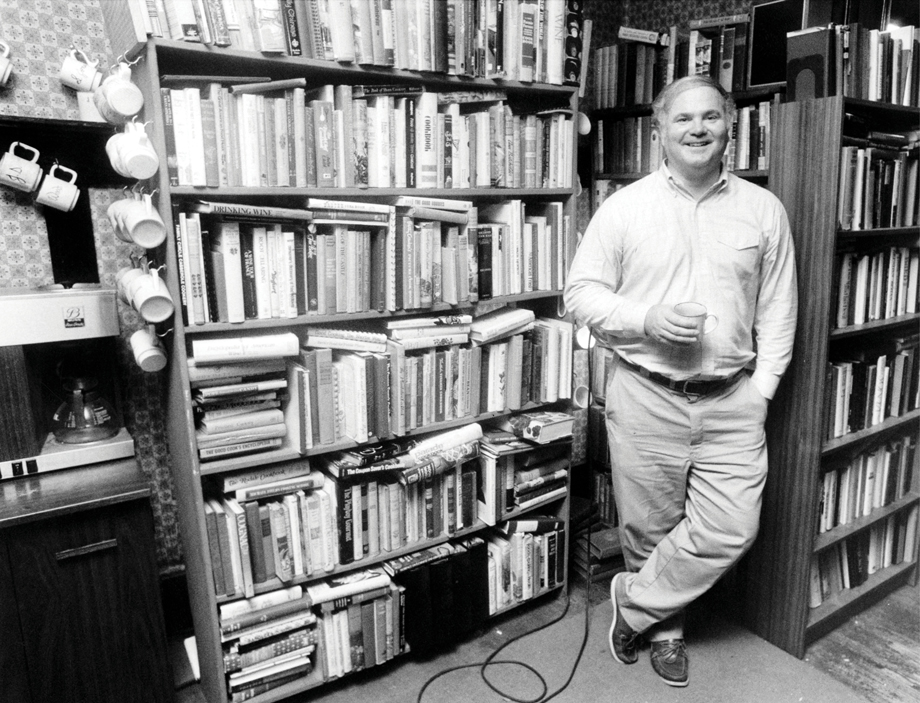

Photograph courtesy of Terry Kay

We met in the spring of 1973 at a luncheon that had something to do with Jim Townsend, then editor of Georgia Magazine. Jim had commissioned me to do a piece on the filming of Pat’s The Water Is Wide, which was in production on St. Simons Island under the title Conrack.

We would spend some time at St. Simons, Pat told me. Talking, he said. He wanted to ask about my experiences as a film and theater writer for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. It all sounded interesting to him, he vowed. Seeing all those movies and plays, mingling with celebrities.

That was the beginning of the relationship. Pat had moved to Atlanta earlier in the year to make a place for himself as a writer, and after St. Simons, there would be get-togethers at the Old New York Book Shop and impromptu drop-ins at his home on Briarcliff Road. A small core of writers grew out of the gatherings—nothing official, just friends. We had a lot in common. Youth. Energy. Promise.

And we had Pat. He was the catalyst.

In the 43 years between 1973 and attending his funeral on March 8, 2016, a lot happened between us, especially in the first 20 years.

We discovered we were cousins through the Peek bloodline.

“Distant,” I would explain.

“Remote,” he would counter.

The oft-told story of his influence on my career as a writer of fiction was true. He did make a phone call to Anne Barrett of Houghton Mifflin, telling her he had read 150 pages of a manuscript that his friend Terry Kay was working on, urging her to have a look at it.

It was a grand lie. I had never written a sentence of true fiction. When the letter came from Anne Barrett asking for the pages Pat had raved about, I went to his house to confront him. I snapped at him, cursed him, told him I had no desire to write fiction and I would be grateful if he would drop the issue. He listened to the ranting, then advised that I had two choices: I could tell Anne the truth, that I had nothing to share, or I could write 150 pages.

I wrote the 150 pages in one month. Out of it came my first novel.

He knew what I would do because he knew I had been reared in a family with a work ethic that said this: If someone has faith in you, you have an obligation to try.

Pat had faith.

And there was the other call.

It was in the early 1990s. He was living in San Francisco and had received news that I was suffering from depression following publication of my novel, To Dance with the White Dog. It should have been the grandest of times for me. Reviews were good. There was interest in foreign sales. A movie was in the planning. The hoopla of it all was like theme music. Still, I was depressed. When Pat learned of it, he began to call with regularity, asking each time about my writing. Each time, I lied, telling him it was going well. Then, one day, he said, “Why are you lying to me? You’re not writing anything.”

I began weeping, the kind of weeping made of desperation and self-pity.

I had nothing to write, I told him. Nothing. When I paused, he said to me, “Kay, you’ve bored us for years about your miserable life in the Catskills, but you’ve never written a word about it, so here’s your story: Young plowboy from a Georgia farm ties his mules to a fence post, packs his meager belongings in a pillowcase, stuffs what few dollars he has into the toe of a sock, and boards the Greyhound bus going north. He runs out of ticket money in the Catskills, takes a job as a busboy in a Jewish resort, and falls in love with a beautiful Jewish girl who’s a guest in the hotel.”

I laughed. I knew Pat. Knew he was being deliberately absurd in an effort to change my mood. I said, “Conroy, that might be the silliest plotline I’ve ever heard.”

There was a pause, a silence stretching from San Francisco to Atlanta, and then he said, “You didn’t read The Prince of Tides, did you?”

I thought: My God. That’s exactly what he did. Dumb Southern coach/teacher makes his way to New York to rescue his fragile sister and there meets the Jewish psychiatrist, Lowenstein, love of his life.

And then I thought: If he can get by with that, so can I.

Shadow Song came out of it. Shadow Song built the house I live in.

The phone call that led to Shadow Song also revealed something to me about Pat I had not realized—his need to be heroic. Thinking of him now, in the freedom of imagination, I believe as the first child in the combative family of Don and Peggy Conroy, he must have pinned a bath towel around his neck and set out in make-believe to save the world—first the one of his family, and second the one called Earth.

His father, Don—the Great Santini—once described to an interviewer that Pat was always the hero in his stories, and because heroes required villains, he, Don, had served that role for his son, which was why there were so many references about the contentious father-son relationship in the Santini stories. There are those who would question Don’s take on it, for he was as prone to exaggeration as Pat, and I always believed he had a myopic view of his place in his son’s angst. There were many things that angered Pat other than his father’s temper.

Still, Don was not wrong about Pat’s wish to be heroic. In his writing, the Pat characters—the protagonists—are always valiant. Gloriously so. They encounter threat, meanness, injustice, misery, and they metaphorically leap tall buildings and throw their bodies on nuclear warheads, and in the end, the world is saved and they stand triumphant—especially in the imagination of the reader. It is precisely that quality that has endeared him to millions, especially those who subconsciously wish to be rescued from some dastardly wrongdoing in the dysfunctional world of their existence.

Pat, the hero, is near-operatic in each of his novels, but for me, his best writing was in his essays and especially in his letters of anger and protest against such issues as censorship and inept education. In those explosions of righteousness, the language is riveting because he was far more effective at the short, intense expression than in his long passages of singing description, as good as they were.

Then, too, much of his presence was beyond language; it was in the mere force of his name: Pat Conroy. His name peppers the front and back of book jackets of countless writers, writers who took nourishment from his cheerleading endorsements, who memorized his words and slyly dropped them into their conversation. They were his congregants. His name was their blessing, their heroic rescue from doubt, their wished-for passage into literary acceptance. In book festival crowds, they thrashed around him like smiling piranha.

On the day of his funeral, at St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Beaufort, South Carolina, I heard people calling him a complex man.

Unquestionably, he was that. It was part of his ascension to fame.

In the praise heaped upon his memory by mourners who gathered to celebrate his life, he was described as kind and giving and caring. And, yes, that was true. I am a beneficiary of that generosity. Countless others gratefully make the same claim.

Yet there are those who will tell you he could be a bully, a stubborn man with an addiction to being right, a man beset with demons, and a man who could find curious pleasure in unleashing his devastating wit against people who cherished him. I knew that side of him, also. There were a few times when the sting of his surprising, unexpected swipe left scars. He was a master at it, for he leveled it in the disguise of charm and you did not know whether to fight him or to laugh with him. There was no blood, yet you knew you had been wounded. To say he harbored a warped sense of humor is understatement.

“Just Pat,” people would say. “Just Pat.”

Over time, in his odyssey to find a place of adventure—Rome (Italy), Fripp Island, San Francisco—he eased away from early-on friends in Atlanta, though apparently he had been making an effort to reconnect with many of them. There was talk of it in the milling crowd attending his funeral. The mending was a good thing, those reconnected early-on friends admitted, a little like old times.

In fairness, time had a lot to do with the fading of his Atlanta influence, and it wasn’t just Pat’s doing. It was all of us. Anne Rivers Siddons moved to Charleston. I found my way to Athens. Rosemary Daniell relocated to Savannah. Cliff Graubart’s book parties at the Old New York Book Shop—the parties that gave emerging writers an identity—ended. The Boys drifted apart. Frank Smith moved to Maine. Bernie Schein went home to Beaufort. Dan Sklar went north to New York. Others died—Paul Darcy Boles, Paul Hemphill, Bill Diehl, Marshall Frady.

It is the way of life. Change. Slow and swift. People go from improvised dinners of watery oyster stew in chipped coffee cups (as Pat once served) to Champagne in Waterford crystal (as he surely enjoyed). Friends and acquaintances are lost along the way, new friends and acquaintances take their place. Novels are written of such storylines.

In full disclosure—as the newspeople say—I had not been close to Pat for 20 years. He would call occasionally, always with the same blarney he used with many people: “It’s up to me to keep this dying friendship alive.” I enjoyed those calls, but I had long known I was mostly a touchstone to another time for him, a memory residing in his Rolodex, one of the early-on people. Still—and this is honest—I was never bothered by the sense that I had become an outsider in his life. I knew there was more to the calls than periodically touching base. He had either a need to assuage some gnawing sense of obligation, a need to keep up appearances, or a wish to find some comfort in an old moment, perhaps one founded in the North Carolina mountains when not so much was expected of him. To me, it was Pat being Pat. Just Pat. I followed his rise to fame with interest and pride, but I preferred him as one of The Boys, not as a celebrity. Still, the sweet moments were indescribably fine. The last visit was one of those moments.

I saw him on Tuesday, January 26, at Emory University Hospital. He was weak and in some pain, but he was also jovial. We shared a few stories, ragged at the edges from so much telling over so many years. I hugged him. Told him I loved him. I did not believe I would again see him alive. And I didn’t. My last viewing of him was on March 7, in Anderson Funeral Home. In the casket, he did not look famous.

But he was, as he had proclaimed he would be. Death did not rob him of that quest.

Still, getting there was not easy work for him, not with the speeches, the blurbs, the parties, the begging of dreamy writers, the requests for selfies, the never-ending demands of giddy fans. Hard doing, it was, but necessary. As Pat learned, you cannot outrun fame, even if you wanted to. He didn’t want to. He had an ordination to accept it, much like the title of a Robert Frost poem I have long favored: How Hard It Is to Keep from Being King When It’s in You and in the Situation.

It’s a line that fit Pat perfectly.

Photograph by Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP Images

In 2001, his fame riding high, Pat returned to the Citadel, his alma mater, to give the commencement address, ending an estrangement of many years. On that day, he invited Citadel graduates to attend his funeral when the time came. All they had to do to gain entrance was to announce, “I wear the ring,” the opening line to The Lords of Discipline, the book that had caused the rift.

If Pat had shared this plan with The Boys in 1985, in the North Carolina mountains, we would have convulsed in laughter.

But that was before he became famous. Famous people have a pass when it comes to being highly dramatic.

The graduates remembered his invitation, of course, for on March 8, at St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Beaufort, they appeared, forming a long human corridor from the hearse to the church. Inside, an entire section had been reserved for them. When they went forward for communion, I saw several of them weeping as they accepted the wafer.

Too, there was this: The priest called for a statue of Pat to be erected in Beaufort.

If it happens, I hope they make it life-sized from bronze. He should be holding a bronze journal pad in his left hand and the bronze replica of a Montblanc fountain pen in his right hand, for that’s what passersby and fans and wistful writers would want to touch, to rub. For the magic, I mean. With the touching, the rubbing, the bronze will stay bright on the pad and the pen, and that would please Pat.

If it does happen, if a statue is erected, I want to attend the unveiling with The Boys—with Cliff and Frank and Bernie and Dan.

We were there at the beginning. We should see it to the end.

This article originally appeared in our May 2016 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)