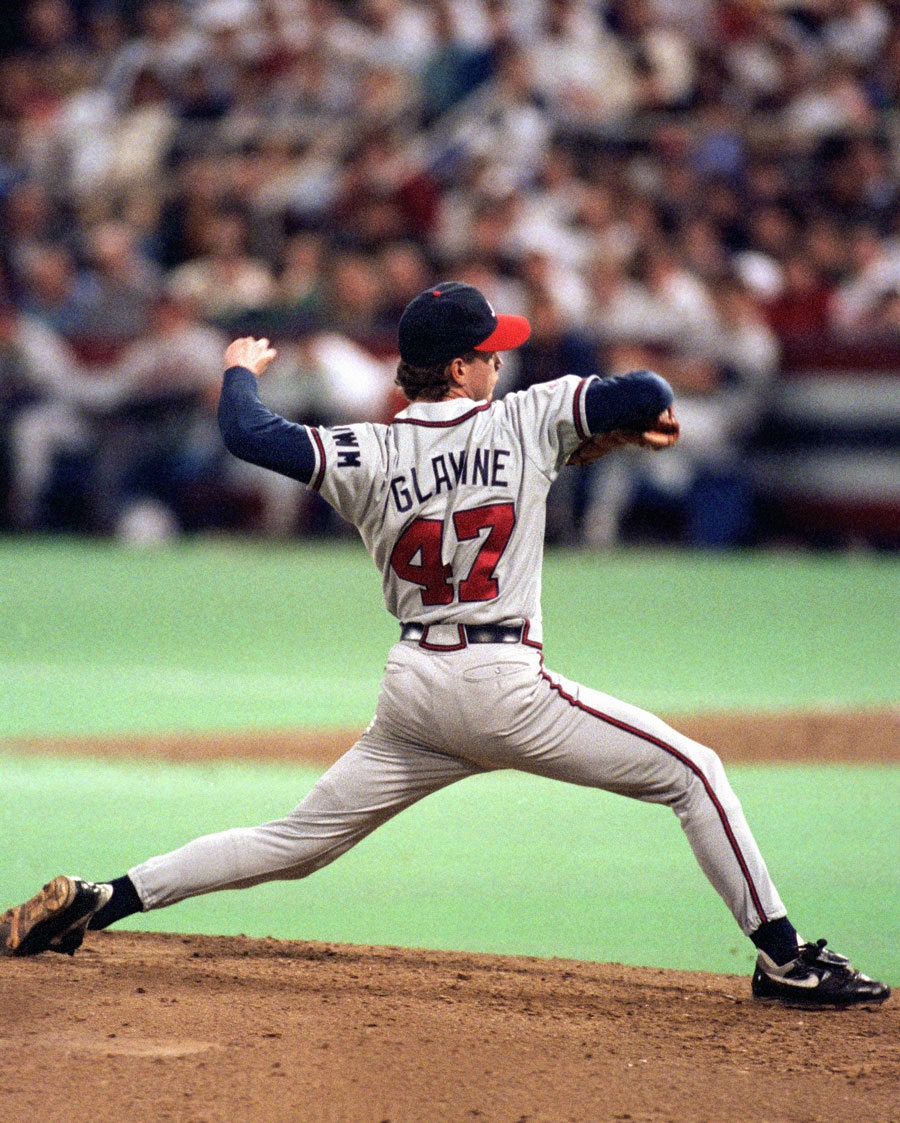

Photograph by Jerry Grillo

As the Atlanta Braves were taking down the Los Angeles Dodgers to win their first pennant in 22 years and set up their World Series showdown with the Houston Astros, I couldn’t help thinking, almost paternally, “I’m so proud of these fellas.” As if I had some kind of stake in their fortune, beyond the usual fan’s irrational proprietary sensibility.

The Braves are led by a bunch of young stars, many of whom weren’t alive when the franchise turned itself around overnight in 1991, the worst-to-first year. Ever since then, for 30 years, the club has been closer to first than worst. And now, 30 years later, history seems to be repeating itself for my family.

This current crop of Braves is very special to us because we’ve enjoyed them long before they were famous, long before most diehard baseball fans had even heard of them. Ozzie Albies, Austin Riley, Adam Duvall, Freddie Freeman, Max Fried, Charlie Morton—before they were household names, they were Gwinnett Braves or Stripers (the AAA Atlanta Braves franchise changed its name in 2018).

And we were lucky enough to see them all in their raw youth, because my family loves minor league baseball. It’s a love affair that goes back to 1985. My wife and I were newlyweds from New York. I was the sports editor of a small newspaper in South Carolina. Down the road apiece lived the Sumter Braves of the old Class A South Atlantic League.

Photograph by Rick Stewart/Getty Images

The Can’t-Miss Kids

Greg Tubbs already knew they were something special, his teammates on the 1985 Sumter club, guys named Tom Glavine, Ron Gant, Mark Lemke, Jeff Blauser. He could see something that I could not, would not for another six years. All I could see was a bunch of 19-year-olds. They seemed like babies, and I was only 23. But Tubbs could see it as clear as a hanging curveball stuck in time.

“These guys were winners, they were going places, and I could clearly see that,” Tubbs recalled recently. He had excellent vision that season when he was 22 and leading the South Atlantic League in hitting with a .356 batting average. “I knew that this was a good group of players—that we were a good group of players. Everyone had a high baseball IQ.”

After 20 years of coaching high school kids, Tubbs thinks a lot about baseball IQ, about instincts. His instincts from 1985 were right on, of course. Six years later the Atlanta Braves stunned everyone, except perhaps Tubbs and a few others, by winning the 1991 National League pennant and losing a work-of-art World Series to the equally surprising Minnesota Twins.

Those Braves featured, among others, a slugging/speedy Gant, gritty infielders Lemke and Blauser, and ace lefty Glavine, Tubbs’s old roommate in Sumter, who won the first of his two Cy Young Awards that year. Glavine, a peach-faced kid from Massachusetts, had a New England accent that found its way into Tubb’s speech.

“I’d call home and, subconsciously, I’d start talking that accent of his, like I was from Boston,” Tubbs said. “My mother would be like, ‘what is wrong with you?’ It was pretty funny. But we were a tight team in Sumter. Even though we were all trying to get to the same place, the major leagues, we didn’t compete against each other. That was a team. We played well together, and went out together after.”

My wife, not quite the baseball fan that I am, would indulge me and watch the postseason games on TV, remarking, “Hey, we saw that Lemke guy when he was an embryo . . . didn’t you get his picture?” And, “is that the same Glavine who looked like he was 12 back in Sumter?”

It thrilled us to see the guys we’d watched take their pro-ball baby steps now playing in the big show. For Tubbs, that 1991 season was probably a little bittersweet. While his old teammates were playing on the biggest stage in sports, he spent the season with the Class AAA Buffalo Bisons, having been traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates (the team Atlanta beat for the pennant in the 1991 playoffs).

And it was kind of a dead end for an outfielder because the parent club in Pittsburgh had all-stars Barry Bonds, Bobby Bonilla, and Andy Van Slyke roaming its pasture. Tubbs, who was elected to the Buffalo Bisons Hall of Fame in 2014, could see this situation clearly, too.

“Buffalo was a great baseball city, with great fans,” he said. “But I knew there wouldn’t be much chance for me to make it into the Pittsburgh outfield.”

Photograph by Elsa/Getty Images

The New Bunch

My son is a non-verbal young man with cerebral palsy. He shares his reactions to thrills not in words, but with sounds and gestures. He’s exercised plenty of those sounds and gestures at Coolray Field, home of the Gwinnett Stripers-formerly-Braves. He’s made those sounds and gestures in response to home runs by the aforementioned Messrs, Duvall, and Riley.

We’ve taken Joe to Coolray Field at least a dozen times, and made the trip up to South Carolina to watch the Greenville Drive play in Fluor Field, which is sort of mini-Fenway Park for this Red Sox minor league club.

But Coolray is our homefield. The ushers act like they know Joe when we arrive, and guide us right to the wheelchair-accessible section along the third-base side. I’ve lost count of the foul balls my son has been handed by ushers, or Batman (Spider-Man, once).

We’ve been—or at least, I’ve been going—since the park opened in 2009. I saw old Charlie Morton pitch there when he was still young. Charlie was injured in Game 1 of this year’s World Series and replaced by Tucker Davidson, most recently of the Stripers. My family watched young Tucker pitch in Coolray in 2019.

Minor league ball is just better for us. Easier to navigate a small, intimate ballpark with my son’s wheelchair; and easier to make a quick exit, when we must. And you can’t beat the entertainment. Forget all the giveaways, and the goofy games on the field—which are all part of the fun, really. But even without that stuff, you’ve got the best show on grass. Baseball, played by people who really want to be there.

We watched Freddie hit balls in the gap, saw Ozzie there, Ronald Acuña, Ian Anderson. Our boys. We saw the Braves’ pennant-winning manager, Brian Snitker, take the long walk to the mound right there in Buford—or is it Lawrenceville? Whatever you call the overbuilt, suburban retail jungle surrounding Coolray Field, once you’re inside the ballpark, everything else falls away, and it’s all about the world of the game. All of that green. The bats, balls, perpendicular lines stretching out, conceivably, forever.

In a minor league park, it’s all right there, close, like in a living room with a grounds crew. As a family, Coolray is where we fell in love with this particular crew of Atlanta Braves. We root unabashedly for them—we don’t do the ridiculous Chop, but we yell like hell. And it’s not just because we’re Braves fans. It’s because these guys feel a little bit like family. It’s a minor league thing.

Tubbs feels it. He was traded away from the Braves a few years after being selected the top player in the entire organization, sent to the Pirates system, then the Reds. If anything, his main allegiance is with the Reds, who gave him his only opportunity to play in the majors, briefly in 1993.

“But we are in Braves country, and I’m rooting for them,” said Tubbs, who now lives in Cookeville, Tennessee, where he’s coached both of his sons. He reckons that he’s coached six or seven young men who have signed pro contracts, including his son Darien, who played in the Los Angeles Dodgers system for a while.

“The Braves gave me an opportunity to play pro ball, and I’ll always be thankful for that,” he said. “I was young, and those were some wonderful years.”

After hanging up with Tubbs, who I hadn’t seen or spoken with since 1985, I considered his long love affair with the game, those joyful salad days with Sumter when he was the best player in the league, best in the entire Atlanta Braves system, rooming with future Hall of Famer Tom Glavine, playing the game with future World Series champions.

I thought of Tubbs in that moment, before 1991 and 2021, before the stupid Chop, thought about how young he was, and how young Glavine was, and all of them, and all of us, gleaming with hope and expectation that felt timeless. These ruminations brought to mind something that the late, great author and former—if briefly—minor league ballplayer Paul Hemphill wrote about playing ball in the so-called bush leagues: “In retrospect, those were the most gloriously giddy days I have ever known.”